The U.S. Corn Belt will be unsuitable for cultivation of corn by 2100 due to climate change, according to an Emory University study. By the end of the century, scientists expect climate change to reduce corn yield significantly, with some estimating losses up to 28%.

To prevent this devastating shift, major technological advances in agriculture practices are necessary.

Published by Environmental Research Letters, the study gathers more evidence to prove significant agricultural adaption is required in the Central and Eastern U.S. The adaptation must include crops beyond the major commodities that currently comprise the bulk of U.S. agriculture, shared Emily Burchfield, author of the study and assistant professor in Emory’s Department of Environmental Sciences.

“Climate change is happening, and it will continue to shift U.S. cultivation geographies strongly north,” said Burchfield in a news release. “It’s not enough to simply depend on technological innovations to save the day. Now is the time to envision big shifts in what and how we grow our food to create more sustainable and resilient forms of agriculture.”

The research incorporates spatial-temporal social and environmental information to determine the future of food security in the U.S.

Food, fuel and fiber growth dominates more than two-thirds of land in the U.S., and nearly 80% of the land is cultivated with corn, soy, wheat, hay and alfalfa, said the release. The yields of these crops are in danger due to climate change, resulting in Burchfield’s investigation of the possible impacts of climate change on cultivation geographies.

The Study

Burchfield concentrated on the six before mentioned crops, drawing from historical land-use data and public sources including the USDA, the U.S. Geographical Survey, the WorldClim Project and the Harmonized World Soil Database.

With this data, she constructed models to project where the crops were grown between 2008 and 2019. Her first models utilized climate and soil data, showing 85% to 95% of where the crops are currently cultivated.

Burchfield’s second set of models included indicators of human interventions that effect biophysical conditions that support cultivation. “These models performed even better and highlighted the ways in which agricultural interventions expand and amplify the cultivation geographies supported only by climate and soil,” said the release.

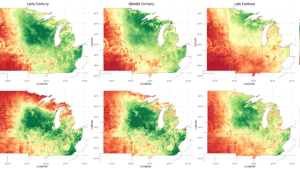

Burchfield then used the models to predict biophysically driven changes in planting to 2100 under low-, moderate- and high-emission scenarios. This test proposed that the cultivation geographies of corn, soy, alfalfa and wheat will shift greatly north, with the Corn Belt in the upper Midwest unable to cultivate crops by 2100.

“These projections may be pessimistic because they don’t account for all of the ways that technology may help farmers adapt and rise to the challenge,” Burchfield shared. “But relying on technology alone is a really risky way to approach the problem. If we continue to push against biophysical realities, we will eventually reach ecological collapse.”

She underlines the necessity for the U.S. to broaden their selection beyond the major commodity crops.

“One of the basic laws of ecology is that more diverse ecosystems are more resilient,” Burchfield added. “A landscape covered with a single plant is a fragile, brittle landscape. And there is also growing evidence that more diverse agricultural landscapes are more productive.”

Monoculture farming takes a great toll on the environment, believes Burchfield. “We need to switch from incentivizing intensive cultivation of five or six crops to supporting farmers’ ability to experiment and adopt the crops that work best in their particular landscape. It’s important to begin thinking about how to transition out of our current damaging monoculture paradigm toward systems that are environmentally sustainable, economically viable for farmers and climate smart.”

Burchfield’s work is far from over. She plans to expand the modeling from her paper by incorporating interviews with agricultural policy experts, farmers and agricultural extension agents.

“I’d especially like to better understand what a diverse range of farmers in different parts of the country envision for their operations over the long term, and any obstacles that they feel are preventing them from getting there,” she said.

Read More About Recent Corn Updates:

Is Increasing Corn Production as Easy as One, Two, Three?

Prospective Plantings Report Shows Soybean, Not Corn, New King Crop

The Future of U.S. Corn, Soybean and Wheat Production Depends on Sustainable Groundwater Use