A featured segment designed to share business-critical information to seed-selling professionals. Visit SeedWorld.com to download this department and other tools to help you sell seed to farmers.

Farmers might be asking more questions this year about the need for seed treatments. Discover how seed treatments have evolved during the past 20 years and what can be expected in the future.

There was a time that farmers would wait for their fields to really dry out and for soil temperatures to be a bit more hospitable before sowing seeds. A field might be tilled two or three times before a seed ever hit the soil.

Those practices stifled fungi, insects and other disease pressures. There is a reason those were standard practices for so many years.

However, in the past few decades farmers have learned that getting seed into the ground earlier — essentially extending the growing season — will boost yield. In an industry where prices are anything but guaranteed, getting an extra bushel or two from an acre, maybe more, can make a big difference.

According to a 2010 paper from Iowa State University Agronomy Extension, the average beginning corn planting date in Iowa has moved nearly two weeks earlier since the 1970s and early 1980s. Using data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Agricultural Statistics Service, the authors found that back then, the average beginning planting date was late April – April 21 or so in the late 1970s and April 28 in the early 1980s. From 2000 to 2009, the average corn planting date was April 14.

The research showed that growers managing more acreage had to start earlier, and it was common knowledge that “producers face a larger yield reduction by planting too late rather than too early.”

“Now as soon as the field is dry, they want to get it in the ground because they’re worried about the ground getting wet,” says Rod McLeod, regional technical manager for North American seed treatment at FMC Agricultural Solutions. “People are really planting earlier and earlier and exposing the seed to harsher environments.”

And tillage practices have changed considerably in recent years as well, especially as farmers work to slow erosion from both wind and water. More and more fields every year received reduced tillage, or no tillage at all.

A 2010 Economic Information Bulletin from the USDA’s Economic Research service showed that no-till practices were increasing for all major crops in the United States. In 2001, about 16 percent of all corn acreage was no-till. By 2005, it was 23.5 percent and expected to continue rising to close to 30 percent in 2009. From 2003 to 2007, cotton planted in no-till fields rose about 5 percent, to 20.7 percent. No-till practices in soybean fields rose more than 10 percent from 2002 to 2006, to 45.3 percent.

“People are really planting earlier and earlier and exposing the seed to harsher environments.”

— Rod McLeod

However, all these changes meant to help improve yield and environmental stewardship come at a cost. Cooler, wetter soils make fields more hospitable to a slate of soil-borne pathogens, fungi and pests. Reduced tillage keeps the habitats of these pests, fungi and diseases undisturbed.

So as these practices have taken hold, so has the treatment of seeds to combat the adverse conditions. “You don’t know what’s coming at you,” says Dale Ireland, technical product lead for corn and soybean seedcare at Syngenta. “A seed has the most yield potential before you unzip that bag and your seed is in your planter. With seed treatments, you’re trying to protect that yield potential.”

Building Better Seeds

Seed treatments are nothing new but they have come a long way since the 1930s when mercury was used to stave off seed-borne diseases. Mercury treatments stopped in the 1970s when health issues became clear.

Today, it’s common for seeds to be treated with at least a fungicide. In fact, most hybrid corn, which makes up 97 percent of the crop each year, is treated before it gets to a grower’s hands.

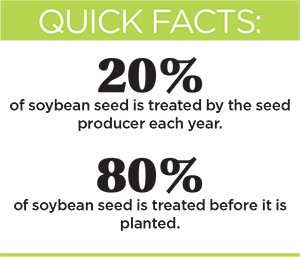

However, other seeds, specifically soybeans, aren’t automatically treated. About 20 percent of the soybean seed each year is treated by the seed producer, but the rest is shipped to distributors untreated. Some will be treated by the distributor, but some will be sold to growers who will have their own treatments added either by the distributor or someone locally.

“Fundamentally, people generally start with a fungicide,” Ireland says. “Most have gone to a fungicide/insecticide now. As farms get larger in size, seed treatments are low-cost and efficient and there will be more focus on them.”

By the time it gets into the ground, about 80 percent of the soybean seed is treated. The rest is left untreated for a number of reasons. Some might be planted later in the season, when disease pressures are lower. Sometimes growers leave a portion of their seed untreated in case they do not plant it. Untreated seed can be marketed as grain at a local elevator, but a grower would need to pay for proper disposal of unused treated seed.

Other than that, seed treatment specialists say there is just no reason not to treat seed these days.

