1915

Fire Destroys Louisville Seed House

The wholesale seed house of Hardin, Hamilton & Lewman, 217 West Main Street, Louisville, was completely gutted by fire, which originated in the wholesale whiskey house of N.M. Uri & Co. at 215 West Main Street, on the night of April 1. The fire had gained great headway before it was discovered, having broken out on the third floor, and the highly inflammable contents of the whisky establishment made the place a roaring furnace. The flames had already been communicated to the seed house when the firemen got to work and they were able only to confine them to the two buildings.

There was no interruption to the business of the seed house, temporary headquarters having been opened up in the building at 128 West Main Street, while the members of the company made arrangements for other quarters. When this was written a definite choice had not been made, though it was probable that the company would occupy the building formerly used by Lewis & Chambers, at 228 West Main Street, vacant since the other company moved into the square next to the west.

The loss to the seed company was total, the building being gutted and practically the whole of the large stock of seeds on hand having been ruined. J. H. Hardin, president of the company, estimated the loss to the company at $40,000, while the loss on the building, on which the company had a lease, was estimated at $20,000. The insurance held by the company covered the stock, although it will not provide for the loss of profits that would have resulted from the April business, and it is estimated that much of the month will be gone before operations can be restored to a normal basis. The fire came at a very inopportune time, Mr. Hardin said.

The interior of the seed store was hot as a furnace when the firemen broke in on their arrival and burst into flame immediately. Most of the available fire fighting apparatus of the city was called out and in about two hours more than a million gallons of water were poured into the two buildings, the Louisville Water Company starting supplementary pumps to keep the supply up as soon as the nature of the fire was determined. Such seed as was not roasted was thoroughly soaked, and, though work of salvage was left for Monday, April 5, it was not expected that there would be much of this. When the fire was at its height fuel was added by the barrels of whisky which burst an uncounted number of times and the gutters were running for a long period with flame flavored toddy.

1940

Why No Profit In Seed Retailing?

The question of profit in seed retailing is one that has been bedeviling the retail seed trade for the last eight or ten years, not only what might be termed the regular seed houses of larger size, but the smaller seed stores and firms handling seeds as a side line on a legitimate basis as well.

During this depression period literally thousands of dealers of all kinds were induced to stock seeds as a side line; grocery and general merchants, feed dealers, hardware dealers, etc., all of whom had been used to the usual markup of their particular kind of merchandise, the percentage of markup consistent with anywhere from four to twelve turnovers per year.

These essentially newcomers in retail seed distribution, following their usual markup habit or practice, applied the same percent to their stock of seeds, forgetting that in garden seed they had only one turnover per year, as against four to twelve turnovers annually of their regular lines. Or they may have thought they could sell their seeds on a “loss leader” basis, plainly suicidal.

We do not believe it to be any exaggerated statement to say that in the smaller retail transactions in seeds a markup of 50 percent or more on peas, beans and corn and 100 percent or more on small seeds is necessary for an even break or at best a little better than even break. This is essential when one considers all the hundred and one things that enter into the cost of doing business other than the invoice cost of seeds or other merchandise.

—H.G. Hastings, H.G. Hastings Company, Atlanta, Ga.

Insecticides—A Profitable Line at Indiana Seed Store

Both profitable and interesting, at the same time, is the insecticide trade developed by M. Mack and his unusually attractive Gary Seed Store, at Gary, Indiana. Located in a strong metropolitan area largely inhabited by steel workers with their small gardens and yards, the Gary Seed Store has found it profitable to bolster business with more than a dozen of what would ordinarily be called “sidelines” in a seed store. So strong have the sales in these lines become that they have practically assumed a position of main lines.

Having to do with the protection of growing plants, the insecticide rush comes on mainly after the major seed business is over.

In the insecticide line it is fundamental to understand that most injurious insects which can be treated by insecticides either suck the sap from plants or chew on the plants, and that they cannot do both. Which they do depends on the type of mouthparts they have. The chewing insects can be killed with a stomach poison sprayed on the foliage where it will be eaten. But, since the sap cannot possibly be poisoned, the sucking insects must be killed by a contact poison. If this contact poison is powerful enough to kill the insect it is very likely to also be strong enough to injure the foliage of the plant.

The insecticides are moved to the front of the Gary Seed Store and into the windows as soon as the seed rush lets up. Some newspaper advertising is done, but it is found that if a customer buys seed at the store he is also likely to come back for his insecticides without further prompting.

1965

Seedsmen Always Have Problems

A new calendar year has started; but for members of the seed industry it is only the halfway mark in their crop year … the end of the period of growing and acquiring seeds and the beginning of the period of intensive distribution of them.

