As tropical pasture seed grows in popularity in Brazil, seed companies look to innovate.

What’s the first seed that comes to mind when you think about seed production? Nine times out of 10, your first thought is probably a row crop, like corn or soybeans.

Brazil has been investing in a whole new side of seed industry production: tropical pasture seed.

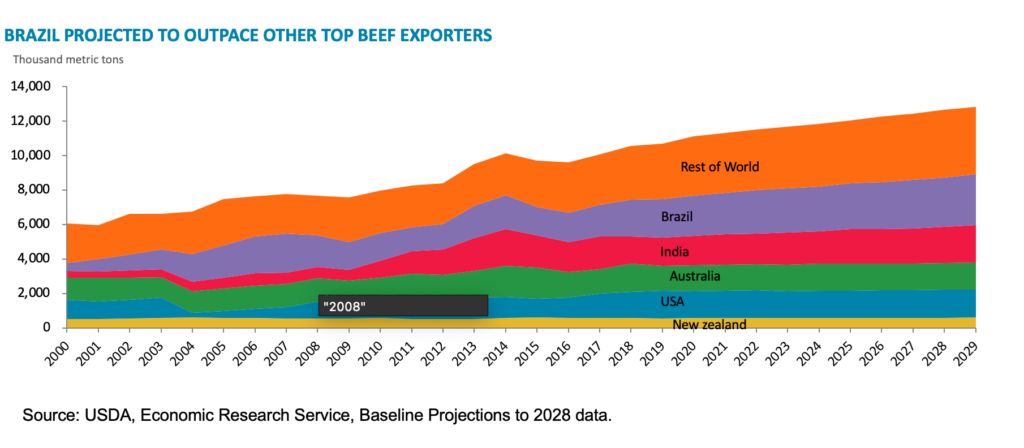

According to a report from Jim Eckles, partner at Strategia Ag, the annual worldwide demand for plant-based and animal proteins has been increasing steadily since 1961 and is projected to be at an all-time high by 2030. By 2050, the global demand for protein is expected to double.

But how does tropical pasture seed factor into the equation? Eckles explains that the efficiency of beef production on tropical pastures has allowed Brazil to become the leading beef exporting country and, according to a USDA report, Brazil will continue to expand its position in the foreseeable future.

Tropical pasture may also improve agricultural sustainability in Brazil and the introduction of improved pasture genetics promises to improve production efficiencies of the producer while creating an attractive seed opportunity.

“We know Brazil as a soybean country,” says Alvaro Peixoto, managing director of Barenbrug Brazil. “But in reality, it’s a pasture country, right? There’s about 70 million hectares of grains consisting of corn, soybean, sorghum and cotton, but there’s 170 million hectares of pastures. Ninety five percent of the herd we have today is in pasture.”

Seed Quality and Purity an Issue

Tropical pasture seed has been actively in Brazil since the 1970s, according to Andrei Nicolayevsky, owner of Semillas Papalotla. The species were first introduced from Australia, but originally came from Africa.

“There’s always been a lot of interest locally — we’re talking about areas which are over 100 million hectares under pasture,” Nicolayevsky says. “However, most of the seed comes from family-based companies that are regional or national in scope. The industry has not drawn for the most part the focus of the big seed companies but that is changing as the market becomes more professional and opportunities arise with the introduction of novel varieties with unique traits.”

The difficulty comes from regulatory issues. To really get larger companies investing in tropical pastures, the industry needs to become more respectable in terms of quality controls, export requirements and intellectual property, Nicolayevsky says.

Quality control, in particular, has been noted as a major issue in tropical pasture seed.

Peixoto says the main breeding programs of tropical pasture seed are focusing on earlier production, foliage production, disease resistance and pest resistance. However, that leaves out seed quality.

“If the seed doesn’t germinate, the product won’t be interesting or beneficial to the farm,” he says.

In addition, impure seed proves as a challenge.

“Regulations in Brazil isn’t that strong for seed quality,” Peixoto says. “In the case of Brachiaria, the law permits the seed to be commercialized with only 60% purity. Then you have another 40% that can be soil, stones or a different material.”

In addition, the question of germination comes into play again.

“When you consider only 60% of the seed, you also have seed that won’t germinate,” he says. “In general, you have a 20-30% germination rate in a bag of 25 kilos of seed, but it’s not really 100% seed inside.”