“It smooths out the bumps. It’s like a safety net,” says Kevin Brost, global director of seed treatment at FMC Agricultural Solutions. “You cannot predict conditions. Every year is different. In most fields, there is a wide variability in growing environment. Seed treatment is the best way to ensure stand establishment and maximize that stand.”

Brost says growers are aware that seed treatments are beneficial, but he says there is still a lot of education that could help them make good decisions for their crops. “Sometimes you open the bag and see pink seed and say ‘this must be good,’” Brost says. “But there’s more to it than that.”

Different regions will harbor different pests or pathogens. Even within a few miles, soil types could be different, changing the type of fungicide or pesticide necessary to protect seeds. Growers can take current soil temperatures, moisture levels and other factors into account when deciding what they’d like on their seeds.

“By having a comprehensive seed treatment on those seeds, the greater your chances of a strong stand being established,” Ireland says.

And while holding off disease, fungi and pests is important, there are a host of other treatments that can not only protect plants, but boost their growing potential.

The addition of biological components can increase the length of protection for plants. Some seed treatments add beneficial bacteria that have a symbiotic relationship with plants. Those rhizobia bacteria, which can complement a seed-applied biofungicide, provide nitrogen to the plant in exchange for a place to thrive on or in the plant’s roots.

Many companies are looking for more ways to complement a plant’s genetics so that seed treatments can enhance a plant’s traits that might boost health, resulting in greater yield.

“We’re talking about optimizing treatments that we put on seeds so that we can do more with less,” McFatrich says. “We have a moral obligation to work toward feeding 9 billion people by 2050.”

On top of that obligation, many growers are taking measures to improve the environmental footprint of their land. Tillage practices are a part of that, but so are seed treatments, which require far less of an active ingredient than broadcast sprays would on a field. Those large-dose sprays are often too late, Ireland says, noting that they are applied after a problem has been detected. That means yield has already been hurt.

“By having a comprehensive seed treatment on those seeds, the greater your chances of a strong stand being established.”

— Dale Ireland

“There’s such a small amount of active ingredients with seed treatments and it’s so efficient when compared to broadcast sprays on a field,” Ireland says.

Brost agrees. “As a tool for crop production, seed treatments are fascinating,” he says. “If you were to spread the chemicals we’re using as seed treatments as a foliar application on plants, you’d need multiple times the dose.”

And many diseases that arise in early crop development can’t be controlled by spraying. “You don’t really have any other options to control for those besides seed treatment,” says FMC’s McLeod. “There is no rescue for those. Once they’re there, the plant is dead. With seed treatment, you’re controlling it before you get that damage.”

Cost And Benefits

Even with their efficiencies, there is a cost to having seed treated. The question is whether the return on that investment is worth it.

A University of Wisconsin-Madison paper from early 2014 looked at the risks and profitability of using seed treatments for soybeans based on seeding rates. According to the authors, “a fungicide/insecticide seed treatment reduced economic risk and increased profit across an array of environments, seeding rates and grain sale prices.”

The study also showed that to realize the lowest risk and highest profit boost with the fungicide/pesticide combination, seeding rates should be lowered to the economically optimal seeding rate based on sale price. In other words, it might be better to plant fewer seeds per acre. In the tests, planting 16 percent fewer of the fungicide/insecticide combination seeds did better than the fungicide only or untreated seeds.

Brost says the cost for many seed treatments is less than a bushel per acre. But the return is much greater. With soybeans, he estimates a return of three-plus bushels per acre. With corn, he says it can be as high as 10-plus bushels per acre.

“It should be much more commonplace than it is. It is the least expensive thing you can do to protect your crop and increase your yield,” Brost says. “There should be no reason to not treat. The questions should be what to treat with. A solid understanding of your seed’s genetics, strengths and weaknesses, along with your field situation, is necessary to choose the most suitable seed treatment.”

The Future

Experts see a number of directions for seed treatments in the coming years. More effective fungicide/pesticide combinations are being tested all the time, especially with new biological treatments such as biofungicide or system reach, which some biological seed treatments provide, inducing the plant to trigger and enhance some of its own ability to resist some level of disease infection.

“We are working to be better able to fine-tune and complement the genetic package,” McFatrich says.

That might include helping plants deal with abiotic stresses such as heat, drought or nutrient deficiencies.

Ireland says nematicides are also starting to catch the eyes of some growers, especially those who deal with soybean cyst nematodes, small roundworm parasites that attack the roots of soybeans.

“The nematicides are the biggest growth area we’re seeing with growers who want protection for their crops,” Ireland says.