Wheat accounts for over 20 per cent of all calories consumed in the world. The rising global population is demanding a sustainable and secure source of wheat, pressuring major wheat exporting countries like Canada to be at the cutting edge of varietal development.

Variety development across the world took a major leap forward in early 2016 when, at the annual Plant and Animal Genome Conference, it was announced that a Canadian-led team had sequenced 90 per cent of the highly-complex genome for bread wheat.

This breakthrough in genomic sequencing was accomplished, in part, through the Canadian Triticum Applied Genomics (CTAG2) project, which is co-led by plant scientist Curtis Pozniak of the University of Saskatchewan’s Crop Development Centre.

Wheat researchers across the globe will now have a resource that will allow them to better identify genes responsible for adaptation, pest resistance, stress response and improved yield.

“Think of the sequence as the blueprint,” explains Pozniak. “So now we can see the genes and we can see the genomic structure. What we need to be able to do now is associate each of those genes with phenotypes that are important in the field. That’s really where the hard work begins.”

With the blueprint in place, years earlier than anticipated, researchers and breeders will begin work linking genotype and phenotype. Phenotype is the observable characteristics of the plant that result from the interaction between the genotype and the environment.

Pozniak is quick to emphasize that while sequencing the genome strengthens the foundation of varietal development and provides an important tool for breeders to improve selection efficiency, it is only the first step in a complex process.

“What we’re looking at with any kind of genomic resource is being able to improve the efficiency of selection in the long run,” he says. “If you can identify and understand the package of genes that result in a phenotype that has economic value, then it is quite easy to track in the breeding program as we’re trying to improve other traits such as yield.”

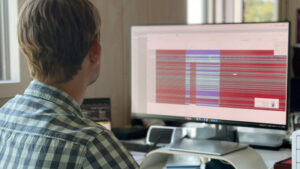

Since the announcement in January, Pozniak and his team of researchers have been working diligently to ensure the entire genome of the test variety, Chinese Spring, is mapped completely and accurately before taking the next step.

“The intent is to release the sequence into the public domain for breeders and researchers to use however they see fit,” he says. “That will happen in the next few weeks and months as we finish up some quality control on the data. We don’t want to release any data that could lead anyone astray. So we’re checking and double-checking that the data is fine and then we will make the data available on a website for anyone to download.”

The CTAG2 project, which includes researchers from the University of Regina, the University of Guelph, the National Research Council and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, received funding from the Saskatchewan Wheat Development Commission, the Alberta Wheat Commission, the Manitoba Wheat and Barley Growers Association, and the Western Grains Research Foundation, along with several other organizations. It is part of a larger collaboration involving researchers in Canada and from across the globe, who have been collaborating as part of the International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium.

Pozniak says the excitement in the international crop research community about the release of the wheat sequence is unmistakable. Wheat researchers are now ready to put this tool to use in breeding varieties that will meet the needs of farmers and end users throughout the world.

“Completing the sequencing really allows us the opportunity to concentrate on how we can use the sequence, especially the biology and breeding behind it. Most of the effort was around generating the sequence and now we’re at the stage where we can actually take it to the field and do biological research on wheat in a way that we haven’t been able to do before.”