With public plant breeding on the decline in much of North America, our recent webinar uncovered some possible paths forward.

Seed World Group recently took a truly North American view of the public and private plant breeding spheres when we hosted a webinar featuring speakers from Canada, the United States and Mexico to talk about how we can find common ground between public and private breeding programs.

THE PANELISTS

Lauren Comin, Director of Policy, Seeds Canada, Calgary, Alta.

Fernando Gonzalez, Plant Breeding Consultant, Guadalajara, Mexico

Mikey Kantar, Plant Science Professor, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, Hawaii

During this session, we uncovered some key takeaways:

Throughout North America, public plant breeding is under strain.

According to Kantar, the U.S. public sector’s plant breeding programs are facing challenges. These programs are getting older, and they’re not receiving as many resources as they used to, Kantar said.

“The problem is that when people retire from these programs, they often aren’t being replaced. We’re witnessing a shift towards focusing more on crops that have a strong market demand and are considered valuable commodities,” he said.

The breeding programs that continue to thrive are the ones that can bring in significant profits through things like royalties or fees paid by local growers, he said.

“There’s been a shift in priorities due to a decrease in support for these programs that require sustained, long-term efforts. The issue here is that even though we understand the processes involved, breeding new plants takes time. You can’t make a breakthrough and expect to see results in just a month.”

Gonzalez, a retired plant breeder who’s worked with the likes of the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and Corteva Agriscience, said there’s a noticeable uptick in the involvement of the private sector in breeding programs in Mexico.

Most, if not all, of these private companies are competing within the same market segments. Their ultimate goal is to make significant investments in key crops, especially those in lucrative areas, he says.

“We’re witnessing a situation where the private sector’s influence is rapidly growing, while on the other hand, the number of effective breeding programs within the public sector is on the decline,” Gonzalez said.

“Over the years, a few public breeding programs have managed to survive. This is largely thanks to funding coming from farmer organizations and small companies that benefit from the results of public breeding efforts. However, despite these efforts, the overall trend is clear: there’s a significant reduction in the number of active public sector programs and the funding they receive.”

In Canada, both private and public breeding dominate depending on location and crop.

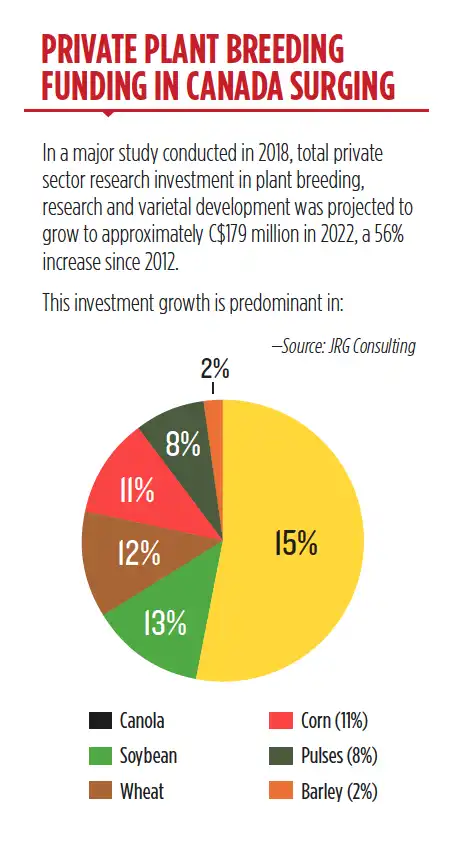

Lauren Comin, policy director for Seeds Canada, said the Canadian landscape of public and private breeding can be somewhat different depending on whether you’re in the West or the East. These differences are also influenced by the specific crop you’re discussing. For instance, when it comes to crops like canola, corn, and soy, where transgenic events and hybrids have gained significant traction, the private sector takes the lead. They dominate the scene, and there’s minimal involvement from the public sector in terms of commercialization.

However, the story shifts when we look at crops like pulses and wheat, particularly in the western provinces.

“In this case, it’s the public sector that holds sway, with institutions like Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada and universities taking the lead. Over time, a strong tradition of producer support, both in terms of funding and advocacy, has emerged in the western part of the country for these pulse and cereal programs,” Comin said.

“This funding from producers is often matched by government contributions, effectively creating a subsidized environment for these programs. This combination of factors, along with the widespread use of farm-saved seed, the absence of a universal seed royalty on saved seed, and a robust registration system for these crops, has effectively kept the private sector from gaining a significant foothold.”

On the eastern side of Canada, there’s a higher prevalence of certified seed usage, which has allowed for more private sector involvement.

The private and public sectors have different goals, which has implications for research.

The primary goals underlying public breeding efforts, which Gonzelez has observed across various regions globally, revolve around enhancing the quality of cultivars for the predominant crops cultivated within a specific country or ecosystem.

“Public breeding programs bear a substantial burden of social responsibility, with an inclination to cater to the needs of the entire farming community, transcending market divisions and similar factors. I’ve also noted that the influence of public breeding is particularly pronounced in countries with lower income levels,” he says.

“The positive impacts span a wide spectrum, from bolstering food availability to curbing the reliance on imports and stabilizing input prices. In essence, these programs seem to have a broader, more inclusive scope.”

Turning to private breeding programs, their core objectives don’t fundamentally differ from their public counterparts: to provide optimal cultivars for farmers. However, there’s a key distinction. Private initiatives are constrained by the necessity for profitability and a return on investment. This aspect is quite clear-cut.

It’s quite interesting to observe how this situation often leads to diverging approaches, and in many aspects, it’s quite a bifurcation, Kantar notes.

