Worldwide Seed Royalty Collection Efficiencies

International Seed Federation research is helping to determine the effectiveness of global seed royalty collection processes.

The ISF has released some interesting data on standard seed protection mechanisms used around the globe in its study entitled ISF View on Intellectual Property. The study, released this past June at ISF’s annual meeting held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, provides some new insight and details into global wheat seed royalty systems.

There are several different collection systems used around the globe, which include:

• patents on transgenics;

• plant variety protection to protect the use of the variety in question; this, however, does not protect the genes of the variety;

• contract law is used often in support of other forms of PVP such as contracts enforced by plant breeders’ rights legislation;

• biological properties—for example, in a hybrid—will only provide a collection benefit in the first generation of the hybrid and is therefore well protected from unauthorized exploitation; and,

• trade secrets—in other words, rather than publishing the research, licensing the technology on a case-by-case basis with contracts to use the technology on a confidential basis, and are more suitable for protecting methods or processes of plant breeding.

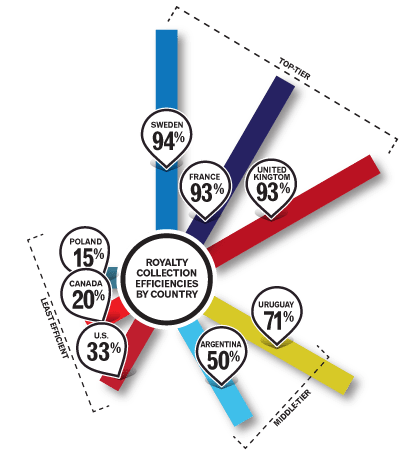

Top-tier countries enforce PVP laws and legislation to support farm-saved seed royalty collection. ·Source: Conclusive Report of the ISF Working Group on Royalty Collection presented at the ISF World Seed Congress held in Rio de Janeiro, June 2012.

Study Findings

According to the study’s summary of findings, many countries differ widely in their efficiencies in collecting potential wheat seed royalties, ranging from 20 percent in Canada to more than 94 percent in Sweden. This wide difference between regions, according to the ISF’s study, is due to the wide variety of systems used, including the following:

• In the most efficient countries, such as Sweden and the United Kingdom, PVP is supported by enforcement tools such as certification, seed laws and strong government support.

• The highest efficiency occurs where farm-saved seed remuneration is collected in addition to certified seed royalties.

• Contractual collection systems for farm-saved seed royalty systems, such as those used in Argentina and Uruguay, can be almost as effective as mandatory reporting systems, as used in the United Kingdom and Sweden.

• Australia is unique in that the breeders’ intellectual property right is extended to the resulting crop, otherwise known as an end-point royalty—instead of operating on the seed portion.

The study points out that in the countries where royalty collection mechanisms are working very well, the most recent act of the International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants, UPOV 1991, and plant breeders’ rights have been adopted. However, countries, such as Canada, which still use UPOV 1978 and have not adopted the revised 1991 act are less effective.

Plant variety protection is currently being used in 70 countries around the world, and the 1991 revision of the act further balances plant breeding rights versus farmers’ rights to retain seed for their own use. UPOV 1991, among both developed and developing countries, is becoming a global standard.

The main difference between the 1978 and 1991 UPOV legislation is the act of 1991 allows breeders to extend their rights to the crop and not just the seed.

In other countries, such as Sweden, which has an extremely high percentage of certified seed purchases at a whopping 94 percent, with only six percent retained by farmers year to year, the majority of the royalty goes to the breeder.

Various Royalty Mechanisms

Australia uses a unique system which collects end-point royalties, which places a levy on the total grain produced from the seed and replaces the seed royalty. According to the study, the system in Australia works for breeders, but does not work very well for the seed trade, as it causes a disconnect between parts of the industry. “Seed sharing now in operation in Australia is a system that works for breeders who then receive market share; however, [it] harms the certified trade system as farm-saved seed is legalized,” says the study.

In other countries, such as Sweden, which has an extremely high percentage of certified seed purchases at a whopping 94 percent, with only six percent retained by farmers year to year, the majority of the royalty goes to the breeder. Meanwhile, in France, only wheat falls under the guideline of its royalty collection system—and this is collected not when the farmer purchases the seed but only when the grain is being sold at the co-op.

Overall, the study would seem to indicate that while a broad range of collection systems exists, it is the prevailing market structure and legislative platform that determines the effectiveness of the royalty collection system applied in any given country.

Shannon Schindle

|

UPOV Background A backbone for the protection of plant varieties is the International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV), hosted by an intergovernmental organization with headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland. UPOV came into being with the adoption of the act of 1961 of the International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants, which was revised in 1972, 1978 and 1991. The objective of the convention is to protect the intellectual property rights of plant breeders to their varieties on an international basis. Membership in UPOV gives plant breeders the ability to protect their varieties in other member countries and gives producers improved access to protected foreign varieties. |