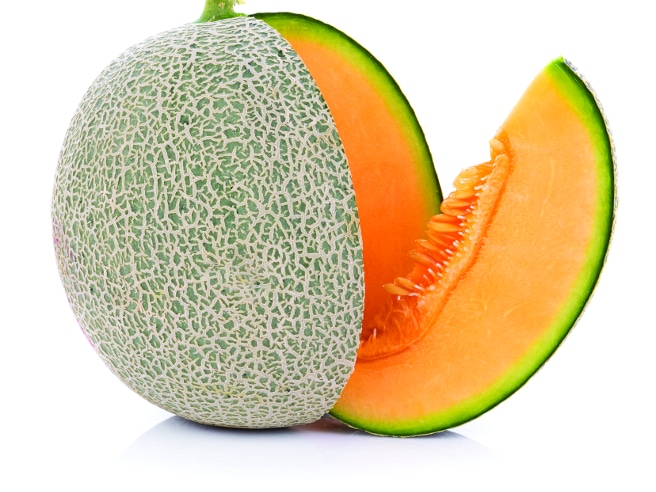

We’ve all been there. You buy a supermarket cantaloupe, cut it up, take a bite, and start chewing. You’d hoped for a juicy, succulent, flavorful fruit, but instead the experience is akin to trying to eat a piece of wood. One that kind of, sort of tastes like cantaloupe.

Lack of flavor in supermarket varieties of melon and other cucurbits is a hot topic right now in the breeding community, so much so that a keynote speaker at the recent Cucurbitaceae 2018 conference at the University of California, Davis on Nov. 12-15, 2018, was someone for whom bringing the flavor back to supermarket cantaloupe has been a major project.

Victor Verlage, senior director of resilient sourcing for Wal-Mart, delivered an opening address that focused heavily on working with the seed community to deliver new varieties of melon to consumers. A big focus of his talk was the Sweet Spark cantaloupe, developed by Walmart and Bayer, and now sold in over 1,300 U.S. Walmart stores.

Sweet Spark is sweeter than other cantaloupe sold at the supermarket. While regular melons have excellent shelf life and growers like them because they yield well and are disease resistant, they can be lacking in the flavor department, Verlage notes.

“For the past 15 years, cantaloupe has been losing ground among our customers. Year over year, our cantaloupe sales continued to decline,” he said. “Consumer insights show that product attributes, especially flavor, need to change in order for Walmart customers to start buying cantaloupe again. We need to delight palates.”

Enter the cucurbit research community. The hunt for new genetics that get turned into varieties like Sweet Spark is heating up, and cucurbit researchers and breeders are positioned to deliver on what the marketplace is after by “bringing back” the flavor to cucurbits like cantaloupe.

But alas, it’s not an easy task. Sweet Spark was years in development, and varieties like it don’t typically come with the sky-high yields, ease of harvest and long shelf life of traditional supermarket varieties.

“Flavor in vegetables used to be much more common in heirlooms, because individual people were much more engaged in the whole breeding process, saving seed from what they enjoyed. But, as agriculture has gone to its global model and we have developed these commodity classes, that’s constraining the diversity that’s there,” says Michael Mazourek, vegetable breeder at Cornell University who sat on the scientific committee for Cucurbitaceae 2018.

“Once you constrain the diversity, there is only so many things you can select for in a breeding project. If you remove those constraints — not worry so much about size or shape or shelf life — you’re free to focus on other things, like flavor.”

That philosophy has led to the creation of Row 7 Seeds, a partnership between Mazourek, seedsman Matthew Goldfarb and chef Dan Barber (author of The Third Plate), which bills itself as “a seed company built by chefs and breeders striving to make ingredients taste better before they ever hit a plate.”

Seven years ago, Barber challenged Mazourek to build a better butternut squash. For Mazourek, it was the first time that someone had asked him to breed for flavor. For Barber, it was the discovery of a new kind of recipe — one that begins with the seed.

New Tools

Mazourek is active in the Cucurbit Coordinated Agricultural Project (CucCAP), which was a big focus of Cucurbitaceae 2018. The CucCAP is a U.S. group that works to leverage applied genomics to increase disease resistance in cucurbit crops. Most recently, CucCAP research identified a cucumber gene for resistances to downy mildew, angular leaf spot and anthracnose.

