Reflecting on the ongoing transformations within [the Canadian] system, I find the overhaul known as Seed Regulatory Modernization (SRM) to be a valuable departure from the gradual evolution we’ve observed over the years.

I can’t help but acknowledge the significant role played by W.R. “Wilf” Bradnock, who led the Seed Section of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) throughout the 1960s until the 1980s. His tireless efforts crisscrossing the nation were instrumental in shaping Plant Breeders’ Rights legislation. Together with Ed McLaughlin, the executive director of the Canadian Seed Growers’ Association, they laid the foundation for the establishment of SeCan.

Notably, under Bradnock’s leadership, a crucial shift occurred in 1960 when legislation was introduced stipulating that variety names could only be associated with seed from one of the pedigree classes. This stands in stark contrast to the current patchwork system prevalent in much of the United States, where variety designations are often loosely applied.

Looking forward, it’s apparent that some form of registration and its corresponding regulations must endure. While my perspective has primarily revolved around forage and turfgrass crops, I find it challenging to envision the effective application of variety registration in this domain.

In the realm of turfgrass varieties, initial registration was mandatory. Entrants had to undergo planting in “recognized crop variety trials” overseen by publicly funded crop committees to attain registration. Regrettably, due to budget constraints, local institutions began cutting back on such trials, and turf species were among the first casualties. Simultaneously, the gates of variety registration swung open as simple applications replaced more stringent requirements.

A parallel predicament unfolded for forage species, resulting in the decline of forage testing and subsequently a dearth of performance data.

The cornerstone of the registration policy championed by AAFC officials was the “protection” of consumers, especially our farmer clientele. Despite efforts to show that that farmers were discerning decision-makers, this argument often fell on deaf ears.

The landscape shifts when it comes to cereals and food crops, both for domestic consumption and international trade. In these domains, a case can be made for market forces being left to self-regulate the forage seed sector. However, it remains imperative that effective regulatory oversight continues to govern cereals and food crops.

As I ponder the road ahead, it becomes evident that while some sectors may thrive under the guidance of market dynamics, others, particularly those integral to our sustenance, require a watchful regulatory eye to ensure quality and reliability.

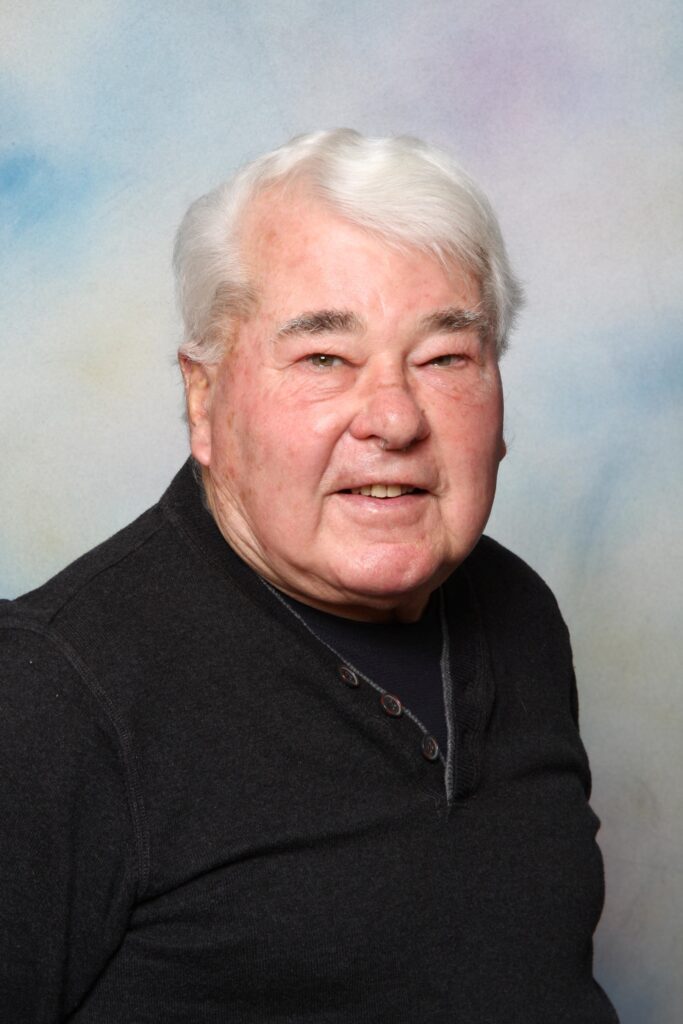

—Martin Pick is a seed industry legend and co-founder of Pickseed Canada