Corn owes much of its success to plant breeding advances that have increased yields and produced more and better stress-tolerant varieties. But with corn prices lower than they’ve been in years, how have productivity increases played a role in the current supply situation?

Innovations in plant breeding in recent years have enabled corn to better withstand drought and other environmental stress conditions. If not for these advances, the drought of 2012, had it happened 20 years earlier, might have had a much larger impact on the nation’s corn supply than was the case two years ago.

A veteran journalist, Mark has more than two decades of print and broadcast experience. To read more articles written by Mark, visit SeedWorld.com.

The development of more and better stress-tolerant corn varieties is among the factors contributing to increased yield gains and overall corn production in the United States. But in a year such as this, when demand lags supply and a bumper crop drags corn prices to their lowest levels in years, farmers faced with declining profits might be questioning corn’s lofty position among U.S. crops. Has corn become too successful?

Chris Hurt, a Purdue University Extension agricultural economist, acknowledges plant breeding advances have boosted productivity, but cautions against pointing fingers at higher-yielding varieties for sagging prices. Increased productivity, he says, is just one of a number of contributing factors behind the current supply situation, which follows years of rapid demand growth — first spawned by the push for corn-based ethanol in the previous decade.

“If you have much surge in demand, it pushes corn prices very high,” Hurt says. “You shift acreage into corn; you turn the plant breeders loose; and there’s a lot of incentive to find whatever genetics you can to get that little bit more yield. Supply has now caught up with that demand, and seed technology is part of what helped.”

However, Hurt points to numerous other factors that contributed to the surge in corn production. In addition to vast increases in planted corn acreage, input technologies have been more intensively used in an effort in enhance yield and improved management practices, such as irrigation, have greatly enhanced land productivity.

There’s also the weather to consider. Hurt says good growing conditions have also had a hand in productivity increases this year.

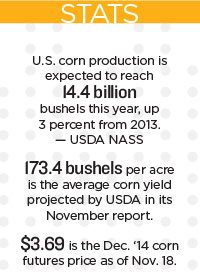

“It wasn’t the genetics that caused us to go from 125 bushel per acre corn in 2012 to 175 bushel per acre corn this year,” he says. “A little bit of that was increased productivity, but most of that was weather. Seed technology was a contributor, but it sure didn’t do it all.”

One way to slow down the supply expansion in the U.S. would be to have farmers plant less corn and switch to other, more profitable crops. It remains to be seen how this plays out next year, but there’s also the question of what kind of impact the current corn supply/price picture might have on future corn breeding endeavors.

The answer, according to Margaret Smith, a Cornell University professor who focuses on corn breeding, is not much — at least long term. She says that’s because private and public sector breeders operate on a much longer cycle than the annual cropping season.

“Investments in research … pay out on a longer time frame,” Smith says. “What you invest in research this year, is not going to be a variety next year. It’s going to be a variety five, six, seven years from now. The short-term ups and downs of the corn market, I’m not sure they have a huge affect on the amount of investment in research and breeding in the private sector.”

Jode Edwards, a research geneticist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service who studies quantitative genetics and maize breeding

believes public research efforts aren’t likely to be affected either due to the length of breeding cycles, which last at least five years.

“In the public sector, I don’t think that any sort of annual fluctuations in the supply and/or demand balance is really going to have much impact,” Edwards says.

“In breeding you have these very long cycle times, and generally breeders are most successful when they can maintain consistent objectives over pretty long time periods,” he adds.

“From the beginning of the breeding cycle until there’s an actual hybrid in the market is still a fairly lengthy period of time, and that’s only one breeding cycle,” he says. “Really successful hybrids are the product of … several breeding cycles. It’s a long-term proposition.”

Edwards acknowledges that seed companies negatively affected by reductions in the profitability of corn farming might be tempted to scale back breeding research efforts in the short term.

“Plant breeding is an expensive enterprise. If profits go down in the seed industry, reducing research is an obvious way to scale back investment,” Edwards says. “It’s fairly simple math that companies have to continue to produce quality seed and have to continue to deliver that. One might view those as more fixed costs, while the research might be viewed as something that could temporarily be scaled back.”

Hurt agrees there might be “less of a dollar incentive for some of the seed genetic companies to make maybe as large an investment in the next few years.”

Another important consideration for seed companies, he says, is that their end-users — corn farmers — are generally experiencing cash pressure because of low corn prices and will be more mindful of their input spending next year.

“When your customer has really strong margins and has a lot of positive cash flow, it’s easier to extract some of that if you’re a supplier of an input like seed,” Hurt says. “It’s harder when the margins … of your customer are very tight.”

The result, he says, is that farmers will be “shoppers for technology.”

“It’s not that they’ll reject technology,” Hurt says. “But what they’ll want is the clear link that if they buy technology, that technology has to be profitable.”

Smith says it remains to be seen whether the level of private sector investment in plant breeding research will continue at the pace of the recent past. “If you look backward at the trajectory of yield gains in corn breeding, it’s been a steady … 1 percent or 1.5 percent a year, but the amount invested to achieve that gain has been going up pretty regularly too,” Smith adds. “Those gains are coming at a higher and higher cost.

Seed companies have had to increase their investment to get that extra yield gain farmers have seen during the past decade. “Whether the industry’s going to keep investing more and more to keep yields going in that same trajectory is a really good question,” Smith says. “But it’s unrelated to the short-term fluctuations in supply and demand and grain prices.”