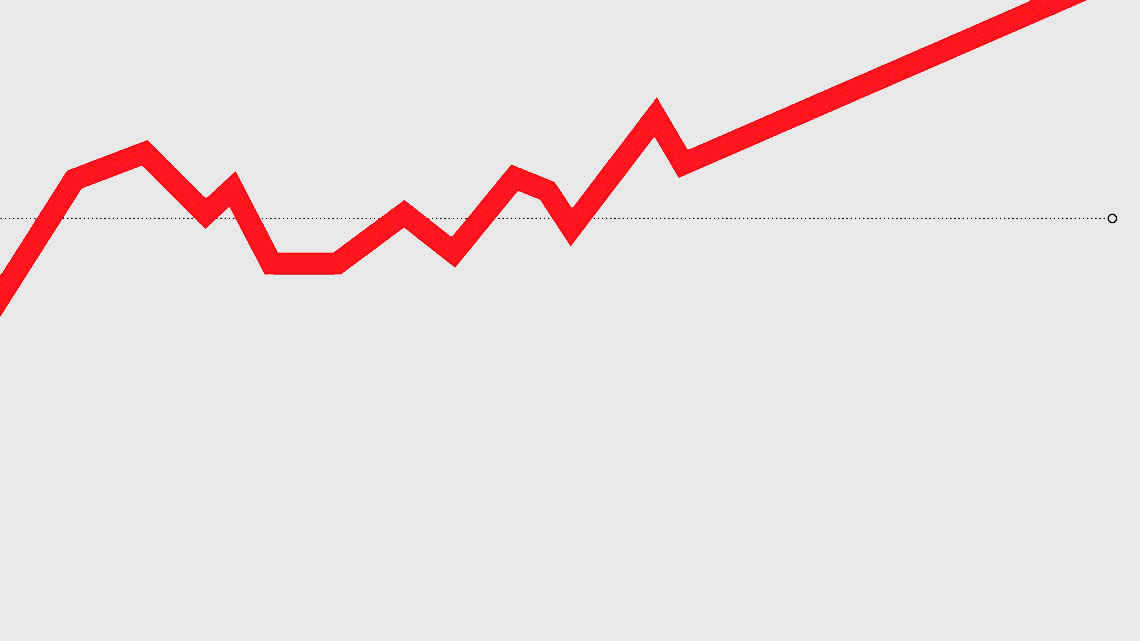

Seed industry analysts say the business climate remains strong and stable.

Despite a few dips, observers say the U.S. and international seed markets remain strong going into 2015 and that the future looks promising.

“The seed industry today is very sound and growing in many ways,” says Thomas “Bud” Hughes, a partner with Verdant Partners, L.L.C. “Improved seed products are being delivered to farmers faster than ever before. The level of investment in research and development, rate of annual yield gains and overall crop and seed values are all at record levels. Adding all this on top of a growing global population and the pressure to maintain that growth while sustaining the environment creates excitement, competition, investment and change in the seed industry.”

Tray Thomas, the founding partner of The Context Network, agrees. “Food supplies are average right now but not exceptionally high, while production is exceptionally good,” Thomas explains. “We are seeing more extreme and irregular weather patterns. That will keep prices and volatility up.”

When going by the numbers, John McDougall, director of crop protection and seeds at Phillips McDougall, says it’s evident expansion has slowed somewhat.

“In 2013 the global seed market grew by 5 percent, aided by growth in the GM trait sector,” McDougall says. “However, the impact of reduced maize areas in the United States and Brazil is likely to have reduced market growth to a rate closer to 1 percent to 3 percent in 2014.”

Thomas says a slight downturn in the industry is inevitable. “We’ve had unprecedented growth and profitability,” he says. “That pace can’t continue forever but, overall, the industry looks good and is one to invest in and find employment in.”

Commodity Prices Hurt Market Values

Analysts say there’s no doubt that lower commodity prices have impacted values within the seed market, particularly when it comes to corn. McDougall says that the U.S. seed corn sector is the largest global market in terms of value. Subsequently, companies noticed when U.S. farmers planted about 4 percent fewer corn acres in 2014, replacing them with soybeans.

“The Latin America 2014/2015 season, which begins with planting in October, has seen a similar trend,” McDougall says, explaining that the Brazilian soybean area was projected up by 3.4 percent while corn is forecast down 2.7 percent.

Hughes says commodity prices always matter, but plenty of other factors influence the bottom line, too. “Seed companies begin to plan their inventories more than a year before they are sold,” he says. “So shifts in planting intentions, whether influenced by commodity prices, trait adoption or just variety or hybrid selection, all play a role in inventory management — a principal driver of profits. These market dynamics vary by crop and country, but these same factors influence everyone.”

