Watermelon is the iconic summertime food, but what are breeders doing to improve and change it?

Hot dogs, picnics and watermelon! These classic icons of summertime leisure are an integral part of childhood nostalgia for many. Enjoying a watermelon’s sweet, juicy taste provides a connection that takes us back to ancient Egyptian royalty and, according to Mark Twain, upward to the angels.

DNA detective work by botanists at the University of Munich in Germany confirms that the watermelons depicted on the walls of at least three ancient Egyptian tombs are in all certainty domesticated sweet, red fruits that were grown 3,500 years ago. In other North African countries, wild inedible watermelons with white flesh still grow.

Globally, watermelons are the third most popular fruit behind tomatoes and bananas, and in 2016, watermelon production totaled 117 million tons.

In the United States, watermelon is commercially grown in 44 states with the highest production in Georgia, Florida, Texas, California and Arizona. Nearly 6% of all land used for growing produce in the United States is planted with watermelon. In the United States, consumers overwhelmingly prefer seedless melons. Consumers in other regions have different preferences.

Watermelon Around the World

“Consumer preferences vary enormously around the world,” says Isabel Cayuela Zamora, head of crop marketing, Nunhems Netherlands BV. “Developed markets such as the United States, Europe, Australia, and Japan prefer seedless watermelon, and the trend is moving towards smaller sizes and fresh-cut options.

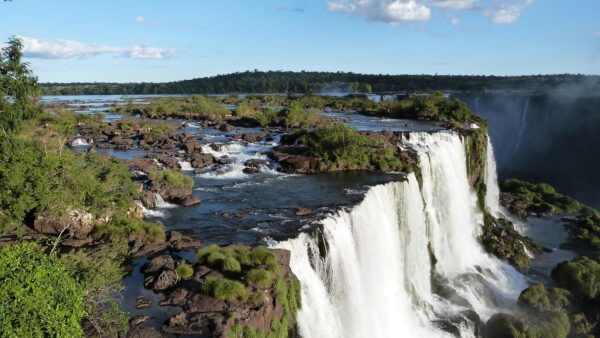

“Latin America is a traditional market where watermelons are still big and seeded. However, in the past few years we have seen seedless and smaller sizes entering into markets such as Brazil. India is a traditional seeded market. In China, you can find everything from seeded to seedless and from big and small sizes. An emerging trend is a preference for small/personal sizes watermelons even if they have micro-seeds or edible seeds.”

With watermelons, it universally comes down to shape and flavor.

According to Greg Tolla, retired vegetable breeder for Seminis Vegetable Seeds, shape preferences differ around the globe.

“In South America, all countries except for Brazil prefer a traditional, elongated shape watermelon. Brazil wants a round shape,” he says. “The smaller, round watermelon is also the winner in Europe. In Spain, for example, the preferred size is around 10-12 pounds, and smaller 5-pound watermelons are also produced. Towards the East, in Turkey, the preference is still for large, 20-pound melons. This is a recent trend as much bigger sizes used to be favored.”

About 15 years ago, there was a big breeding effort globally towards smaller size melons. Plant breeders thought it was going to change the market. However, the personal size never became more than 10% of the market. Bigger watermelons continue to be favored as they are relatively less expensive.

Regardless of size, consumers everywhere generally prefer sweet and flavorful watermelon with red flesh.

Sweet, Nutritious and Occasionally Very Large

Because watermelons vary greatly in sweetness, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has set fruit quality standards based on Brix, a scale of sweetness that is estimated by measuring total soluble solids using a refractometer.

According to the USDA 1978 Standards for Grades of Watermelons, edible parts of the fruit having not less than eight brix are deemed to be “Good,” while edible parts of the fruit having more than 10 brix are deemed to be “Very Good.” While there are hundreds of watermelon cultivars grown commercially in the United States with a wide range of sweetness, the sweetest watermelon is reported to be the Bradford variety. This legendary melon was a favorite of Southern growers and home gardeners in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These melons have a brix value of 12.5, nearly as sweet as apple juice.

“Watermelon is chief

of this world’s luxuries … When one has tasted

it, he knows what

angels eat.” Mark Twain

During the height of its popularity, sweet Bradford watermelon juice was routinely boiled into molasses or distilled into brandy for cocktails. Some growers would stand guard at night to prevent interlopers from getting a five-finger-special on this prized fruit. Eventually, commercial production of Bradford melons waned and ended in the early 1920s. Although its skin is quite thick, it is too soft to allow the melons to be shipped to market without damage. Now regarded as an heirloom variety, Bradford is being reintroduced by the original Bradford family that popularized the variety more than 150 years ago.