However, both Nicolayevsky and Peixoto say that times are changing around tropical pasture seed.

Introducing New Technology and New Ideas

One way purity has been increasing, says Nicolayevsky, is through new technology to help harvest tropical pasture seed.

When first introduced, the initial way to harvest tropical grasses harbored from the ground. Meaning, you’d get an adverse reaction in quality and purity due to picking up inner matter dirt.

“Over the last decade, ground harvesting has improved,” Nicolayevsky says. “You’re getting better quality of seed. In addition, there’s changing legislation in Brazil.”

Before the 60% purity requirement, seed quality and purity could be as low as 20-40%. Currently, legislation is being drafted for a minimum of an 80% purity requirement for tropical pasture seed.

In addition, Peixoto says companies are working on introducing new technologies into the market for tropical pasture seed, such as seed coatings and treated seed, to raise the germination and seed quality standard.

“We are looking to bring in seed technologies related to enhancements,” he says. “That means insecticides, fungicides, nematicides, biological seed treatment and more. This will provide more protection during seed sowing in the field.”

Barenbrug is also looking into better tropical seed quality to meet better standards for germination as well.

Hybridization Could Be Key

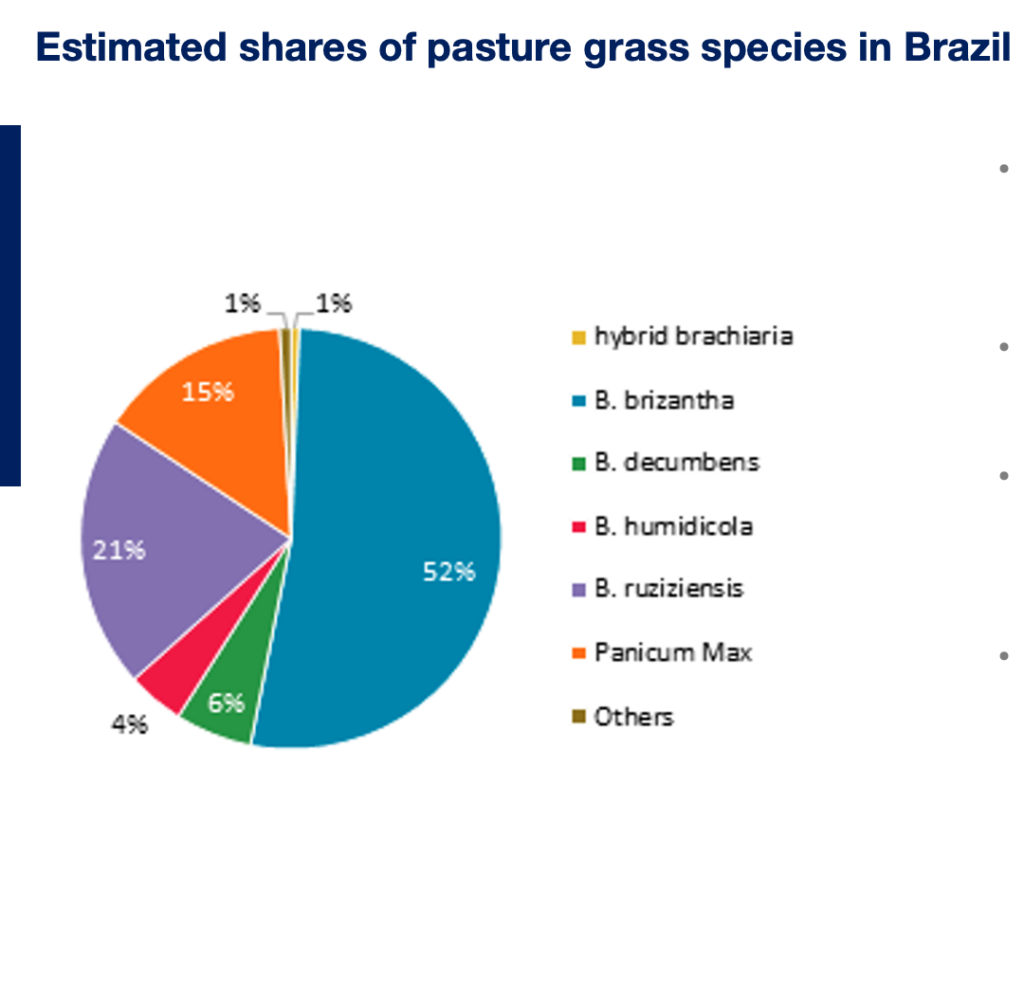

According to Eckles, three Brachiaria varieties introduced 50-plus years ago still represent 75-80% of annual seed sales, but cross-breeding is now possible and “hybrids” that contain combined genetics of the three species will increasingly replace the existing cultivars.