The CucCAP involves 21 different research groups working to improve disease resistance in watermelon, melon, cucumber and squash using the latest tools. They do this by scouring the globe for germplasm that contains disease resistance that can be used to breed new varieties that producers want to grow and consumers want to eat.

“One thing that new genomic tools can help us do is identify regions of the genome that have the genes with resistance and make use of those regions, and not the others with traits we don’t want,” says Rebecca Grumet, horticulture professor at Michigan State University and the CucCAP’s lead researcher.

The CucCAP is also helping get cucurbit disease information out to people in the wider community. Angela Linares, associate director of the Department of Agro-Environmental Sciences at University of Puerto Rico, has translated a number of CucCAP fact sheets into Spanish, an effort she says will help bolster food security on the Caribbean island of 3.3 million people and elsewhere in the U.S.

“The CucCAP presents a unique opportunity to reach other communities, not only farmers but employees, students, or anyone else who wants to learn about cucurbits,” Linares says. The cucurbit community at large is no stranger to reaching out in order to solve problems and create improved varieties, notes Allen Van Deynze, a Canadian plant breeding researcher based at UC Davis and an organizer of Cucurbitaceae 2018.

“We are a mixture of geneticists, plant breeders, pathologists, agronomists and so on. It’s quite an international community,” he says.

“There’s a lot of potential. Cucurbits are really a young crop breeding-wise. When I grew up in Canada there were three melons you could get: watermelon, honeydew and cantaloupe. And that was it. The genetic diversity within each of these is incredible and it’s untapped. If you travel around the world, it’s like, ‘Whoa, this tastes fantastic. Why isn’t this on my shelf?’”

Breeding for the Shelf

Vegetable seed company HM.CLAUSE, a major sponsor of Cucurbitaceae 2018, does just that. That quest for new genetics that can be turned into new products is what excites Bill Copes, HM.CLAUSE cucurbit breeding coordinator based in Sacramento, Calif.

“We spend a lot of time in the field tasting these products, looking for something that’s unique, looking for something that’s a little bit different that might have a little higher flavor profile,” he says.

Like the Bayer/Walmart collaboration, HM.CLAUSE has partnered to develop the Origami cantaloupe, which features improved flavor characteristics. Copes notes that varieties with improved flavor usually come with a trade-off for growers, like lower yields and more frequent harvests, so while Origami has been a hit with many consumers, the cantaloupe market won’t be revolutionized overnight.

Still, as researchers learn more about cucurbit variety development through groups like the CucCAP, the future looks promising.

“For growers who are willing to grow a product like Origami, I think there’s a lot of opportunity. But, there’s still going to be, in my mind, a large percentage of growers that really just want the simplicity of growing a Harper melon. The achievable goal is to combine high flavor with good yields and harvest management.”

The quest for new varieties of cucurbits with sought-after characteristics also extends to other vegetables like cucumbers.

“In Israel we have the Beit Alpha cucumber, which is a very smooth skim, not warty, not bumpy, fruit. That’s definitely got to be my favorite. They’re very expensive in America. What I usually buy in the U.S. is the English Hot House type, the really long greenhouse cucumber. That’s the closest I can get to what I want from home,” says Ben Mansfeld, PhD student in Grumet’s lab at Minnesota State. He hails from Israel and is researching the developmental trait of age-related resistance (ARR) to Phytophthora capsici in cucumber.

“We are starting to get more interest in the United States in other types of cucumbers, and I think that will drive more and more of the seed companies and breeders to develop more lines that can be grown here.”

New cucurbits resources online

Some new websites have been launched that offer some important resources to people working in cucurbits.

cucurbit.info — The Cucurbit Genetics Cooperative (CGC), established in 1977, provides services for researchers interested in the genetics and breeding of species of the Cucurbitaceae crop family.

cuccap.org — The objective of the Cucurbit Coordinated Agricultural Project (CucCAP) is to leverage applied genomics to increase disease resistance in cucurbit crops. This site provides extensive information regarding cucurbit disease detection and control in both English and Spanish, and is linked to the new cucurbit genomics website, cucurbitgenomics.org

cucurbitgenomics.org — The CucCAP project has allowed for development of a fully revamped cucurbit genomics website providing a central portal for the cucurbit research and breeding community including up-to-date genome sequence, gene expression data, genetic maps and genomic analysis tools for cucurbit crops.