Increasing food production while decreasing agriculture’s foot print, that’s the target today’s seed industry leaders are required to hit.

During the past century, crop yields have increased substantially thanks to the efforts of plant breeders and the seed industry. Corn yields have increased the most, followed by cotton, soybeans and wheat, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service.

Looking at corn, USDA reports that average per-acre yields in the United States rose from 20 bushels in 1930 to about 70 bushels in 1970 and reached 140 bushels in the mid 1990s. Soybeans and wheat follow the same upward trajectory, just not quite to the same degree.

While a number of factors, such as improved pest management, mechanization and fertilizer use contributed to these yield increases, studies conclude that 50 percent or more of the overall yield gain for corn, soybeans and wheat can be attributed to genetic improvements in plant varieties.

It’s known that U.S. agriculture is the gold standard for producing an abundant supply of affordable, safe and nutritious food. This is not changing but the demands are.

“Food is becoming a pressing issue,” says Stephen Baenziger, a University of Nebraska, Lincoln, professor and plant breeder. “Norman Borlaug thought that the Green Revolution would buy us about 30 years, and we’ve lived on it probably 40 to 45 years. It’s coming back and we are going to need that second Green Revolution.”

Robert “Robb” Fraley, executive vice president and chief technology officer for Monsanto, is optimistic about the future of agriculture. “This has got to be the most exciting time to be in agriculture and, I would argue, probably the most important time,” Fraley says. “Today, we are beginning to see brand new platforms with data science and the ability to map fields and subdivide them into small segments to farm meter-by-meter and really start to optimize yields and productivity. I believe that with the advances in biology and the advances in data science, we will see another Green Revolution.”

This should be comforting given the task facing those in agriculture: to increase food production by 70 percent by 2050 to meet the needs of the expected 9.1 billion people inhabiting the earth, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

But while food production must increase, agriculture’s environmental footprint must decrease, and the seed industry and scientists around the world are shifting their attention to soil quality, old-world crops and biologicals to hit the bulls eye set for 2050.

To help increase the awareness of soil’s role in sustainably advancing yields, the FAO named 2015 as the International Year of Soils.

“The amount of arable soil on the planet to increase agricultural production will not expand,” says Wilson Hugo, an FAO agriculture officer in the Plant Production and Protection Division with a focus on genetic resources, seed policy and seed industry development. “It will probably contract if we keep having issues of erosion.

FAO reports that soils host one-fourth of the planet’s biodiversity but are in danger due to erosion, degradation and expanding cities. Experts estimate that there’s only 60 years of topsoil left if current trends continue.

Armed with this information, a number of farmer-led organizations and companies, including Monsanto, have invested into the Soil Health Partnership. The partnership focuses on innovative soil management practices that reduce tillage, use cover crops and apply plant nutrients differently — all with the goal of growing more food while protecting the environment. As such, Monsanto has made a five-year funding and in-kind technical support commitment to the Soil Health Partnership.

“Emerging agricultural biological technologies can supplement every farmer’s toolbox.”

— Robb Fraley

Sighting In

One company that’s focused on using what’s already in the soil is BioConsortia.

“It’s an area that is garnering a lot of interest right now, not just from the big companies but by mid- and small-size companies, too,” says Marcus Meadows-Smith, BioConsortia CEO. “We are using multiple tools to identify the best microbial teams.”

He explains that these tools include a microbiome analysis, which looks at what microbes increase in response to another input, and DNA sequencing. “We look for high-performing plants under selective pressure, so we have a very efficient model for screening,” Meadows-Smith says.

The team at BioConsortia recently marked a milestone when the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office granted the company a patent for its Advanced Microbial System late this year.

The first wave of products Meadows-Smith looks to bring forward are generalists that have the specific target of improving yield. His researchers also have some trials out that look at nitrogen use efficiency for corn, soybeans and wheat.

“In the mid- to long-term we are talking to partners about filling a specific need,” Meadows-Smith says. “For example, if a company is working on a drought tolerant hybrid, we would work at developing something specific for them and that geography.

“Others include water use or dealing with a pest. Some resistance is starting to develop to the genetically-modified Bt crops; farmers could look to add another GM or Bt trait, or a microbial insectide seed treatment.”

Meadows-Smith says he’s been surprised by the level of interest from the fertilizer industry and their desire to improve fertilizer use efficiency.

“There’s a growing awareness that a large amount of fertilizer applied has not hit the target and resulted in denitrification and leaching,” he says. “Basically, it’s getting lost in the environment.”

In addition to seed-applied microbials, BioConsortia researchers are investigating in-furrow application, which means the microbes go in the furrow and are applied over the top of the seed at planting along with the fertilizer and other starters. One of the benefits of in-furrow products is that it allows more chemistry to be added than what can be put on the seed, Meadows-Smith says.

