The floriculture market in Asia is thriving, but new markets await as global interest grows.

has been a journalist and editor for 10 years. After serving as a managing editor for Canada’s largest newspaper chain, he transitioned to ag publishing, where he enjoys writing about new technologies and how they impact seed. Follow Marc on Twitter, @mzienkie.

When you think of the floriculture industry, what regions come to mind? Naturally, you might conjure up images of yellow or red tulips in Holland, wildflowers in South Africa or the Tapis de fleurs in Belgium. But experts say you should look to add Asia to the list.

The Asian floriculture industry is worth billions of dollars; the floriculture industry in China alone is valued at more than $11 billion, according to China Horticultural Business Services. Yet, a Google search of the term “Asian flower industry” turns up virtually no industry organizations or groups representing floriculture in Asia

as a whole.

That lack of representation is something Heidi Wernett, owner of China Horticultural Business Services, is out to change. Specializing in strategic agribusiness development, planning and project implementation for companies, organizations and governments, Wernett is considered one of the foremost authorities on Asia’s floriculture industry as

a whole.

Asia holds great potential within the global floriculture industry that’s not yet realized on a global scale.

“It’s taken years for us to coin the phrase ‘Asian flower industry,’ Wernett says. “People often use the terms ‘Japanese flower industry,’ ‘Chinese flower industry,’ ‘Korean flower industry’ and ‘Thai flower industry.’ But putting it all together as the ‘Asian flower industry’ has taken time.”

Wernett, who is from the United States and holds master’s and doctorate degrees in horticulture and plant genetics, was immediately taken with the potential that existed in Asia for making its floriculture industry one of the most lucrative in the world — and has spent the past two decades living and working in China with the goal of helping the Asian floriculture industry develop.

Driven By Domestic Demand

Unlike other regions that focus their efforts on developing flowers primarily for export, Wernett reports that Asia is focused on supplying the local market. She credits this development to the rapid strengthening of economies in the region, high population densities and consumer perception.

The domestic flower market in Asia, which comprises cut flowers, cut foliage and potted plants, was discovered virtually by accident. “Asian growers thought if they grew flowers and exported them, they would make big profits,” she says. “But exports floundered compared to the growth in the domestic industry. Once the flowers were available, domestic consumers began buying them.”

Flowers have been a crucial part of Asian culture for thousands of years and are an integral component of spiritual and cultural practices, often bestowed upon royalty. “They have always had flowers for the emperor or king,” Wernett says. “But in recent years, the general public has come to see flowers as an important part of everyday life, associated with a healthy lifestyle and prosperity. Also, governments are big buyers of flowers, especially for urban development, as in city beautification projects with flower-lined streets.”

This perception has increased domestic demand for flowers in Asian countries such as Japan where the domestic flower industry is massive. As Asian economies have prospered in recent years, that demand has only expanded. No longer is Asia considered part of the developing world, Wernett notes.

“In recent years, the general public has come to see flowers as an important part of everyday life, associated with a healthy lifestyle and prosperity.”

— Heidi Wernett

“When you write a list of all the countries in Asia, how many of those were once considered developing or underdeveloped countries?” she asks. “Today, that mentality doesn’t exist.”

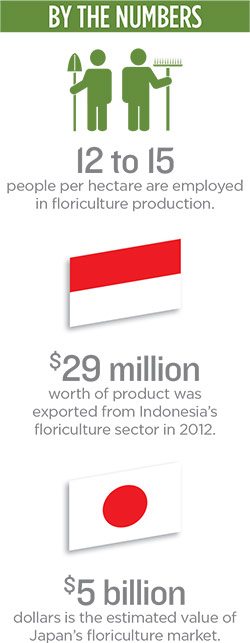

Of the Asian countries, Wernett says Japan is very unique. “Despite a $5 billion flower market, in the past 30 years, Japanese flower imports have never exceeded 10 to 15 percent,” she says. “More than 85 percent of all their flowers are domestically produced and consumed.”

Growing an Industry

Like Japan, Indonesia has seen its industry grow to satisfy a significant domestic demand for cut flowers, foliage and potted plants. With a population of nearly 250 million in an area roughly the size of Alaska, it’s one of the world’s most heavily populated countries. However, its floriculture industry remains relatively small, but it’s gathering steam, explains Benny Tjia, owner of Bogor-based MJ Flora, which is located in the West Java province of Indonesia.

