Human history is intimately connected to the history of the plants and animals that we began to domesticate for our benefit 10,000 years ago, during the Neolithic. Now, researchers from the University College London (UCL), the Natural History Museum from the same city and the Centre for Research in Agricultural Genomics (CRAG) have succeeded in sequencing the DNA of wheat species that was harvested over 3,000 years ago in Egypt. The results, which are published this week in the journal Nature Plants, show that this wheat had already been deeply domesticated 3,000 years ago and that its genome is closely related to modern emmer wheats that are grown in India, Oman and Turkey.

The knowledge provided by this study will also have future applications.

As explained by CRAG researcher Dr. Laura R. Botigué, one of the main authors of the study, “characterizing the genomes of old samples will allow us to discover genetic diversity that has been lost in the current varieties, and recover genes that may have a high agronomic interest in the current climate crisis context.”

At CRAG, Botigué studies ancient DNAs from domesticated animal and plant species. In this case, the study sample was found in a collection of the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology at the University College London (UCL). Botigué and the archaeobotanist Dorian Fuller convinced the museum’s curator to let them extract DNA from some emmer wheat grains from an excavation in Egypt led by the archaeologist Gertrude Caton-Thomson in 1924. Thanks to the collaboration of Dr. Mark Thomas’ laboratory at the UCL Institute of Genetics they were able to extract a DNA of sufficient quality to sequence it and make subsequent analyses.

The researchers note that the specimen was stored for over 90 years without any climate control.

“Importantly, material excavated over 90 years ago and since then stored without climate control can yield usable DNA, which accentuates the great potential of museum specimens for genetic analysis,” says senior author Richard Mott, UCL Genetics Institute.

Petrie Museum curator Anna Garnett, adds: “This study shows that our collection is a dynamic and living resource. Genetic data allows us to look at these specimens from an angle that couldn’t have been imagined when they were first added to the collection.”

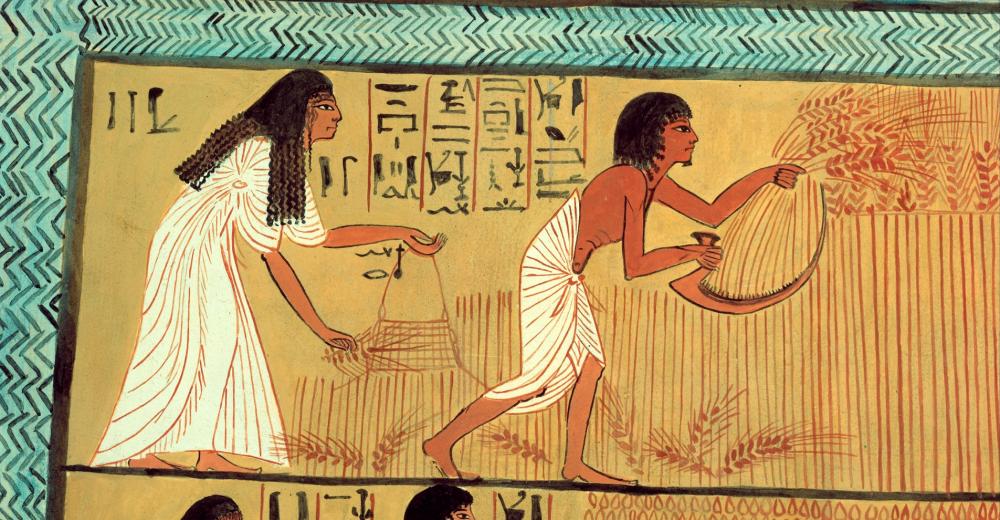

Emmer wheat (Triticum turgidum subsp. Dicoccon) was the most popular cereal in ancient Egypt. When the Romans invaded Egypt they adopted the use of this cereal, which they called “Pharaoh’s wheat” (“farro” in Italy). Most wheat grown today is bread wheat, which is the result of a hybridization between emmer wheat and a wild grass. To further complicate matters, emmer wheat is itself the result of an older hybridization in the wild.

The study now published in Nature Plants also found signatures of pre-historic human activity in the ancient wheat genome.

“Wild emmer wheat seeds are released from the plant where they can’t be easily harvested. Under cultivation, deliberately or coincidentally, farmers bred emmer wheats that retain their seeds. This specimen was domesticated, likely over 8,300 years ago based on archaeobotanical data, and would have retained its seeds,” explains Fuller.

The comparison of the DNA of this emmer wheat from 3,000 years ago with the genome of modern varieties of the same cereal that are currently grown in India, Oman and Turkey, has led researchers in London and Barcelona to hypothesize that once domesticated in Fertile Crescent region of the Near East, the cereal dispersed in various waves. A first wave would have run along the north Mediterranean coast and Europe, and a second wave would have gone to Africa and Asia.

“This result is surprising, since it was traditionally assumed that the Neolithic period extended in parallel along the two coasts of the Mediterranean, and instead this ancient emmer wheat is telling us another story,” says Botigué.

Although the process of plant domestication has led us to enjoy crops that provide the necessary nutrition, in this process we have lost a large part of genetic variants that could be useful in the future, especially in the context of climate change. Recovering this genetic variability is a key objective for the plant breeding sector.

“We observe that old varieties show unique patterns of genetic variability that modern plant varieties do not show,” explains Laura R. Botigué. “Recovering this genetic variation from the past will be a very valuable tool for current crops,” adds another author from London.

In this sense, emmer wheat will be a cereal to be studied: it is resistant to certain pests, and is capable of growing in impoverished soils and with scarce water. So far, one author of the study has already baked his own bread using modern emmer wheat.