Some of the largest watermelons in the United States are on display each year at the Hope Watermelon Festival in Hope, Ark. These gigantic melons dwarf the commercial varieties sold in grocery stores and farmers markets. The Guinness Book of World Records reports the heaviest watermelon ever recorded in the United States was a 350.5-lb. melon raised by a Tennessee grower in 2013. Medium and large commercially grown melons sold in grocery stores range in size from 18 lbs. to 21 lbs.

Per capita U.S. watermelon consumption was estimated to be 15.8 pounds in 2018. Total watermelon consumption in the United States was estimated to be 5.2 billion pounds in 2018.

Our preference for seedless watermelons is a trend that began to take hold about 10 years ago. While watermelon is enjoyable as a refreshing summer staple, it also provides a nutritious punch. Each serving provides an excellent source of Vitamin C, a good source of Vitamin B6, and a delicious way to stay hydrated with only 80 calories.

Reflecting consumers’ changing preferences for lighter, more varied fare, watermelon items are becoming more popular in restaurants and bars. According to a recent study commissioned by the National Watermelon Promotion Board, watermelon on menus has grown by 54% in the past four years.

In 2018, Dutch vegetable breeding company, Nuhems, introduced Kisy, a sweet, personal-sized, easy-to-eat watermelon. Its deep red-colored flesh is easy to eat with a spoon as if it were an ice cream sundae. Its easy-to-eat properties also make it ideal to use for mixing watermelon cocktails.

“We were aware that young consumers are eating less and less watermelon as the fruit is perceived as inconvenient,” explains Hans Driessen, Nunhems plant breeder. “The goal was to develop a personal watermelon that can be eaten as one single portion, can be carried in your bag and can be a healthy and tasty option as a snack.”

Branding and marketing Kisy by variety is unusual in an industry where products are overwhelmingly marketed as a commodity. Unlike agricultural crops that are marketed and purchased by variety, the only differentiation consumers appreciate is whether or not a melon is seedless. The story behind seedless watermelons involves alterations to the plant genome itself through mutation breeding.

Watermelon Development and Seedless Watermelons

In 1939, plant breeders successfully developed tetraploid watermelon plants with four copies of each chromosome in each cell. When these tetraploid plants are crossed with ordinary diploid melons, the resulting melon plants were triploids with three sets of chromosomes. Triploids cannot produce seeds because their reproductive cells require an even number of matching chromosome sets. The result was “seedless” watermelons. What appears to be white seeds are merely empty seed coats, not viable seeds.

Maintaining the tetraploid parent lines by treating seedlings with colchicine is the most difficult part of producing seeds for a tetraploid watermelon. Because of the difficulty in maintaining the parental lines and the usual practices needed to produce hybrid seeds, seed for seedless watermelons is quite expensive, as much as $150 per 1,000 seeds. Because of the expense of the seeds, most tetraploid plants are started as transplants.

Germination of tetraploid seeds is usually not as good as standard cultivars, even under ideal conditions. A crop of seedless fruit involves the participation of melons with three different genomes. To increase the success rate of pollination, plant breeders have created diploid plants, which do not produce female flowers thereby reducing the chances of two diploid melons producing seeded fruits.

To grow the seedless watermelons preferred by consumers, a seeded pollinator watermelon with male flowers must be a companion to the seedless plants, whose pollen is not viable.

“Growers frequently use bees to facilitate pollination,” explains Greg Johnson, a University of Delaware Extension vegetable and fruit specialist. “Watermelons are a native desert plant. They like heat and tolerate dry conditions, but to obtain good melon yields, they require pollination and frequent irrigations.”

“Public plant breeders are usually focused more on prebreeding, and private breeders work more on cultivar development,” says Todd Wehner, Department of Horticultural Science at North Carolina State University. “Public roles are research and training. Private goals are cultivar release and sales support. Funding at NC State, for example, has shifted from federal Hatch support and funds from North Carolina to grants from the USDA and other groups. As a result, research has moved toward other high-value crops. Royalties are not easily obtained for most vegetable crops including watermelons.”

For plant breeders, flavor is a crucial goal of virtually every breeding program but not the only objective. A perfect-tasting variety without an effective fungal, virial, and bacterial disease resistance package will not be successful with growers. Functional commercial yield components, including shelf life and consistent fruit size are important to both growers and shippers. Private plant breeders continually develop improved varieties to assure that consumers everywhere will continue to enjoy flavorful watermelons and continue to “know what angels eat.”