Reports we have received indicate that seed supplies are fairly normal. There are some seeds in short supply, a few seeds in over-supply and the majority about in line with demand with a usual small surplus. Seed prices are mostly firm; and the indications are that members of the seed industry should have a fairly good year.

This does not mean that everything will be rosy. Seedsmen have had problems since the early days of the seed industry; and they probably always will have them, because as soon as one problem is solved others take their place. However, this seems to be true in most businesses today. Change has become the order of the day, and we must make changes or pass out of the picture. Yet every time we make changes we run into new problems. It’s a never-ending circle.

Seed Certification—Future Trends As Viewed by a Private Seed Breeder

The subtitle “Future Trends” very definitely suggests that seed certification does have a future. And if it has a future, it surely has had a past. This speaker firmly believes that patterns of future actions are linked with earlier experiences. Perhaps a very brief review of the early concepts of seed certification may serve to bridge the gap between what has gone before, what is reality today, and what the seed industry trends face in the future. Many of you may have had a part in creating the past, in fostering the changes that have been made, and have a clear vision of what is needed in the years ahead.

1. It provided a method by which a recognized organization could place a stamp of approval or guarantee on trueness of variety identity.

2. It provided to the grower of seed a tag or label on which the name of the variety was shown and on which the mechanical purity of the seed was recorded. The quality of seed (germination, weed seed content, etc.) was deemed to be important on this tag because in the begi

nning most individual growers were poorly equipped to properly clean the seed they grew on their farms.

3. It provided to the grower a great deal of assistance in marketing the seed he produced by (a) publishing names of growers whose seed had passed certification and (b) cooperating with the extension and experiment station staffs to maintain eligibility for certification only for those varieties that were on a recommended list.

In short, seed certification agencies in the beginning guided the destinies of seed growers on what they could plant, how they produced it to maintain varietal purity, and gave as much assistance as possible in selling the seed produced.

—Dr. Iver J. Johnson, Caladino Farm Seeds Inc.

1990

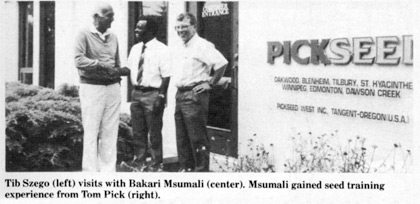

Tanzanian Completes Training at Pickseed

Bakari Msumali, branch manager of the Tanzania Seed Co. Ltd., recently completed a seedsman’s training program at Pickseed, Richmond Hill, Ontario.

This training period is part of a larger program to assist seed personnel in developing countries, and is organized by the International Federation of Seedsmen (FIS), Nyon, Switzerland. Robert Jacobsen of Denmark, who is the chairman of the FIS committee, furnished a list of candidates to Canadian seedsman Tib Szego, who voluntarily organizes training seminars. Szego linked volunteers from the membership of the Canadian Seed Trade Association and the trainee candidates recruited through the offices of FIS. Funding for this project was provided by the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA).

Msumali’s participation in this program is expected to benefit Tanzania’s agriculture. He spent time at Pickseed’s headquarters in Richmond Hill, Ont., at its research center in Blenheim, Ont., and at forage seed conditioning plants in Oakwood, Ont., and Winnipeg, Man. The East African country of 16 million people is considered favored with a good growing climate and productive agriculture. Corn, pulses and vegetables are among its principle crops.

Genetic Testing to Receive Instrumentation Research

Beckman Instruments Inc., Fullerton, Calif., and Native Plants Inc. (NPI), Salt Lake City, Utah, have agreed to jointly develop automated instrumentation for genetic linkage mapping, RFLP analysis and other genetic analyses using labeled DNA probes.

The system is expected to permit genetic studies to be done more quickly and at less cost. Genetic mapping may be used to develop products that help increase crop yield, enhance plant nutrition and lower cost of agricultural production.

Beckman engineers will work with NPI molecular biologists and geneticists on the automated analysis system. Beckman will manufacture and sell the instrumentation and become a distributor of certain NPI probes, genetic information associated with those probes and software that will be marketed with the system.

Wilbur-Ellis Acquires Chipman’s U.S. Seed Treatment Business

Wilbur-Ellis Company, San Francisco, Calif., has acquired the U.S. seed treatment business of Chipman Chemical. As a result, Wilbur-Ellis now owns the registrations, existing inventories, accounts receivable for the business, and the use of the following trademarks: Agrox, Agrosol, Gammasan, Granol and Granox.

The former Chipman seed protectant product line and pending registrations will be formulated and marketed by Wilbur-Ellis nationally through its distribution network, along with the company’s existing product line of seed protectant products and application equipment.