With the capacity researchers now have to generate and analyze big data, study areas like metabolomics are becoming more accessible to smaller labs. Seed research is becoming democratized, with more and more researchers having access to technologies and data that were once the purview of better-financed labs.

We’ve approached a decisive point in the field of seed science. We’re on the verge of making huge strides in our understanding of what goes on inside a seed, and it’s no understatement to say every person on earth stands to reap huge benefits. As humans, we’re protecting that energy source for our own use (food) through a deeper understanding of seed biology.

To really be successful, the agriculture science community needs to continue to come together and rally around seed in a way that helps brings all disciplines together with one goal in mind —advancing knowledge of seed.

Big data represents a tsunami of information permitting insight into problems in seed biology; an overview of what’s going on in a variety of biological pathways simultaneously. We now have a capacity to step back and look at the broad scope of various areas of interest — like the above-mentioned metabolomics which looks at unique chemical fingerprints and the culmination of specific cellular processes — pointing to what’s going on inside the seed to allow these processes to take place.

A seed survives the loss of most of its water, and then upon hydration, kick-starts metabolism — an almost miraculous process. How does it work? How can you possibly lose that amount of water and live? Seeds do it — and we possibly have a handle on some of the molecules permitting survival.

If you like to eat, you’re highly invested in seed biology. Seed represents 70 percent of our food. Much of the remaining 30 percent is made up of animals that we feed seeds to and fruits/vegetables that are started from seed. The capacity to store these seeds in a dry state allows us to ship food in that state worldwide.

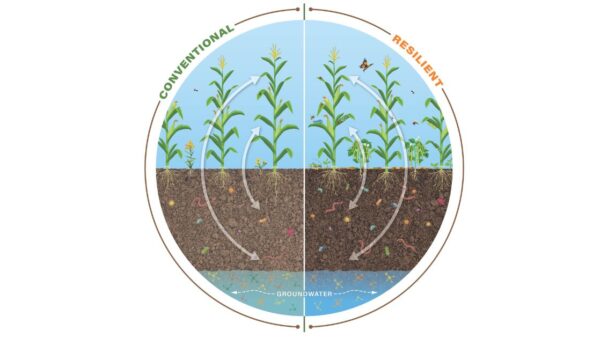

Farmers are at the forefront of the world food stage making that happen. To grow food, they have to purchase seed from seed companies. That cost has risen as we stack more and more desirable traits in the seeds. Seed companies have an obligation to supply seeds that offer a very high percentage of germination under a variety of different weather and environmental conditions.

The farmer won’t be happy if the seeds they spent so much money on don’t complete germination. Seed companies incur a huge expense trying to generate highly vigorous seeds each year so farmers are guaranteed high germination percentages.

That’s where strides in seed storage come in. Right now, seed is generally grown every year for sale that same season. We hope that if we can show seed companies that you can store seeds for a long period without any negative effect on quality, that we can transform the current model of seed production and make quality seed even more widely available globally.

Imagine seed companies having one production year, and being able sell those seeds for a few years after without having to produce any new seed. They would realize a huge cost savings, at the same time keeping the farmer happy because the seeds’ vigour didn’t decline. Talk about a win-win for everyone.

Any plant biologist nowadays working on a crop plant or trying to get better product to market is, in fact, a seed biologist. Groups like the International Society for Seed Science, of which I’m a proud member, are working to advance the interests of seed science with the goal of a better world.

If you’re in pathology, you’re protecting the crop from being eaten by pests that otherwise reduce the amount of photosynthate available with which to make seeds. If you’re into studying root development, a major reason you’re getting money to do that research is because it ultimately means more seeds for humans to eat.

Seeds have been changing the world for thousands of years, and will continue to do so in increasingly profound ways. Continuing to make progress in this area requires us to remind ourselves how the march of technology is creating a level playing field in the research community. We are all directly invested in decoding the biological mystery that is seed.

—Downie hails from Nova Scotia, Canada, where he completed his bachelor of science in biology at Acadia University. He obtained his PhD in botany at the University of Guelph.