Mitey Problems Come in Small Packages

While new research shows promise in helping better control mites, these small parasites continue to infest bee colonies.

Many experts believe mites, particularly the Varroa mite, are primarily responsible for the decline in the number of healthy bee colonies. “A good parasite doesn’t kill its host,” says David Fischer, Bayer CropScience director of pollinator safety and head of the new Bee Care Center in North Carolina’s Research Triangle Park, explaining that the parasite needs its host to survive.

However, the Varroa mite, which originated in Asia and has since spread west, first to Europe and then to the United States in 1987, does not fit the description of a good parasite. Virtually all feral or wild honeybee colonies have been wiped out by these mites, reports David Tarpy, a North Carolina State University Extension apiculturist.

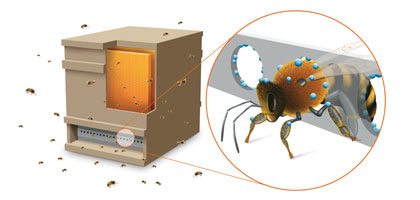

Visible to the eye, the Varroa mite sucks the hemolymph of a bee, weakening its immune system and transmitting diseases. “The Varroa mite is the No. 1 factor affecting bee health,” says Sara Myers, an apiarist and event manager at Bayer’s Bee Care Center in Research Triangle Park. She adds that the Varroa mite is known to transmit more than 20 viruses.

“The Varroa mite is an external parasite that attacks adult bees and the developing honeybee larvae,” Tarpy says. “The adult mites have a flattened oval shape, are reddish-brown in color and are about .06 inches wide — about the size of the head of a pin.”

He says that the mated female enters the cell of a developing bee larva and lays as many as six eggs. The developing mites feed on the bee pupa and, depending on the number of mites, might kill it, cause it to be deformed or, in some cases, have no visible effect. While the male mites die in the cell, Tarpy says the adult daughter mites climb onto an adult worker bee and feed on its hemolymph. The female mite can then repeat the cycle by entering cells of other developing larvae.

Bayer researchers are working to develop new technologies that allow bees to self treat for mites.

Mites prefer drone larvae to worker larvae, Tarpy says, noting that they will infest worker larvae and eventually kill the colony if preventative measures are not taken.

Tarpy says many bee colonies succumb to Varroa mite infestation in the late summer or fall. “It’s difficult to simply inspect a colony and determine if it has a high level of mites,” he says. “Therefore, it’s important to sample beehives to estimate the degree of infestation.”

When inspecting for Varroa mites, Myers says if you have three mites per 100 bees, then you have a problem and need to treat the hive. Myers, who has had to deal first-hand with Varroa mites, says there are two methods of detection if beekeepers suspect a problem — an alcohol wash or a sugar shake.

For the alcohol wash, which Myers says is the more accurate test, collect 100 bees and submerge them in a jar with alcohol. “This will cause the mites to fall off the bees and you can easily count them,” she says. While it’s the more accurate test, the bees tested die during the process.

The sugar shake method does not kill the bees, but it’s also not as accurate. To perform this test, collect 100 bees and put them in a jar of powdered sugar, shaking the jar until the bees are coated in white. This causes the mites to fall off the bees, allowing you to count them.

Once you’ve completed one of these tests, Myers says you’ll know if the hive needs to be treated.

Another mite that is parasitic to honeybees is the trachea mite, which is microscopic and lives in the respiratory system of bees — causing them to suffocate, Fischer says. Introduced in the U.S. around 1985, the trachea mite caused significant damage for several years, but beekeepers have it under control, Fischer reports.

While the trachea mite is not of major concern to beekeepers today, Nosema ceranae is. This gut parasite keeps bees from being able to absorb nutrients from food. Essentially, it’s dysentery in adult honeybees, Myers says, adding that there have been more reported cases of Nosema ceranae in the past five years.

Fischer adds that symptoms are similar to starvation. “Beekeepers will notice that the bees’ food consumption skyrockets, but they aren’t getting the nutrition,” he says. “When you look at the hive and see bee feces, you know its Nosema ceranae.

Proper Care

“It’s not just one thing that impacts the bee population,” Fischer says. “It’s a combination of factors that culminate — parasites, a weakened immune system, diseases, poor nutrition, a harsh winter, etc. Bees are like people; they need food, shelter and water. If they are healthy, they tolerate diseases and parasites much better. It all hinges on nutrition.”

When looking to control mites, Myers says beekeepers must take a comprehensive approach and ask:

• What management techniques am I deploying?

• How many mites do I have?

• What’s the health status of my colonies?

• What are their food sources?

By answering these questions, Myers says beekeepers will know if they need to change their management practices. Plus beekeepers will have an increased awareness of the hive health as they are out working with them, she says.

As the Bee Informed Partnership and the Apiary Inspectors of America survey beekeepers, the number of colony losses reported is decreasing. “We are still not back to normal, but we are at least trending in the right direction,” Fischer says.

He thinks there are two reasons for this trend reversal. The first is an increased awareness of the Varroa mite, resulting in better control. And second is that beekeepers are paying closer attention to bees’ needs during the winter and providing supplemental food.