A new technique is changing how researchers visualize plant cells by expanding them.

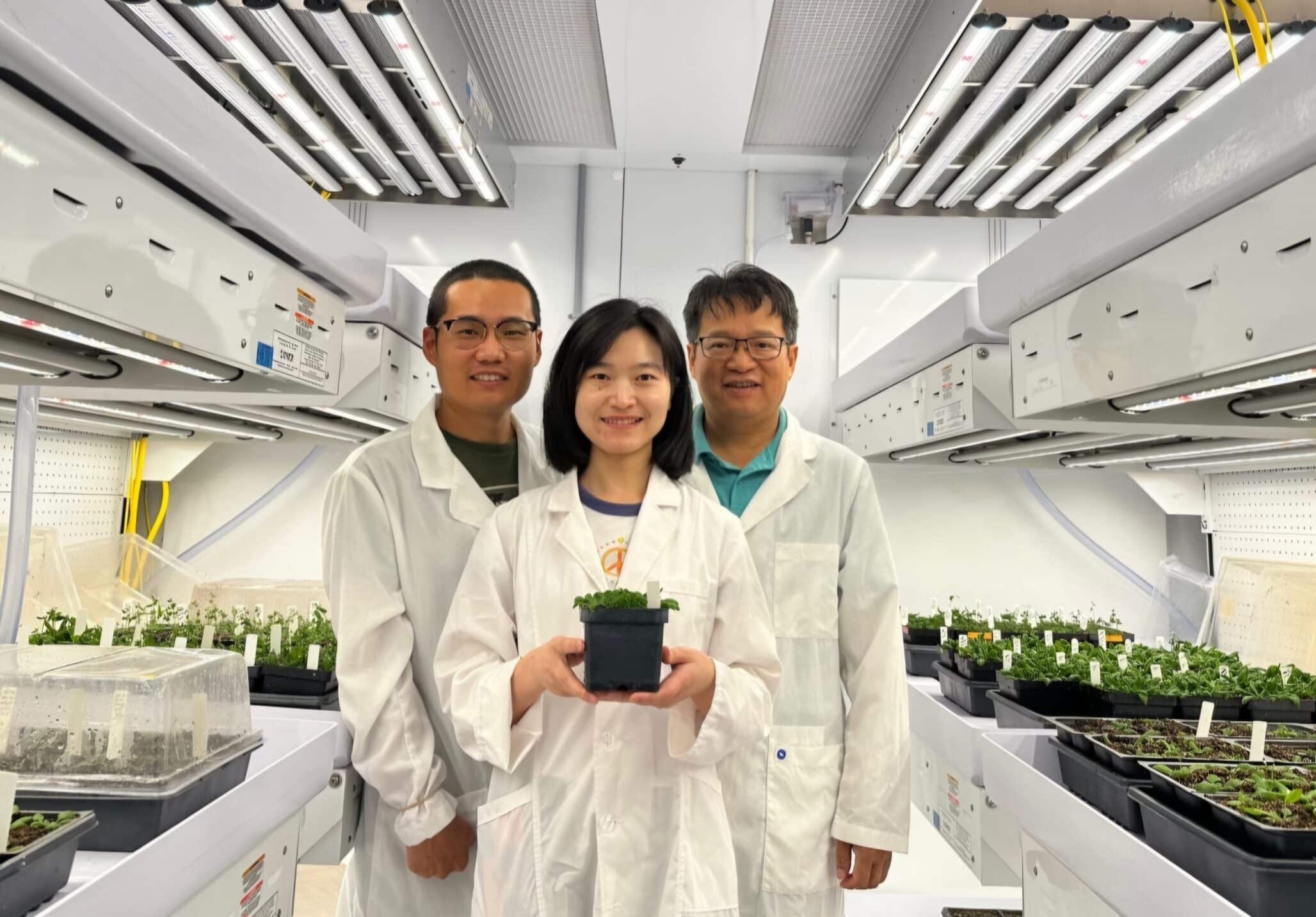

Kevin Cox, an assistant professor of biology in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis and an assistant member of the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center, has developed ExPOSE (Expansion Microscopy in Plant Protoplast Systems), a new approach that brings expansion microscopy to plant research. His findings, recently published in The Plant Journal, highlight how ExPOSE makes plant cells easier to study at high resolution.

