Companies understand the risks and responsibilities that come with delivering new products to the marketplace.

Megan Townsend

Develop something new — unlike anything farmers use today. Make sure it delivers value and meets the world’s food and agricultural needs. And, remember, it has to comply with domestic and international regulations, while also yielding a substantial return on investment.

That’s the complex challenge seed companies accept when trying to launch a new technology. It’s risky, expensive and takes an entire organization, from scientists to financial advisers, to accomplish, but commercializing new seed traits keeps U.S. agriculture moving forward — increasing crop yields and quality year-after-year.

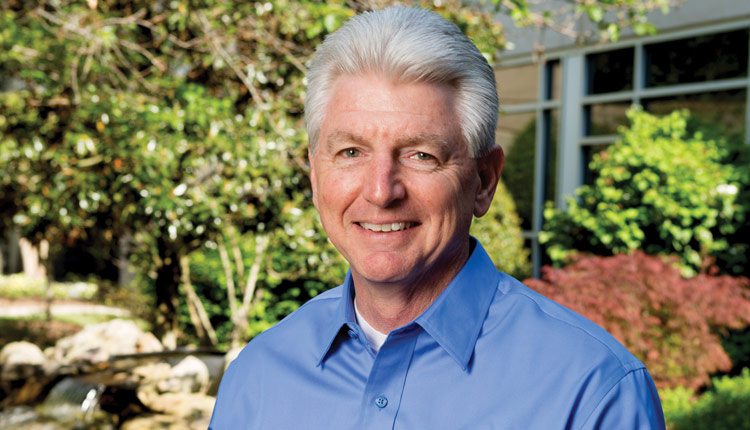

Duane Martin, product lead for commercial traits at Syngenta, estimates that it takes about $150 million and at least 10 years of research, development and regulatory work to launch a new trait.

“It’s a very big decision for companies to make,” Martin says. “There are lots of opportunity costs there if you make the wrong decision. So, it really is all based on what that new trait adds to a grower’s farming enterprise. If it adds something different or better than what is in the market today, then it’s worth the massive amount of resources and considerable amount of time.”

Martin says the driving factor behind launching new technologies for companies shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone — it’s all about adding value for the grower.

“It’s really that simple with a whole lot of other factors rolled into that decision,” he says.

Jeff Veenhuizen, operations lead for Monsanto Technology, describes it as a multipronged approach that starts by determining what the marketplace needs.

“We don’t even start product development until we figure out that it’s going to do something that growers need, so that alleviates a lot of concerns right from the beginning,” Veenhuizen says. “We look at technical success and market success. A product won’t reach the end of the pipeline unless we have the assurance and can make clear claims to the market that the product is reliable, works and is safe.”

Gathering Grower Input

Both Martin and Veenhuizen indicate that obtaining grower insight and feedback is vital to new product development. Companies generate potential product ideas through the discovery phase and then rely heavily on growers to sort the good from the bad. Ultimately, they’re looking for ideas that will result in the highest level of farmer acceptance after commercialization.

There are many information sources companies use to help make strategic decisions regarding what products to develop or what innovation to pursue, according to Veenhuizen. For example, companies conduct focus groups with farmers to determine what drives their efficiency and profitability. They also reach out to academic and industry institutions that work in the areas of insects, weeds, nutrition, animal health, plant diseases and weather. Crop associations also provide valuable insight regarding what is needed in the marketplace.

“We are very active in the Farm Progress Show,” Veenhuizen says. “We try to be transparent by using demonstrations. We want the farmers to come to our booth to discuss these new ideas and give us their feedback. We take that very seriously.”

Mark McCaslin, vice president of research at Forage Genetics International, explains that it’s relatively easy to get a forum of hay producers together by using state and national forage associations.

“We do a lot of homework upfront that helps us establish what the value proposition for growers is,” McCaslin says. “There are a lot of opportunities to interface with growers, and they’re generally not shy in terms of sharing the kind of stuff they’re interested in. If it’s an idea they’re not interested in, they’re not shy about not talking about that either.”

Continually Evaluate Success

With farmer feedback that a new trait will indeed deliver unique value, companies begin technical assessments to determine if the technology will work in real-world settings. They have a system of milestones or checks and balances that allows them to rigorously and objectively evaluate the trait’s success at various points along the pipeline. If it meets the criteria set in place, then it continues through the process to commercialization; however, if it doesn’t meet the criteria, it is eliminated as a viable option.

“We have a lot of requirements that we promised to uphold to the world before releasing this technology, and only after we have met all of these requirements will we launch this product,” Veenhuizen says.

Companies also gauge manufacturing success or how easily a potential trait can move from research and development to production.

And, although they originally determined a need for the trait, they continually assess its potential business success. Since it takes almost a decade for a trait to move through the pipeline, the company wants to ensure there is still a market need, identify where it can be successfully launched, calculate its value and determine its potential return on investment.

