Biofortification of crops is often done for people in the developing world, but the concept is now finding its niche in the United States.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 610,000 people die of heart disease in the United States every year; that’s one of every four deaths. It’s America’s biggest killer, and a major impetus for bringing a new broccoli to the marketplace.

In the early 1980s, scientists found a wild broccoli variety that had the unique ability to naturally produce higher levels of a compound known as glucoraphanin. This wild variety was cross-pollinated with commercial broccoli and one of the selections became the parent of Beneforté broccoli, expected to arrive on the U.S. market in 2016.

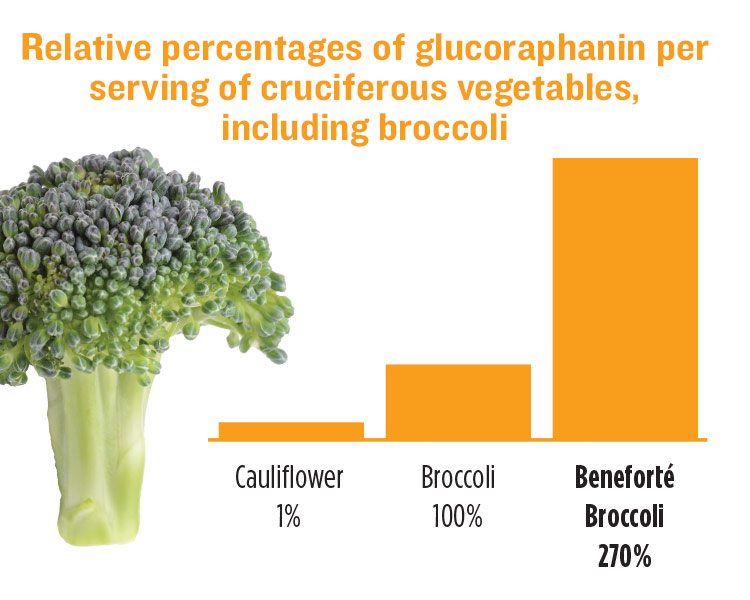

Each one-cup serving of Beneforté broccoli contains two to three times the glucoraphanin compared to a serving of other leading commercial varieties of broccoli. Glucoraphanin is a phytonutrient that may reduce the risk of heart disease.

The development and commercialization of Beneforté broccoli is the result of a collaboration between Plant Bioscience Ltd., Seminis Vegetable Seeds and two of the United Kingdom’s leading research institutes — the Institute of Food Research and the John Innes Centre.

“We hope that by developing products with excellent sensory appeal, people will enjoy eating more vegetables and reap the nutritional benefits that come along with increased consumption,” says Gene Mero, a Monsanto broccoli breeder.

After an initial trial launch in Sam’s Club stores across the U.S., the broccoli was successful enough for a widespread release planned for 2017. It’s expected to be available in limited release for February of next year.

The success of the product is proving how much value biofortification can have in the developed world, and the concept has implications for other crops that Americans consume each day.

Global Idea

Biofortification, the idea of breeding crops to increase their nutritional value, has been researched for several years to help people in the developing world deal with the lack of vitamins and minerals in their diets.

Last year, the first vitamin A cassava shop was officially launched in Ibadan, Nigeria, to increase awareness of this new nutritious cassava variety. Cassava, also known as tapioca, is a major staple food in Nigeria. It’s eaten daily by more than 100 million people, but the commonly available white cassava lacks micronutrients, such as vitamin A, that are essential for a healthy and productive life.

In March, a study published in The Journal of Nutrition showed maize that has been conventionally bred to have higher zinc content can provide enough zinc for a growing child in the formative years. The study showed young Zambian children who ate the biofortified maize flour had higher zinc levels in their bodies. Globally, more than 17 percent of the world’s population is at risk of zinc deficiency.

“The idea is to start addressing some of the vitamin and mineral deficiencies we see in the world by enhancing nutrient levels in those crops,” says Yassir Islam, head of communications for HarvestPlus, which works to end malnutrition in the developing world. “It becomes a food-based approach, where you’re using food coming off the farm to provide people with nutrition as opposed to giving them supplements, which can be expensive to purchase and a challenge to distribute.”

Biofortification is being done with many other crops eaten every day in the developing world, including rice, wheat, beans, millet and sweet potato.

Malnutrition might not be an issue for most people in the developed world, but Islam says poor dietary choices and bad eating habits are something that biofortification can potentially help alleviate.