Overcoming Imaging Limitations

Traditional microscopy methods have long posed challenges. “We have the low-end microscopes, which are user-friendly but don’t provide much depth and resolution,” Cox explained. “And then the high-end microscopes, where you have really good resolution and data, but it’s a lot to process, and they’re more expensive.”

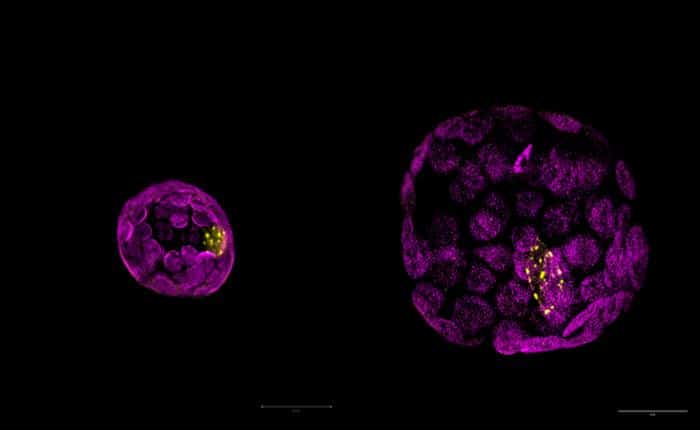

Expansion microscopy offers a new solution. Instead of using high-powered lenses to zoom in, it physically enlarges biological tissues. This is done by embedding the sample in a hydrogel, a water-absorbing polymer that swells without losing its structure—similar to materials used in baby diapers. As the hydrogel expands, so do the cellular structures, making tiny details visible under a standard microscope. Unlike traditional imaging, this method avoids blurring or distortion and is both cost-effective and accessible.

While expansion microscopy has been widely used in animal research, its application to plant cells has been limited due to their rigid cellulose-based walls, which prevent uniform expansion.

Introducing ExPOSE: Expansion Microscopy for Plants

Cox and his team overcame this hurdle by using protoplasts — plant cells with their walls removed — which allowed them to successfully adapt expansion microscopy for plant research. The result is ExPOSE, a method that provides high-resolution imaging of plant cell structures.

By using ExPOSE, scientists can now examine cellular structures in greater detail, pinpointing the exact locations of proteins, RNA, and other biomolecules. This level of visualization is crucial for studying how plant cells communicate and respond to environmental factors. “It gives us a better understanding of where these genes and proteins are, how they’re functioning and how they might play a role in cellular response,” Cox said.

ExPOSE also integrates with other molecular techniques. When paired with hybridization chain reaction and immunofluorescence, Cox’s team achieved even higher-resolution imaging of proteins and RNA. This combined approach creates a powerful toolkit for plant biologists.

A New Era for Plant Research

Although ExPOSE is currently used for studying individual cells, Cox envisions expanding its scope. “We’re trying to understand spatial information at a cellular level and then also, collectively, at a large scale,” he explained. Future research could apply ExPOSE to organs, leaves, roots, and even entire plants, enabling scientists to investigate how cells communicate across different tissues.

At the center of Cox’s research is duckweed, a small, fast-growing aquatic plant ideal for studying cellular communication and gene expression. “Because duckweed is so small, it gives us a model to understand what every cell is doing at a given moment,” Cox said in a news release. This is particularly valuable when analyzing plant responses to stress, disease, and environmental changes.

The ultimate goal? Applying this knowledge to crops. By understanding how plant cells interact and defend against threats, researchers could develop more resilient, higher-yielding, and faster-growing plants—a crucial step toward improving food security and agricultural sustainability.