The overall goal is to avoid late-stage failures as much as possible because it equates to significant losses for a company in terms of time and money. It can also damage industry and consumer confidence in the pipeline process.

“In the best interest of the entire industry, it is really good for everyone not to have late-stage failures,” Veenhuizen says. “We want to build trust in our process. The pipeline is built to avoid late-stage failures in a really nice way by requiring strict criteria from the very beginning.”

Manage the Decade-long Process

Ten years might seem like a long time to bring a new trait to market, but it’s the timeframe that’s needed to ensure a new trait is safe for farmers, consumers and the environment.

The timeline breaks down into a few years for discovery and invention. Then, companies spend five to six years generating regulatory data that proves the product does what it’s supposed to do and is safe to use. Finally, it takes two to three years to receive regulatory approval after submitting the data package to the government.

“It is an all-inclusive process that involves the research scientists, business analysts, field research organizations and ultimately, the entire commercial organization to bring a trait to the market and actually get it in a farmer’s field,” Martin says.

A company’s size and the development phase determines how many new traits are in the pipeline. For example, at Forage Genetics International, they typically have five or six traits in the discovery phase, two or three in early development and one in commercialization, according to McCaslin. At Monsanto and Syngenta, their product portfolio is much more expansive and results in a pipeline with 50 to 60 traits in it at one time covering many different varieties.

Gaining Regulatory Approval

A company can evaluate whether it’s a good time to launch a trait, but it’s not just up to them. They have to move the trait through the regulatory system, both domestically and internationally, before releasing a new product.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) allows breeders to pursue field testing of new traits. After undergoing years of field tests, extensive review and determination by APHIS that “unconfined release of a genetically modified organism does not pose a significant risk to agriculture or the environment, the organism in question is no longer considered a regulated article and can be moved and planted without APHIS authorization,” according to “The Seed Industry in U.S. Agriculture” published by the USDA.

“The U.S. has a system that is probably the most functional and predictable in the world,” Martin says. “The generally accepted protocol to bring a new trait to the market, even to the export market, has been a very systematic approach that has worked well in the past.”

As long as companies do the right work up-front and collect the appropriate amount of data to submit as a package to APHIS, Martin says the government has been “predictable in returning the regulatory approval to sell a trait in the United States.”

When exporting traits, companies work with industry associations, such as the National Corn Growers Association and American Soybean Association, to determine the best process to follow.

“Those associations work very closely with the industry to advise us on which countries need to approve the trait in order for the grain containing that trait to move freely in the international grain trade,” Martin explains.

A core set of regulations exist that every country has agreed to use when evaluating seed traits, but each country is also allowed to have its own set of specific requirements. There are nuances in the way certain countries want the data presented, but “for the most part, there is a common set of data and requirements used across the world,” according to Veenhuizen.

Rising Uncertainty with China

Obtaining international regulatory approval has worked well in the past; however, it might become much more unpredictable given recent events with China, Martin says.

In late-2013, China began rejecting corn that contained the MIR 162 trait from Syngenta, also known as Agrisure Viptera. Syngenta had received deregulation approval in the United States in 2010 and began selling the trait. The company submitted an approval package to China; however, corn containing the trait made it into the grain system before China granted approval.

“There were several factors there that simply didn’t add up,” Martin says. “First, the import approval in China was delayed long passed when we would have expected it and what history had typically shown us for the Chinese regulatory system. Second, China had been importing corn that may have contained the MIR 162 trait for two years, and then, suddenly, they began rejecting corn saying that it contained an unapproved trait.”

McCaslin describes similar concerns about China’s regulatory process for the hay market. Companies have to obtain approval in the United States before they can submit a data package to China, while other countries allow for concurrent evaluations to accelerate the import process.

“China’s going to be tricky, and all of the biotech companies are trying to anticipate how that process is going to evolve in China in terms of deregulation and how it can be as coordinated as possible with what’s happening in the United States,” he says. “It’s a very significant export market for a lot of U.S. crops, and we’re in a learning phase of what are things that we can do to expedite deregulation in China.”

If the international deregulation process becomes more uncertain, it could potentially stall the launch of new traits, ultimately slowing down overall progress for U.S. agriculture and jeopardizing the country’s competitive advantage in continually improving yield and quality year-over-year.

“It should be concerning to all of U.S. agriculture to see a significant new technology impeded by the actions of a single country,” Martin explains. “Those actions seemed not to be related to the technical or safety aspects of the trait, but really seemed to be much more political in nature. It’s an important issue that the ag industry in general will have to address.”

Rising to the Challenge

Seed companies take on what seems like an insurmountable task when they set out to launch a new technology. It has to be unique, deliver value, comply with strict government regulations and, at the end of the day, generate profit. Yet, each year, they deliver, and each year, U.S. agriculture grows stronger.