Are Changes Eating Away at Grower Choice?

Critics of the current plant breeding system say more needs to be done to support public cultivar development. Findings from the “2014 Summit on Seeds and Breeds for 21st Century Agriculture,” released by the Rural Advancement Foundation International-USA in November, point to a 33 percent decrease in public plant breeding programs across the United States.

Thomas says that might be a fair criticism, but it’s inevitable within a capitalistic society to see the stature of public systems diminish. “It depends what the goal of the public system is,” he says. “If it’s developing new technology and ideas for things not commercially viable yet, then there’s still a good role for the public sector. In an industry that’s commercially viable, the public institution becomes less relevant, especially in areas such as corn breeding and ethanol technology.”

Hughes notes, “Governments around the world have long supported breeding programs for the public domain, but using taxpayer monies to support agricultural research programs that are seen to primarily benefit farmers has, for the most part, resulted in mounting criticism and decreased funding year after year.”

Instead of a public versus private scenario, it makes more business sense to pursue public-private partnerships, Hughes adds.

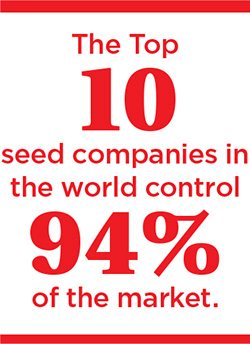

Fewer public breeding programs, coupled with a highly consolidated seed industry, limits grower choice, say the authors of the Seeds and Breeds Summit proceedings. They report that the Top 10 seed companies in the world control 94 percent of the market.

Farmers might have fewer options today, but Thomas believes the quality found within that list is greatly improved.

McDougall says a greater business concentration can be found elsewhere in agribusiness. “Despite the trend in consolidation, the seed industry is not as consolidated as the agrichemical sector,” McDougall says. “Paradoxically, it can be argued that the grower’s choice is growing as the number and complexity of stacked trait varieties of crops is increasing.”

Hughes notes that while the global seed corn industry is heavily consolidated, other segments, due to market size or other influences, remain more fragmented. “Rapidly consolidated segments generally offer more product choices to growers because there are more resources going into research and development, while slower consolidation generally means more seed brands to choose from because they are still heavily influenced by regional companies,” Hughes explains. “Both ways create grower options, but in different ways.”

Where Is the Industry Headed?

Hughes believes that research, targeted at getting the most out of seeds’ genetic potential, will also steer company agendas in the coming years. “Recent improvements in crop genetics have been phenomenal,” he says. “However, we still see that the eventual success of these products lies in selecting the right cultivar for the right field, making the right production management decisions on the farm, and our ‘luck’ in realized weather and other environmental influences. We still see tremendous investments by genetic suppliers, but there is also added emphasis on crop sensors, big data, climate monitoring and modeling, and similar type technologies and information tools.”

Addressing Challenges

All indicators point to the need to continue ramping up food production around the globe. The seed industry has made great strides, but they’ll be challenged to keep with the pace.

“Grain demand is increasing globally, reflecting a growing world population, increased consumption of meat in developing countries, reduced arable area, increased economic wealth in grain importing countries and crop use for biofuels,” McDougall says. “Higher yields will be needed to meet this demand.”

“It is not enough to produce the safest, most abundant and most economical food in the world; consumers must have confidence that they can trust us to do the same, while being good stewards of the land, so that there is no hesitation putting food on the dinner plates of their children, family and friends.”

— Thomas “Bud” Hughes

Thomas believes a particular challenge for farmers in the field, pest resistance, will test the mettle of seed companies, too. To combat these destructive creatures, such as corn rootworm, growers need the right tools.

“We’ve been saying for the past 20 years that the seed and agrichemical industries are intertwined, and now, with resistance issues, that’s even more important,” Thomas says. “Striking the right balance between the industries and how they work together will be important.”

Outside of the field, more work needs to be done connecting the industry with the general public. “The one area that I believe will need the most work is improving the relationship that the seed industry, and agriculture in general, has with the end consumer of our crops,” Hughes says. “It is not enough to produce the safest, most abundant and most economical food in the world; consumers must have confidence that they can trust us to do the same, while being good stewards of the land, so that there is no hesitation putting food on the dinner plates of their children, family and friends.”

Thomas believes that a lack of appropriately skilled human capital will impact the seed industry as well. “It’s difficult to find enough agronomists and IT people, especially at the ground level, who are comfortable working 12 (and more) hours a day for four to five weeks in the spring and fall with less to do during the other months,” he explains. “Agriculture is a complicated business, and ag companies are not considered as sexy as other industries such as Google, Apple or Garmin. When agriculture has to compete with those companies, that’s tough. Progress has been made in this area, but the problem’s not going away.”