“It definitely has applications globally, depending on the need you’re trying to address,” Islam says.

Improving Health

Enter Beneforté broccoli. According to broccoli breeder Mero, Monsanto saw a place for the unique product in the U.S. market on both the farmer and consumer level.

“Our R&D teams work to develop seeds that make growing vegetables easier for farmers while also meeting the demands from everyone else in the produce chain — including retailers, food service and consumers,” he says.

The same line of thinking is what inspired Purdue University agronomy professor Torbert Rocheford to bring a new kind of corn to market in the United States. He helped identify a set of genes that can be used to naturally boost the provitamin A content of corn kernels, a finding that could help combat vitamin A deficiency in developing countries.

Researchers found gene variations that can be selected to change nutritionally poor white corn into biofortified orange corn with high levels of provitamin A carotenoids — substances that the human body can convert into vitamin A. Vitamin A plays key roles in eye health and the immune system, as well as in the synthesis of certain hormones.

Vitamin A deficiency causes blindness in 250,000 to 500,000 children every year, half of whom die within a year of losing their eyesight, according to the World Health Organization. The problem most severely affects children in sub-Saharan Africa, an area in which white corn, which has minimal amounts of provitamin A carotenoids, is a dietary mainstay.

Although it has major implications for those in the developing world, Rocheford says the crop is slowly catching on in the United States as well — insufficient carotenoids might also contribute to macular degeneration in the elderly, a leading cause of blindness in older populations.

“Originally, we were breeding it for Africa, but then an organic farmer in Missouri found out about it and was interested” Rocheford says. “So I sent him some corn and he’s growing it.” He believes that if orange corn catches on in America, it might help to speed up its acceptance in Africa.

“It’s better for you than white corn and yellow corn,” he says. “We are just getting started working with a small number of people to bring it to market in the United States. I’m an optimist. Why shouldn’t this be mainstream? They eat orange corn in Thailand and northern Italy. We have documented scientific evidence that it’s actually more flavorful.”

Mero says the same effect has been seen with Beneforté broccoli: “Tests have shown that people either cannot detect a different flavor or taste between Beneforté and standard broccoli, or prefer the flavor of Beneforté. This is likely due to subtle changes in the levels of different sulphur compounds.”

According to Rocheford, popularizing orange corn in America might create a ripple effect that speeds along its acceptance in Africa.

“My view was ‘OK, let’s do Africa with orange corn and later we’ll do America,’” he explains. “Now, we might start growing this in the U.S. so we can help people in Africa, who need it more than we do. It’s a little backwards, but it could lead to big things.”

Good for Growers

As Mero notes, what’s good for consumers can also be good for growers, and Islam agrees. Biofortification was once considered impractical, but that’s turned out not to be the case at all.

“In the past, the conventional wisdom from breeders at international centers was if you try to increase these nutrients, you’ll have a decline in yield,” Mero says. “That was the assumption, but it was soon discovered there wasn’t a tradeoff, that you could have both yield and more nutrition.

“Many of the nutrients we’re trying to increase, like zinc, are things that plants need anyway. When you increase the uptake of zinc from the soil by the plant, it helps the plant to grow better and also benefits the consumer.”

Providing zinc through biofortified wheat and rice could improve nutrition for millions of zinc-deficient people in South Asia, Islam adds.

Rocheford currently has an open pollinated variety of orange corn that yields 85 bushels per acre. Although it yields well, he says the key to its success in America will be marketing it the right way.

“We’re working with organic and local growers who can get a premium at local farmers markets if they have corn meal that’s higher in antioxidants or provitamin A,” he says. “We want to start small and build interest. At Kansas City farmers markets, they’re very excited about it — anything developed through traditional breeding, as opposed to GM, is attractive. There’s a lot of psychology involved. That’s just how it goes.”

Monsanto has a few biofortified products in its pipeline. Examples include a high lycopene tomato and high lycopene cut-and-peel carrot. Lycopene is an antioxidant, which some studies show might help reduce the risk of cancer.

The majority of biofortified crops are created through traditional breeding, but some — like provitamin A-enriched Golden Rice — are created using GM technology. According to Islam, sticking to traditional breeding helps speed acceptance of new crops in places such as Africa, where GMOs have still not gained wide acceptance from a regulatory standpoint.

Still, Islam says genetic engineering will have its place in the future of biofortification.

“You see what you can do with conventional breeding, and after that there are other technologies that can be used to get the kind of crop you want,” he says.