The BioAg Alliance, Monsanto’s partnership with Novozymes, just announced a 2025 acreage target that will guide its microbials business for the next decade. The target: its microbial products will be used on 250 million to 500 million acres globally by 2025. This is equivalent to 25 percent to 50 percent of all U.S. farmland.

“Emerging agricultural biological technologies can supplement every farmer’s toolbox,” Fraley says. “These products complement the integrated systems approach that is necessary in modern agriculture, bringing together breeding, biotechnology and agronomic practices to improve and protect crop yields.”

Microbial-based solutions are derived from various microbes such as bacteria and fungi. There are approximately 50 million microbes in 1 tablespoon of soil and making use of, and preserving, this biodiversity is important.

Preserving Biodiversity

It’s not just preserving the biodiversity of the soil that scientists are honed in on, they’ve also got their eyes on crop biodiversity.

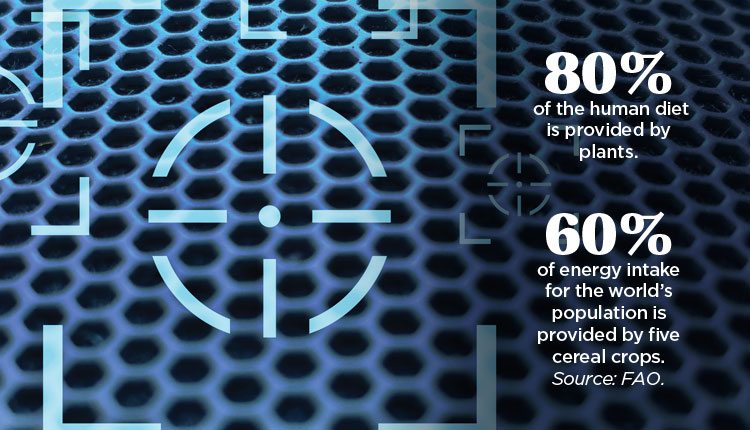

“We are depending more and more on fewer and fewer species,” Hugo says, explaining that there’s a very small group of species that is responsible for providing 80 percent of the energy that keeps the 7.1 billion people on the planet alive. “That is scary.”

Hugo says there are many underutilized species that could be used, and quinoa is one of them. “It’s beginning to get some awareness but those crops, for whatever reason, have failed to become a worldwide recognized crop,” he says. “Perhaps, the highest impact thing we can do from a seed sector standpoint is to get the necessary increase in agriculture’s biodiversity.”

Baenziger agrees with Hugo. “We need diversity, and we need our staple crops — the ones that feed us,” he says. “That’s wheat, and one does not live by bread alone. You need things like beer and barley, and for agriculture, we need things like triticale.”

He says barley is being pushed out of its traditional areas due to an influx of diseases, and as a result there’s a resurrection of winter barley. Triticale, too, is being used in new ways — as a cover crop, as a biomass and as a feed grain. “It’s developing into a really interesting utility crop,” Baenziger says.

Returning to wheat: Wheat provides 20 percent of the world’s protein, and it provides 20 percent of the world’s calories, Baenziger adds.

And advancing wheat yields is another target the seed industry and plant breeders have zeroed-in on.

“Wheat is the most exciting story ahead of us as an industry,” says Kamel Beliazi, regional head of Bayer EMEA (Europe, Middle East and Africa) for Seeds.

In recent decades, wheat has really been an orphan crop compared to corn and soybeans in terms of companies making investments in yield gains, Beliazi explains.

“If you look ahead with the growth of the population and change in dietary needs, things will have to happen in wheat in a similar way as if you look at corn and other crops,” he says. “That’s No. 1. There’s significant excitement from the industry to bring innovation to wheat.”

To facilitate this, Bayer has significantly invested in EMEA for breeding wheat with a wheat breeding hub in Germany and haploid labs in France. In 2015, Bayer completed the expansion of its European Wheat Breeding Center in Saxony-Anhalt in Germany, tripling the capacity of its complex. Investments in the complex surmount to about 15 million euros.

One way of driving yields and bringing innovation to wheat is through the development of hybrid wheat, which is a long-term investment.

“Hybrid wheat is big,” Beliazi says, noting that is promises markedly enhanced yield stability. The company anticipates it won’t be available until after 2020.

Baenziger, who has been working with wheat since 1976, compares the efforts to develop hybrid wheat to that of rice.

“For 30 years people worked in the wilderness on hybrid rice, and now it’s on about 17 million hectares,” he says. “There never was a public sector investment in hybrid wheat the way there was in hybrid rice. These long-term investments — I can tell you a number of times that programs were told they should close their doors … and give it up and they stayed on.

“What we need in the public sector is a foundational program to build the basis for hybrid wheat. And they’ll have to partner with industry, because they are the only ones who will develop the hybrid wheats and bring it to market.”