“We’re trying to transform the countryside into something that’s much more productive now, like the flight of a butterfly,” says Nicolayevsky. “There needs to be a metamorphosis in terms of genetics.”

To start this metamorphosis, Nicolayevsky says that Papalotla has partnered with a breeding program at the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) in Columbia. According to Nicolayevsky, this program took an early lead and Papalotla launched the first hybrid from the program in 2001.

“Over the years we’ve seen what we should focus on in terms of drought tolerance, salt tolerance, waterlogging and using them for integrative agriculture,” Nicolayevsky says.

Papalotla will introduce its line of Brachiaria hybrids in Brazil through its own operations beginning this year.

Eckles says that there are three main “interspecific” Brachiaria breeding programs today: EMBRAPA, Barenbrug and CIAT/Papalotla. Barenbrug sells a hybrid licensed from Papalotla, Mulato II, but is now introducing two new hybrids from its own program and Wolf Seeds and EMBRAPA each have a hybrid Brachiaria in the market.

According to Eckles, Brachiaria is a naturally apomictic crop that produces seed without pollination — that seed is genetically identical to the parent, and seed production involves harvesting seed from the cultivar. This means that “hybrids” are genetically stable and seed production does not require the crossing of distinctive lines in production fields.

In addition, Eckles says the use of hybrid Brachiaria in Brazil will grow over time despite a higher seed cost due to the excellent producer ROI from the improved genetics. In Mexico, Papalotla has achieved a market share of 30% with its hybrids and this can be achieved in Brazil as the producers become aware of the benefits.

Growth of the hybrid market will be driven by producer benefits, but the resulting higher seed margins have the potential to convert tropical pasture seed into a highly profitable seed industry comparable to hybrid corn seed.

Pasture Seeds for Climate Change

One of the game-changers about tropical pasture seed in Brazil, however, is the aspects it brings to the table to tackle climate change.

The first? The introduction of a new cover crop to Brazil.

“Due to the intensity of the usage of soil, depending on the region in Brazil, growers can actually have two seasons,” Peixoto says. Meaning, in the summer, growers plant soybeans and immediately after the soybean harvest, growers can plant corn.

Unfortunately, that causes strain on the soil and soil health. But, it opens the door to the possibility of cover crops.

“Now, growers are learning to use cover crops with the corn,” he says.

By using tropical pasture seed as that cover crop and protecting their soil, growers can introduce a third crop to their farm: cattle.

“The tropical pasture seed can give the land a rotational crop and an opportunity to rest,” Nicolayevsky says.

Besides being used as a soil protection, Nicolayevsky says that there’s opportunity in Brazil to renovate current pastures with tropical pasture seed to become more sustainable, instead of working on establishing a completely new pasture elsewhere.

“Brazil can double its meat production by renovating current pasture areas,” he says. “There’s no need to continue going further north into the Amazon to increase pasture areas.”

In addition, tropical pastures help Brazil produce meat and dairy differently due to their genetics.

“These pastures are highly palatable because they have fixed nitrogen due to their deep roots,” Nicolayevsky says.

Those deep roots also help sequester carbon and minimize the carbon footprint produced by cattle.

For the next 10-15 years, Nicolayevsky believes that Brazil can be used as an example to how the beef and dairy markets can become more ecologically responsible.

“We have the ability to show positive effects on climate change, but the question becomes how can we send a message and show how to manage these pastures effectively?” he says. “These new technologies in tropical pasture seed can offer an alternative to what has been stigmatized as a very destructive form of livestock production.

“There needs to be a narrative change of how to intensify pasture management to reap the benefits of the new higher yielding hybrids thus minimizing the need to open new areas for pasture,” Nicolayevsky says. “If we don’t concentrate on the issue of pasture, there’s not going to be the need to sell tropical pasture seed in 10 years.”