Is it time for the seed industry to pay attention?

They have been in existence for some time, and they have been signed and ratified by a growing number of countries around the world. However, the Convention on Biological Diversity’s (CBD) Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit Sharing and the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (the International Treaty) have always seemed to exist in the mysterious realm of international policymakers, far away from the everyday business of the seed industry. Is it time for the seed industry to pay attention?

According to Tom Nickson, international policy lead for Monsanto, it has always been time for industry to pay attention.

“When you look at a technology-based company, it is striking to see how important genetic resources are to virtually every aspect of our business and product development,” he says.

In the early 1950s, plant breeders began to use the term “genetic erosion” to describe the loss of genetic diversity, both of specific traits within varieties and of entire varieties and species.

According to the United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organization, “more than 75 percent of global crop diversity has been lost irrevocably over the 20th century.”

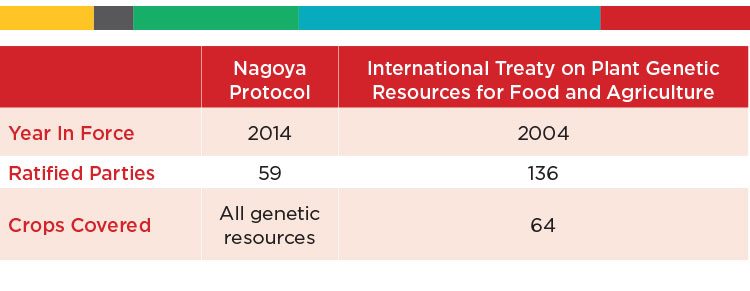

Recognizing the importance of conserving genetic diversity, the international community took action. The Nagoya Protocol and the International Treaty are formal international agreements designed to conserve, sustainably use and equitably share the benefits of genetic resources.

The International Treaty applies specifically to genetic resources used for food and agriculture, while the Nagoya Protocol covers all genetic resources (plant, animal and microbial) and traditional knowledge associated with them.

The Nagoya Protocol recognizes existing treaties on Access and Benefit Sharing (ABS). So, for the most part, plant breeders and researchers who wish to access genetic resources should be able to do so using the provisions of the International Treaty, including the Standard Material Transfer Agreement.

However, according to Nickson, the lines are blurry. Much depends on how countries choose to implement. And he says there are implications for seed businesses.

“Many current national ABS regimes create so much legal uncertainty leading to significant additional costs incurred while sorting out how businesses must operate to comply legally,” he says.

What is the Nagoya Protocol?

The CBD, which came into force in 1993, includes a general requirement that its parties create conditions that will facilitate access to genetic resources by other parties; and implement measures to equitably share the benefits of their use. Its Nagoya Protocal came into force in 2014, designed to set minimum guidelines and rules for fulfilling that CBD’s requirement. At this time 62 countries are parties to the Protocol.

Under the framework of the Protocol, those seeking access to genetic resources must obtain the “Prior Informed Consent” of the party holding the genetic resource and negotiate “Mutually Agreed Terms,” which include the sharing of the benefits derived from the genetic resource.

Benefits can be shared with a financial payment; in a non-monetary form (e.g. sharing research results); or in any way that is chosen by the country or party that holds the genetic resource.

To make the process operable and transparent, member countries are required to designate “National Focal Points” to provide information on how to access genetic resources and negotiate Mutually Agreed Terms. Parties must also identify “Competent National Authorities” which, acting in accordance with national laws, negotiate terms of access; grant access; and document that all of the requirements for access have been met.

National Focal Points and Competent National Authorities are listed in the Protocol’s Access and Benefit Clearing House.

The Protocol also requires that countries put in place monitoring systems and check points to ensure that the users of genetic resources have obtained consent and have negotiated Mutually Agreed Terms. At check points, which can be established anywhere from research to commercialization, plant breeders and others who wish to use genetic resources from a party to the Nagoya Protocol will have to present an internationally recognized certificate (or a recognized equivalent), issued by the Competent National Authority, that identifies the genetic resource; its source and how it will be used; confirms that Prior Informed Consent was obtained and Mutually Agreed Terms were established; and identifies to whom the consent was granted.

Uncertainty in the Unknown

The relationship between the International Treaty and the Nagoya Protocol is not completely clear. The International Treaty defines its scope as applying to plant genetic resources for food and agriculture, held in collections (e.g. gene banks) of its parties. It defines genetic resources as “any genetic material of plant origin of actual or potential value for food and agriculture.”

Some countries, like Canada, maintain that this covers all plant genetic resources for food and agriculture. However only 64 crop kinds are listed in Annex 1 of the Treaty. Some countries maintain that access and benefit sharing of genetic resources of crops not included in Annex 1, and all that are not held in collections (e.g. in the wild) would be purview of the Nagoya Protocol where the process is not as clear. Some important agricultural crops such as soybeans, tomatoes, peppers, sugar cane, ground nuts and some fruits are not included in Annex 1.

Sharing benefits is also a source of concern. Under the International Treaty, those who access genetic resources agree to freely share any new developments from the accessed genetic resources with others for further research and plant breeding. If they want to restrict access with patents or by contract, they are required to pay a percentage of the commercial benefits derived from that development, to the benefit-sharing fund.

The current requirement is 1.1 percent of sales, less 30 percent, of the product or products resulting from the use of the genetic resource. However, the Nagoya Protocol is not that clear, stating only that sharing of benefits is subject to Mutually Agreed Terms.

According to Nickson, there is little recognition of the non-monetary benefits of plant breeding. “Awareness of the benefits provided by public and private breeders to society is alarmingly low,” he says. “Furthermore, within international ABS negotiations, the industrialized breeding sector is viewed by a significant number of negotiators solely as a source of cash and those businesses have a moral obligation to pay for the profits enjoyed. The products seem irrelevant.”

Given the complexity of plant breeding, obtaining Prior Informed Consent from the country of origin is a challenge that brings substantial risk to plant breeders and the seed industry. Under the Protocol, a Party could claim rights over a genetic resource, claiming to be a “country of origin.”

In a presentation prepared by the Dutch Plant Breeders’ Association, Plantum uses apples as an example. Individual villages in Western Europe claim their own apple varieties. Are the individual villages the origin? Is the country? Or is it the near east where all apples are thought to have originated? If so, what country?

Nickson says with uncertainty of origin comes risk. “There are real threats to corporate reputation based in allegations of biopiracy that exist today and require attention.”

Another question is the cost for breeding programs to develop varieties using genetic resources accessed under the Nagoya Protocol. Modern plant varieties are an amalgamation of thousands of “functional units of heredity,” and all can be considered of “actual or potential value” as defined in the CBD. Imagine that in the case of this pedigree, each owner asks 1 percent of the sales of the variety.

According to Nickson, many the current regimes are creating legal uncertainty, and the costs to sort out how to comply are escalating along with the risk of being accused of bio-piracy. He says if the regimes cannot be sorted out, everyone will be impacted.

“It will take longer to develop products,” Nickson says. “Some products will not be developed because costs will be too great or resources will simply not be made available, and some products may be pulled from the market based on legal challenges.

“My biggest concern is that countries may develop crippling policies with devastating effects. In these cases, the poorest and most vulnerable will be unnecessarily disadvantaged. Some seed markets will be unattractive to most needed investment.”

He says plant breeders and seed companies can help. “The effective action to improve the current state of affairs must take place at the national level. Public and private breeders need to engage with national negotiators and become part of the solution within ABS negotiations.”