Back at home in Nebraska, Baenziger says there are four traits wheat must have. “It must survive our winter, because we are winter wheat,” he says. “It must have stem rust resistance. It’s rare but we want to keep it rare; when it comes, it’s like lighting a match in a fireworks plant.

“It must have good agronomics, yield and standability. And it must make a good loaf of bread or bowl of noodles.”

Baenziger explains that Nebraska’s contribution to the global wheat enterprise is that it has some of the most winter-hardy wheat, which goes right into West Asia, where they need winter hardiness.

“We have very good stem rust resistance,” he says. “Our end-use quality is good and our agronomics — that’s always based on where you are.”

He says that also holds true for barley and triticale. “We are probably among the world’s best for winter hardiness in barley,” Baenziger says. “As barley expands or contracts into new areas, our germplasm becomes very important to other people.”

Serving Others

And serving the needs of others is paramount — be it here in the United States or across the world’s vast oceans.

In serving under-developed nations, the FAO is taking much more of an integrated approach than in the past. For instance, Hugo says, within a country profile, the priority might not be to develop the seed sector but to improve the quality of life, the reduction of poverty and hunger. Then inside those macro projects is the strategy on genetic resources and seed production component.

At the request of governments, the Seed and Plant Genetic Resources team helps develop seed policies on all aspects related to seed industry development.

When we go to countries to provide support, the most common thing we find is that farmers haven’t adopted new varieties or technologies, Hugo says. In most cases, the scenario will be that a list of new varieties has been released. Then we search in rural areas and speak with small farmers in communities, only to learn that farmers have not been using them.

“That bridge is extremely difficult to build,” he says. “You need to work within a sustainable system of seed production and distribution of seed of best-adapted varieties to small seedholder enterprises at the beginning. There’s no way of initiating that with a big company arriving into the country. It would not work for them. That is a major challenge.”

Hugo says the biggest opportunity for change is to show the yield differences because that is directly related to food security.

Like Hugo, Beliazi works across a very wide region with many different languages and cultures. “Each and every country is a formidable challenge that I like to embrace with EMEA Seeds and developing our portfolio,” Beliazi says. “EMEA, by nature, is a different society than North America, Latin America and so on. We need to find the right innovation to bring to the market, along with our channel partner to help growers develop healthier crops and face the challenge of feeding a hungry world.”

On this front, Beliazi says Bayer is making major investments in oilseeds. “We entered into the market in 2012, and we have invested significantly in infrastructure in breeding and seed processing in Germany,” he says. “We have assets in Belgium that are working to deploy innovation resources across EMEA.

“The second one is really working closer with the channel partner to develop integrated solutions with our crop protection colleagues to bring on the farm, as well as agronomic services and tailor made solutions that will really make a difference at the grower level. These are the two angles we are working on.”

In the United States, Terry Schultz, president of Mustang Seeds as well as the Independent Professional Seed Association, says one of the reasons independent seed companies are thriving is because of the relationships developed with farmers.

“It’s a relationship business,” says Schultz, who is based out of Madison, S.D. “Our customers know we have their best interest at heart. We report to our customer, not to Wall Street. They know we have access to the best traits and genetics, and anything they need on their farm as far as seed products, we have it available to them.”

Schultz works through his 200-dealer network to deliver seed products to farmers across five states.

“They know Mustang Seeds is a family business, and they enjoy that aspect as most producers are family farmers,” he says. “And many times, they get a black eye in the community or media because they are corporate farms. But these corporate farms have four families living on them. Yes, they are a lot larger by economy of scale, but at the end of the day, they are still a family business and so is Mustang Seeds.”

Meadows-Smith knows the importance of relationships. As a research and development company, his business model relies heavily on partnerships.

“In the past 18 months, we’ve developed a very strong research and development team with 30 scientists and we are still growing,” Meadows-Smith says. “We look to be a big player in the microbial space but we are in the business of research and development, not sales and marketing.

“That’s why partnerships are pivotal. We want to partner with seed companies, fertilizer companies, retailers and distributors.”

Meadows-Smith notes that smaller companies are more agnostic as to where the product comes from and that’s important to realize.

“Our goal is to help farmers deal with challenges such as overcoming drought, nematodes and other factors,” he says. “We are looking to put multiple solutions into the hands of farmers to help increase yields and profitability.”

The key, he says, is to be focused.

Meeting the Needs

While 2050 might seem far away, industry has their sights set on meeting the needs of that time. Industry’s efforts to improve soil health, preserve biodiversity and build relationships will help to achieve this goal.

Fraley believes that as yields and productivity improve, by the time 2050 hits, agriculture will have the opportunity to convert some of the lands farmed today back into forests and pasture. “I think we can be that efficient,” he says. “I know we have the tools, the challenge is ‘will we be able to use them?’”