Seeds of Distrust Spur GMO Labeling Bills

A growing number of U.S. states are considering some form of mandatory labeling for GMO-derived food products. Seed World explores the impact such a system could have on the seed sector and what experts in the agriculture and biotechnology fields have to say about it.

It was 10 years ago this past April that rules for the mandatory labeling of foods containing genetically modified organisms came into effect for all member countries of the European Union.

As a result of GM Food and Feed Regulation No. 1829/2003, everything from maize to flour, oils, tomatoes and even wine that contain GM ingredients must now carry a label indicating this information. However, products such as meat, milk or eggs from animals that consumed GM animal feed do not require labeling.

The question is whether the United States could soon follow suit in labeling foods that contain GM ingredients. Currently, only genetically enhanced food that contains a significantly different nutritional property requires a label.

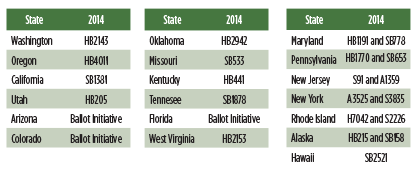

While the federal government has shown little interest in the notion of mandatory labeling for GMOs, several states have proposed their own legislation. Maine and Connecticut passed labeling laws in 2013 and more than two dozen other states are considering proposals, which would require genetically altered food to be labeled.

A recent New York Times poll indicated that 93 percent of Americans feel foods containing GMO ingredients should be identified. The agriculture industry has responded by saying there is no need for a labeling system in the U.S. and such a move will result in higher prices and fewer choices for consumers.

Only 16 states have not introduced some form of legislation requiring the mandatory labeling of GMOs. While 34 states have introduced legislation, only two states — Maine and Connecticut — have passed legislation that requires the labeling of GMOs.

Options Exist

As director of communications for Biotechnology Industry Organization, which is the world’s largest trade association representing biotechnology companies, academic institutions, state biotechnology centers and related organizations across the U.S. and in more than 30 other nations, Karen Batra says a mandatory labeling system in the U.S. could end up being redundant because the National Organic Program already prohibits the use of genetically modified materials in select items, which must be labeled.

“There are already volunteer-based food labeling programs that work perfectly well in this country and provide those kinds of labels for consumers if they want to make that kind of choice,” Batra explains.

On the other side of the Atlantic, Beat Späth is director of Green Biotechnology Europe, a division of EuropaBio — an association that represents more than 2,000 companies active in the biotechnology sector across Europe, including the pharmaceutical, industrial technology, food and agricultural sectors. Späth says he’s not sure there is anything for the U.S. to learn from the European model.

“We don’t have a position or any efforts from outside to change the policy in Europe, but it may not be an ideal system for the U.S.,” Späth says. “If there is a decision to go for some kind of GMO labeling in the U.S., the details will determine the impact.”

But the question of a labeling policy is a very principled one. “Do you want to identify foodstuffs by the quality of the product or the method that they were produced,” asks Garlich von Essen, secretary general for the European Seed Association. “In Europe, we chose the latter; however, we cheated ourselves.”

Because Europe is highly dependent on feed imports, products derived from livestock don’t fall under this labeling requirement. “Consumers live with the false expectation that there are no GMOs in Europe,” von Essen says.

As part of the seed industry, the American Seed Trade Association has taken the position that opposes mandatory labeling of food products that contain ingredients that have been improved using genetic engineering technology. The association believes that “such mandatory labeling requirements are neither necessary nor scientifically defensible, and would run contrary to federal policy established by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.” ASTA also reports that any state law requiring mandatory labeling of foods developed through genetic engineering would create competitive disincentives in the state among different agricultural sectors.

As part of Europe’s food technology sector, Beat Späth (pictured center) questions what the U.S. can learn from Europe when it comes to labeling GMO foods.

Uncertainty Looms

Terry Wanzek and his family operate TMT Farms, an 11,000-acre wheat, corn and soybean farm near Jamestown, North Dakota. Wanzek, who also operates a seed cleaning plant, says it’s too early to say precisely what impact mandatory labeling for GMOs could have on the seed sector, but he has serious reservations.

“As a seed dealer, I think we would have fewer problems providing segregation and isolating and providing the seed for producers who want to grow for whatever market, but there’s a cost to that,” Wanzek says. “I hear a lot of producers say, ‘we’ll give consumers what they want but who’s going to pay for it?’ It’s all connected in my mind.”

BIO’s Batra shares Wanzek’s concerns. She says there is no doubt that mandatory labeling will result in higher prices for consumers. “There’s more to it than just implementing a law or changing product packaging,” she says. “There are all kinds of costs associated with implementing a program like this, and those costs are ultimately going to be passed on to the consumer in the form of higher prices.”

Batra adds that recent studies have shown mandatory GMO labeling could cost the average American household as much as an additional $400 a year.

Claire Parker, a spokesperson for the Coalition For Safe Affordable Food (CFSAF), which comprises a variety of organizations from the American Soybean Association to the National Restaurant Association, is concerned that mandatory labeling could result in fewer food choices for U.S. consumers.

Slapping labels on food items containing GMOs would likely stigmatize those products, she says, prompting retailers to discontinue stocking them on their shelves. Manufacturers will be forced to add warning labels for safe ingredients until they can find more expensive, non-GMO alternatives.

“We want to ensure that consumers have access to safe, affordable food and a full range of options,” Parker says, noting that CFSAF wants any labeling decisions to be based on scientific data, rather than politics.

Farmer, seed dealer and state senator, North Dakota’s Terry Wanzek has reservations about the idea of labeling GMO-derived foods.

