Funding cutbacks are causing growing concern among industry stakeholders about the future viability of the National Plant Germplasm System.

The National Plant Germplasm System collects and conserves plant genetic resources, or germplasm, from all over the world. Curators and other scientists acquire, preserve, evaluate and catalogue this germplasm, and associated information, in 20 genebanks across the United States, distributing it to researchers and breeders at no charge and without restrictions. The collection currently contains more than 557,000 samples of more than 14,600 plant species. It annually distributes an average of 200,000 samples to researchers worldwide, about 75 percent domestically and 25 percent internationally. Without it, improvements to varieties and hybrids would be harder to make.

“The seed industry is completely indebted to the NPGS collection to be able to continue to make plant improvements,” says Tim Cupka, an independent corn breeder at AgReliant Genetics and the American Seed Trade Association liaison for the NPGS. “If we don’t have a strong germplasm collection, there really is no opportunity to evaluate it for all the various traits that we have to deal with and try to make selective improvements in our commercial varieties and hybrids, not just here in the United States but globally.”

The NPGS’s origins can be traced back to the late 19th century, but many of its genebanks were established soon after World War II. The NPGS assumed its current form during the late 1980s and is one of the largest national genebank systems in the world. It’s a network of organizations and people that includes universities and NGOs as well as industry stakeholders. The NPGS is led by the Agricultural Research Service—the in-house research agency of the United States Department of Agriculture.

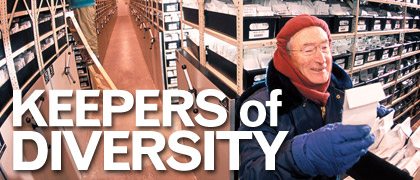

Samples of seeds maintained at the Agricultural Research Service’s National Seed Storage Laboratory in Fort Collins, Colo. |

Support from Partners

The base collection is housed at the National Center for Genetic Resources Preservation in Fort Collins, Colo., which maintains backup seed samples of the germplasm that is held in working collections located across the United States, and which also conducts research on developing more effective germplasm management and preservation methods. Germplasm is kept in both short-term and long-term storage depending on seed characteristics. The NCGRP uses advanced techniques such as cryopreservation—freezing germplasm in or over liquid nitrogen at a temperature of -320.8 F —for long-term storage.

The National Germplasm Resources Laboratory at Beltsville, Md., also supports the system, catalogues all incoming germplasm, and acts as a hub for plant exploration and a clearing house for the exchange of germplasm with foreign countries. It also maintains the Germplasm Resources Information Network, a data management system containing information on all genetic resources within the NPGS.

“The people that run the program for USDA and at our collection centers as well as our [National Center for Genetic Resources Preservation] are excellent partners to our industry and they do a terrific job with the resources that they have,” says American Seed Trade Association president and CEO, Andy LaVigne. “They realize this truly is the foundation of America’s agricultural community, and we couldn’t ask for a stronger group of people than we have today.”

Tomorrow’s Challenges

The NPGS faces a number of challenges, not least of which is managing and expanding operational capacity and infrastructure in the face of diminishing budgets. The USDA/ARS provides around 80 percent of the funding for the NPGS, with the states, through land-grant universities and state agriculture experiment stations, supplying the rest. “Without that recurrent federal and state support, the NPGS would not exist,” says Peter Bretting, a senior national program leader for the USDA/ARS. “The most daunting challenge currently facing the NPGS is to meet the strongly increasing demands for its germplasm and information while faced with a shrinking capacity to meet those demands.”

Funding cutbacks to many federal and state research facilities, universities and other public organizations are causing growing concern about the future viability of this essential system.

“What we see as a concern is ensuring that the NPGS has adequate funding and has the resources necessary to make sure that we are addressing the evolution of the process as we go along,” says LaVigne. “We are seeing various collections being somewhat endangered; for example, when a professor retires at a university, who is going to pick it up, and does the NPGS have the resources to be able to take on that responsibility? One of the things we have to make sure of first and foremost is that the resources are available to enable the NPGS to continue to be a strong system.”

The seed industry plays a critical and supportive role in the system by multiplying and characterizing seed stocks, collaborating with NPGS staff to conduct joint research projects, donating germplasm to genebanks, and educating the public about the NPGS and plant germplasm’s importance to U.S. agriculture and global food security. “Seed industry personnel also donate much time and in-kind support to serve on the NPGS’s crop germplasm committees, technical review teams, and other groups, which furnish invaluable information and technical input for the NPGS’s operations,” says Bretting.

As leading-edge genomic research advances plant breeding at an ever-increasing pace, the NPGS is faced with additional challenges of managing the increasing number of genetic/genome seed stocks generated, as well as conserving the germplasm of crop-associated microbes, which are important for crop breeding and enhancing crop yields. Genetic stocks include induced and natural mutations, and stocks of genetic oddities and variations on normal chromosomes and genes.

“I suspect that almost every important genetically modified trait has already occurred in nature through spontaneous mutation of one kind or another,” says Cupka. “However, no one was there to identify it and select it, so it grew and then it died. If we continue to collect germplasm and maintain germplasm from all around the world from all the different species, we will maintain genetic diversity and natural mutations that occur—and we will find that, yes, it already happened, yes, we were able to screen for it effectively and, yes, we were able to move it into the commodity markets much more quickly than if we had to create it synthetically later.”

Staff members at the National Seed Storage Laboratory in Fort Collins, Colo., preserve more than one million samples of plant germplasm. Here, technician Jim Bruce retrieves a seed sample from the 0 degrees Fahrenheit storage vault for testing. |

Maintaining Biodiversity

One of the NPGS’s major responsibilities is acquiring and conserving the germplasm of the wild relatives of crops, which include genes that could be invaluable in ensuring the future of agricultural production.

“As we continue to improve and modify our breeding techniques, the NPGS becomes even more important,” says LaVigne. “We are able to look at and mine the various tra

its that may be in varieties that we didn’t necessarily need out of that variety before, but now it’s got that trait we need for either oil quality or nutrition or other factors that you can target and breed with more quickly. With a strong NPGS, we have good information and data-mining capability, and will help breeders address issues as we go forward.”

The NPGS’s role as the foundation of plant breeding in the United States is well recognized by the seed industry and is something it is working hard to promote to the agricultural industry as a whole. “The NPGS is the repository of germplasm that breeders can access to find the traits that are important in dealing with the issues that are facing growers,” says LaVigne. “That’s where, I think, we have to step up our activities to communicate with our colleagues in other parts of the agriculture community about how important it is to have a strong NPGS system.”

Angela Lovell