MJ Flora, an ornamental horticultural company, got started in the back of Tjia’s house and grew until it ran out of room. “We keep on growing and expanding, and I expect that will continue,” Tjia says. Today, flower production at MJ Flora spans 13 acres.

Tjia left his homeland for a U.S. education in his early 20s. Having earned a master’s degree and Ph.D in horticulture, Indonesia’s burgeoning opportunities within floriculture brought him back home nearly 25 years ago. Today, he is widely recognized for leading Indonesia’s commercial floriculture industry in new directions.

“Our growers fill domestic demand, where people are eager for cut flowers, but Indonesia has the potential to grow its exports, as well,” Tjia says, noting that while their industry is small on the world scale, there’s a ton of potential. “Indonesia’s biggest growth potential is growing cut foliage because it lasts a lot longer. Singapore is only about an hour and 20 minutes away and Japan is only about eight or nine hours. If we’re serious about it, we have the market.”

While there’s a great deal of potential in cut foliage, Tjia has been focusing his efforts on the bedding plant industry. “We have 365 days of growing here, and there are a lot of wealthy people who don’t mind paying $4,000 in one shot,” he says, noting that the key to improving the industry is education. Tjia has helped send nearly 100 Indonesian horticulture students to participate in an international program at The Ohio State University, where they learn valuable skills.

“We have begonias and that kind of thing, but those are local varieties that have been here for

centuries,” Tjia says. “Many wealthy people travel to America or to the Netherlands and see different varieties. They come back and ask ‘why can’t we do that here?’ I tell them ‘we can, except we don’t have the knowledge.’”

Passionate About New Varieties

This enthusiasm for new varieties didn’t always exist in Asian floriculture. It took people like Tjia and Wernett to introduce new ideas to an industry that was skeptical at first. As a graduate student and prior to moving to China, Wernett evaluated varieties for All-America Selections, a non-profit that exists to promote new garden varieties with superior garden performance judged in impartial trials in North America.

When Wernett moved to China, she helped develop flower trials so growers could better understand the value of varieties. “At the time, many growers thought you just throw out seeds and grow them,” she says. “Now they realize certain varieties grow more flowers and certain ones flower earlier and that kind of thing.”

In the Thai flower market, AFM Flower Seeds has been a leading figure in seed breeding and sales for more than 30 years. Through the years, AFM has focused on breeding marigold cut flower varieties in response to high demand in Southeast Asian countries and India. Unlike most cut flowers for which long stems add value, cut flower marigolds are mainly used for garlands in Southeast Asia.

A notable variety development that AFM is credited with is Curcuma. Although it’s usually grown by commercial growers from corms rather than seed, it can be considered the Asian counterpart to the Dutch tulip. Curcuma has been marketed as the Siam tulip. As a result of extensive breeding work, AFM offers an expanded range of this product in their catalog, something not typically found in seed catalogs anywhere else in the world — even within Asia, Wernett notes.

Export Challenges

Despite a thriving domestic market for flowers, exports remain a challenge for many countries within Asia. Indonesia, for example, has seen its exports fluctuate drastically through the years, due in large part to changing economic policies within the country, Tjia explains. According to government numbers, Indonesia’s floriculture industry exported more than $29 million worth of product in 2012. But in 2013, exports fell to $4 million.

“Indonesia’s biggest growth potential is growing cut foliage because it lasts a lot longer. Singapore is only about an hour and 20 minutes away and Japan is only about eight or nine hours.”

— Benny Tjia

“New rules for imports and exports of horticultural plants and seeds make exporting not very worthwhile, especially if there is still a large domestic market available,” Tjia says.

According to Wernett, new markets for Asian floricultural products have opened in Europe in recent years, but breaking into the North American market remains a challenge. Asia’s ability to expand into markets abroad will determine how lucrative its export floriculture industry will become. A major selling point to investors lies in the fact that floriculture employs a huge segment of the Asian population and could potentially employ many more.

“Floriculture employs the highest number of people per hectare than any other agricultural endeavor,” Wernett says. “It’s very labor intensive. The average is 12 to 15 people per hectare in these developing countries in floriculture. It’s a job creator.”