Labeling Limits Choice

Späth says the EU’s decision to adopt mandatory GMO labeling has resulted in fewer choices for consumers in member countries. While some labeled items, such as chocolate bars, can still be found, most retailers simply refuse to stock food products above the 0.9 percent threshold that requires the GMO label.

“There’s no real choice for people who would want to buy [GMO products] because there’s almost nothing available,” Späth says. “People who want to buy non-GMO stuff can buy organic and products with GMO-free labels. There is a choice on one end of the spectrum but not on the other.”

However, with the rapid adoption of GMOs and biotechnology, the world is in an entirely different place today than in 2003 when the European Commission adopted the labeling rule. “If the U.S. were to deploy the labeling requirement, you would have to label virtually everything,” von Essen says. “This could be an opportunity to further develop the non-GM market, but that’s a niche market. Europe is the complete opposite.”

BIO’s Batra says it would be a serious mistake if the U.S. were to follow Europe’s lead when it comes to food labeling. “There is hardly any biotechnology in use in Europe and as a result they have a less sustainable ag production system and their consumers pay higher prices,” she says.

Parker says current efforts to adopt state-by-state legislation is “unworkable and will cause confusion among consumers.” And on April 9, 2014, a bipartisan group of lawmakers co-sponsored a bill, known as the Safe Accurate Food Labeling Act, which if passed could undermine state efforts.

Championing the bill is U.S. Rep. Mike Pompeo from Kansas who says “we have got a number of states that are attempting to put together a patchwork quilt of food labeling requirements with respect to genetic modification of foods … that makes it enormously difficult to operate a food system.” Pompeo adds that the campaigns in some of these states aren’t really to inform consumers, but rather aimed at scaring them. “What this bill attempts to do is set a standard,” he explains.

CFSAF believes that, if passed, the proposed bill will remove confusion and uncertainty associated with a 50-state patchwork of GMO safety and labeling laws. The bill reaffirms the U.S. Food and Drug Administration as America’s sole authority on food safety and labeling requirements, and requires the FDA to:

• Conduct a safety review of all new GMO traits before they are introduced into commerce.

• Label foods containing GMOs only if a health issue is found with that trait.

• Establish federal standards for companies that want to voluntarily label their products for the absence or presence of GMO food ingredients.

• Define the term “natural” for its use on food and beverage products so that food and beverage companies and consumers have a consistent legal framework that will guide labels and inform consumers.

While groups such as CFSAF, the American Farm Bureau Federation and the Grocery Manufacturer’s Association applaud the proposed bill, the National Farmers Union opposes it.

“Our member-driven policy supports the authority of lower levels of government and opposes preemption by federal standards,” says Roger Johnson, NFU president. “This legislation would pre-empt state actions to label foods containing GMOs. Surveys have consistently shown that consumers want more information about their food, not less. The prevalence of state-led efforts to label GMOs only corroborates these findings.”

The CFSAF is supportive of legislation that would require the FDA to review all new traits before they are introduced to consumers and establish standards for companies that wish to voluntarily label their products.

Parker says it’s important to note that CFSAF supports mandatory labeling by the FDA if, based on science, there are any health or safety issues with GMOs.

Food Safety Concerns

Food safety was one of the primary reasons why mandatory labeling was introduced in the EU. Späth says many Europeans had lost trust in the food industry following the BSE or mad cow disease crisis in the late 1990s and early 2000s, and felt public institutions hadn’t done enough to protect them.

“In the past few years, there’s been an awful lot of unjustified criticism of the European Food Safety Authority,” Späth says. “It looks like trust has been reduced in the past few years. GMOs are really one of the scapegoats. A lot of people are worried despite the fact our food has never been safer, and that’s been proven over and over — GMOs in particular.”

Despite the adoption of GM Food and Feed Regulation No. 1829/2003 in Europe, research shows most consumers don’t pay attention to food labels. The CONSUMERCHOICE project called “Do European consumers buy GM foods?” conducted a series of studies from May 2006 to October 2008, which included the exploration of purchasing choices in the Czech Republic, Estonia, Germany, Greece, the Netherlands, Poland, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom. It’s important to note that GM-labeled products were not found on the market in four of these countries: Slovenia, Greece, Germany and Sweden.

In examining the purchasing behavior of consumers and comparing it to their perceptions, researchers found that half the respondents (49.8 percent) said they “did not” buy GM-labeled food. But based on bar-code scans, 48 percent of GM buyers thought they had not bought GM-labeled food, while almost 23 percent of non-GM buyers thought they had bought GM-labeled food. Additionally, 30 percent claimed not to know. The study states that “labeling was demanded by participants, yet few of them actually looked at the labels when buying food.”

This research only corroborates what Wanzek, who is also a North Dakota state senator, already knows. Having fought a moratorium on the introduction of biotech wheat more than a decade ago, Wanzek doesn’t believe the general public is clamoring for mandatory GMO labeling. He says a small but vocal group has made it a political issue rather than a safety issue.

Von Essen can relate. “In Europe, GMO labeling is used as a campaign tool,” he says. “If the label is based on science, then it’s just information and we don’t mind it. But does the label read ‘by the way, this product is the most-tested and most-verified’ or ‘we don’t know how this will affect your long-term health?’ Is it a tool for information or a tool for campaigning?”

It remains to be seen if U.S. lawmakers will keep food labeling at the federal level or leave it in the hands of consumers to decide within their own states. Regardless of what happens, it will set an important precedent for science, both in the U.S. and internationally.

Jim Timlick and Julie Deering