It essentially boils down to the availability of funds and the alignment with the demands of farmers. When there’s financial support and a clear demand from growers, a more applied approach becomes feasible, catering directly to those immediate needs.

“Take the example here in Hawaii with papaya seeds. About two decades ago, a widely known variety called Rainbow papaya was released, and it remains highly popular. Interestingly, this variety happens to be a hybrid, and the University of Hawaii Foundation remains a major seed producer, thereby maintaining breeding endeavors through seed sales,” Kantar says.

“One significant advantage we possess in the public sector is the ability to sustain these projects over the long term,” he adds. A prime example of this is a graduate student he’s supervising. They’re currently in their fourth selection cycle for a project that was initiated in 1981.

“Maintaining a project that doesn’t generate direct revenue for over four decades isn’t something you’d typically find in the private sector.”

In Canada, when it comes to public breeding programs, the focus tends to lean towards more upstream research. This often involves what’s known as pre-breeding, essentially research that happens before the final commercialization phase.

In pre-breeding, the aim is to develop traits that will eventually find their way into commercially viable varieties. This type of work is riskier and tends to be more expensive. Plus, a significant part of this effort involves training the next generation of researchers, including students, postdoctoral fellows, and other emerging talents in the field.

On the other hand, private breeding organizations have a different motivation. Their bottom line relies on selling the varieties they develop as soon as possible.

“As a result, they generally focus their efforts on the realm of near-commercialization. They’re geared towards fine-tuning and packaging a product that’s ready for market. This approach ensures that they can generate revenue from their investments,” Comin says.

However, it’s worth noting that upcoming technologies might add some complexity to this relationship in the future.

“For instance, when we consider trait development using techniques like gene editing, access to these technologies might be restricted to those who hold the appropriate licenses or patents. This could potentially alter the landscape of development originating from the private sector. It’s going to be fascinating to observe what kind of developments arise as a result,” Comin adds.

Public-Private Partnerships have a role to play.

A significant portion of public sector breeding does indeed revolve around advancements in technology development, according to Kantar.

“An aspect that I find particularly crucial is the space that exists within the public sector. As Lauren touched on, this space allows us to take on risky endeavors. However, the uncertainty lies in whether these innovative approaches that show promise within our model breeding programs can be scaled up to impact a broader, more extensive audience. This is where the beauty of partnerships truly shines,” Kantar says.

“Looking back, there were instances where the question was, ‘Can we truly put marker-assisted or genomic selection into practical use?’ These scenarios led to remarkable collaborations between diverse entities: companies, universities, and even research centers like the CGIAR centers. These partnerships were instrumental in making these groundbreaking technologies operational. Similar patterns are emerging now with genomic selection. These alliances often involve seed companies, technology firms, universities, and institutions like CIMMYT.”

Gonzalez is an excellent example of how people move fluidly between these different realms, perpetuating this dynamic exchange of expertise, Kantar says.

“What I’ve noticed is that a potential synergy arises when we delve into determining the scalability of novel technologies. We need to discern when a new technology serves as a powerful tool on a smaller scale, perhaps benefiting a specific region, versus when it can be amplified to a national or even international level. This is where those truly fruitful collaborations tend to flourish,” Kantar adds.

However, a key factor determining the success of these collaborations is access to the technology. It’s a facet that’s often overlooked in the broader plant breeding discourse, Kantar adds.

“Our field tends to concentrate heavily on the development of groundbreaking technologies without always considering who has the privilege to access and leverage these advancements. It’s a dimension that warrants much more attention in the plant breeding sector.”

Private industry operates with a distinct urgency because their profitability hinges on making sales. Without a polished, finished product, there’s simply nothing to offer to customers, Comin says.

Consequently, the private sector has honed various strategies and innovations to expedite this process. In contrast, public breeding groups often find themselves contending with governmental bureaucracy, which can inadvertently hinder the pace of scientific progress.

“In recent years, we’ve witnessed a shift in relationships between producer groups and private breeders in Canada. An example would be the recent partnership between Limagrain and the Saskatchewan Pulse Growers. However, this shift hasn’t been as pronounced for cereal crops,” Comin says.

“They continue to be primarily funded by producer checkoffs and rely on government matching funds through these five-year policy programs. Unfortunately, this kind of funding setup doesn’t align well with the long-term nature of plant breeding efforts. With each cycle, the funding gets eroded, budgets become tighter, and government priorities start to shift, presenting challenges for sustaining effective breeding programs.”

Additionally, gaps in research funding can lead to interruptions in breeding pipelines. The shifting priorities of government policies can also result in the abandonment of ongoing work or a redirection of focus. It’s important to recognize that external factors can sometimes work against public breeders’ intentions to introduce new innovations to the market.

“Another aspect in Canada is our registration system, which can create a bottleneck when it comes to the speed of bringing a product to market. If a crop is subject to merit requirements for registration, there are inherent limits to how fast the process can move. So, there are multiple factors that contribute to the pace of progress,” Comin adds.

Public Plant Breeding Capacity in the United States in Crisis

- In 2018, almost 80% of public plant breeding programs reported annual budgets of US$400,000 or less.

- Institutional funds, federal competitive grants, and commodity check-off programs accounted for 67% of program budgets.

- Many programs reported that budget shortfalls or uncertainty “endangered or severely constrained” or seriously constrained their ability to support key personnel, infrastructure and operations, and access to current technology for collecting, analyzing, and applying knowledge from phenotype and genotype data on plant materials in their programs.

—Source: Plant breeding capacity in U.S. public institutions

Watch the entire conversation here: