Climate change, growing populations and less arable land means advanced farming practices are more important than ever before.

While many in agriculture showed collective outrage over the so-called Impossible Burger, science supporters missed a critical benefit hiding in the controversy. The Impossible Burger is one of the few consumer-facing companies that proudly boasts GMO ingredients, and customers still flock to it.

The team at Impossible Burger showcases the climate-saving benefits biotechnology can provide by showcasing the value of soy leghemoglobin, the key protein element that gives the Impossible Burger its flavor and texture, is a genetically engineer protein. Soy leghemoglobin is made by splicing soybean DNA into yeast, which is then produced in large-scale fermentation.

Seeing this market success, why aren’t GMOs widely accepted?

Frankly, because agriculturalists, from the farm gate, to the lab, to the desks of CEOs, have done a bad job telling the story.

“I think it’s everybody’s responsibility who is involved in agriculture to be involved in communicating,” says Robb Fraley, who commercialized the first genetically modified soybean and now acts as a communicator for the industry. “When I was growing up on a small farm in Illinois, more than half of the people who lived in the state were involved in agriculture. Today it’s less than 1%.

“It’s the responsibility of everyone involved in food and agriculture to reach out to the other 99% regarding the importance of new scientific advances to increase food production and improve the sustainability of farming,” he continues.

The Challenge

Think back to the early 1990s when the FLAVR SAVR tomato was commercialized, albeit short lived. It carried promise to reduce waste and improve flavor, a promise that never came to fruition.

“When the first GMO product, the FLAVR SAVR tomato, came out people had no idea what GMO even meant,” says Kurtis Baute, climate change activist who produces frequent videos promoting science. “It was something that really came out of the dark for them, and it was surprising and scary for many. Because of that, we ended up shelving the idea.”

The long and short of it, if you need a reminder, is public backlash led to pulling FLAVR SAVR tomatoes from the shelf, despite the scientific reality there was no risk in consuming them. People didn’t know what they were, and ignorance bred fear, which manifested itself into nixing the product.

Fear lives on. Activist groups around the world are still fighting against GMOs, despite what has now been more than 20 years of research indicating no adverse human or environmental effects.

And the stakes are high. GMO products could be the key to reducing the impact of climate change and tackling hunger and food insecurity around the world. If science isn’t trusted, GMOs and other modern practices are at risk.

Start the Conversation

For many scientists and experts in their fields, it’s easy to overload people with facts. But the fact is, most people who don’t have scientific backgrounds don’t care about the nitty-gritty details of scientific testing as an expert would. It takes a different approach.

“Anytime you are promoting scientific ideas, you’re going to have people who are not excited about them,” says Kevin Folta, professor at the University of Florida. “It applies to all science, whether you’re talking about genetic engineering or climate change.”

Before starting the conversation, think about how to be a better communicator. It starts by figuring out what neighbors, friends, relatives and, really, anyone cares about. Here are a few tips to get the conversation started the right way:

- Avoid inundating people with facts and figures. Talk about why you care about science. Make it personal and talk broadly about the motivation to promote science. For example, gene editing as a tool to fight hunger and keep farmers in business.

- Cater your conversation to the person you’re talking to. If talking to another scientist, feel free to get into the details and processes. When talking with someone who knows little about science, meet them where they are. They might not want to hear about the statistical approach it took to make research reproducible, they want to know how evidence relates to their values and concerns.

- Ask questions and show empathy. Listen, and show them you are listening. People are passionate about their food, and they should be. Learn more about what motivates them and their fears, acknowledge them and keep this information top of mind when talking about GMOs or other controversial topics.

It’s tough to convert someone to 100% stand behind science, but it’s possible to sway them on several aspects. Understand their backgrounds and why they think the way they do. Employing these three tactics helps get the conversation off on the right foot.

Where to Reach People

The world of communications has changed dramatically since the early 90s when the first GMOs were commercialized. This presents immense opportunity to reach a wide array of people, but that opportunity is not without challenge.

“When I first joined Monsanto, you published papers, did newsprint and that kind of thing,” Fraley says. “Today most of the information people get is on social media, it’s digital. If you’re not on social media, basically, your voice doesn’t count.”

Social media takes the audience from one or two people, to potentially millions. However, it’s not just any post that will capture the attention of the masses, communication looks different online.

“I’ve basically made a career by building over-the-top projects,” explains Baute. “For example, I set up 13,799 dominoes so I could show a timeline of the history of the universe. It was a spectacle that engaged people in personal storytelling so I could talk about real science.

“There are amazing stories to be told, we shouldn’t miss that opportunity,” he continues. “For example, if there’s a new product engage people in personal storytelling about how these products came to be. For some technology, it could be 100 years in the making.”

Not everyone will want to set up nearly 14,000 dominos or live in a bubble like Baute did to talk about climate change, but there’s opportunities to find a fun way to talk about science all the same. Perhaps it makes more sense to tell someone about a personal connection to agriculture and science. Find the story and tell it.

“I once baked a cake in 418 steps to explain genetics,” Baute says. Sometimes it helps to have a little fun when explaining complex topics.

Protect Science for Tomorrow

It’s never been more critical than today to advocate for science literacy. While social media, television and other platforms represent opportunity to talk about science, it also dispels a tremendous amount of misinformation.

“We need to be champions and advocates across the biological, the digital and the agronomic space to amplify the accurate messages,” Fraley says. “Because it’s just 1% of the population in agriculture reaching out to the 99%.”

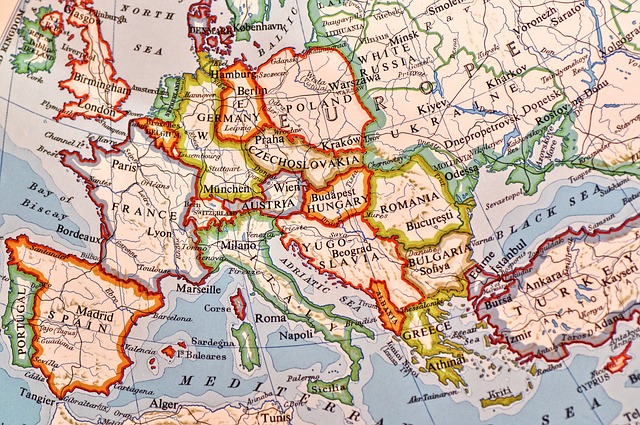

Europe’s Science Desert

Scientists looking for new opportunities to apply the latest and greatest technologies in agriculture: steer clear of the European Union. Policies in the region are virtually devoid of scientific reason and instead are political decisions based on pressure from activist groups, along with misunderstanding and emotions.

For example, the 27-member countries are facing a new proposal called the Farm to Fork Strategy that threatens producer access to technologies and could force them to abandon common farming techniques.

“I’m not sure there was much science involved [in creating the Farm to Fork Strategy],” says David Zaruk, EU risk and science communications specialist. The proposed strategy, in a nutshell, would reduce pesticide use by 50%, fertilizers by 20% and convert 25% of all agricultural land to organic production under the assumption these moves would reduce the impact of climate change.

This isn’t the first-time agricultural practices have come under fire in the EU either. The countries previously passed regulations that require all products made with gene editing technology to be labeled as GMO, regardless of whether or not new genes were introduced in the process.

Researchers in the EU who oppose such rules are between a rock and a hard place, Zaruk explains. Many scientists who support GMOs, gene editing, pesticide use and other common agricultural technologies find themselves without jobs or under attack personally from activist groups.

“Most of the scientist that do speak out are retired,” he continues. Regardless of the risk, Zaruk still speaks out about the benefits of changing policies to enable farmers to use the latest agricultural technologies available and encourages other scientists to do the same.

The EU can, and should, serve as a warning to other countries about what happens when science is ignored in the policy arena, and what happens when agriculturalists aren’t consulted when planning policy.

Canada’s Gene Editing Conundrum

The clock is ticking in Canada. At the end of May, the comment period regarding Canada’s Novel Food Regulations will be over and a decision that could make or break the future of plant breeding will be rendered.

This decision will directly impact how gene editing, through technologies such as CRISPR/Cas9, is used and identified to consumers. The question? Should there be additional regulations for crops created by gene editing like the regulations applied to GMO crops?

“Cas9 [based gene editing] is a great example of something that’s happened naturally for billions of years and now we’re applying a process to our benefit,” says Kurtis Baute, a Canadian native who advocates for science literacy and improving the climate on various channels. “It’s important to communicate the benefit. This technique will be more precise, and we’ll know exactly what we’re breeding for, compared to older breeding techniques.”

CRISPR/Cas9 and other gene editing technologies could revolutionize the breeding industry, if given the latitude to be used. The precision associated with the technique results in better products, faster production and the ability to cater breeding to the needs of today’s farmer and consumer.