A University of Nebraska-Lincoln lab has found that microbes living in soil affect the way plants grow in certain conditions, such as drought or high PH levels.

The Root and Soil Microbiome Lab conducted field research and controlled studies of plants and microbes to determine their mutual effects on each other.

“There is a whole other world in soil,” graduate research assistant Morgan McPherson says. “The interactions between the microbiome and plants growing in the soil is so immense.”

Plants are also able to affect the microbes found in their roots and the surrounding soil. According to Daniel Schachtman, director of the Center for Biotechnology and founder of the lab, plants exude substances such as hormones, amino acids and proteins, which can affect the surrounding soil’s microbiome, or mini ecosystem of microorganisms.

Schachtman and his team focused on understanding how plants control their microbiomes and how the microbes affect plant growth. Abiotic stress factors such as drought or high PH soils can slow plant growth. With certain microbes present, the plants are able to avoid these negative effects of abiotic stress.

The lab’s research began with descriptive studies about the changes in root microbes in conditions with high levels of CO2 and ozone gases. Since then, Schachtman has performed more descriptive field studies that “take census” of plants and their microbiomes in various conditions. During these studies, he and his team also gather microbes for its collection of 3,600 unique microbes.

Through these descriptive studies, Schachtman has built a foundation of knowledge from which he can start testing more specific hypotheses. With the collection of 3,600 microbes, the lab can test certain microbes in controlled conditions in order to measure their individual effects on plant growth.

“Say, for example, this microbe is more abundant under drought conditions,” Schachtman says. “What’s its function? What is it doing there? Are all the other microbes just dying or is this one something that is useful to a plant?”

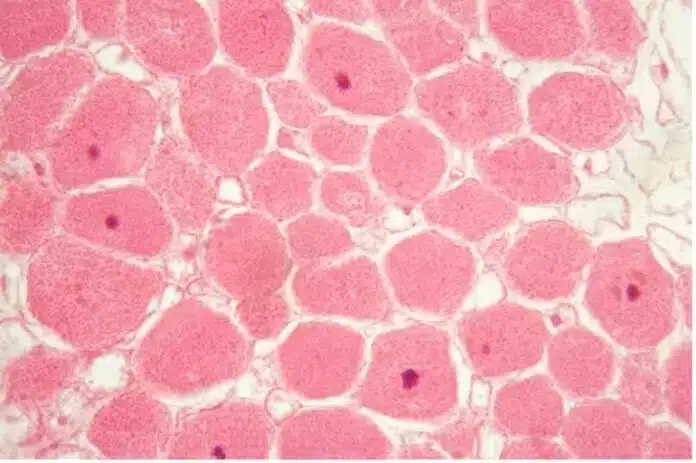

One such study of specific microbes involved growing them in isolated plates in order to see if they could produce their own nitrogen. By isolating the microbes from soil and plants, the researchers can begin to understand the current unknown functions of microbes.

According to Schachtman, microbes in the human stomach have been studied extensively for the past 15 years, but still, not much is known about the interactions between microbes and plants. Through his research, Schachtman is attempting closing this gap in knowledge.

Schachtman and his team are also studying the secretions of hormones, proteins and amino acids that plants exude during abiotic stress. In one project, 400 corn lines are planted into tubes of glass seeds, and the roots are soaked in alkaline solution for a few hours at a time.

The corn roots’ secretions are then drained out and measured. Their composition can help the researchers understand the root’s reaction to stress and how this reaction could affect the surrounding soil’s microbiome.

McPherson is also testing her own hypotheses in two independent experiments run through Schachtman’s lab. The first tests the response of soybean plants and the surrounding microbes to alkaline soil in agricultural fields. The second experiment gathers native plants and microbes in various levels of alkaline soils in Nebraska’s sandhills ecosystem.

In both experiments, McPherson processes her soil and root samples for DNA sequencing. She then uses DNA sequencing data to come to conclusions about the experiment.

With the lab’s research, Schachtman says he hopes to find ways to prepare the agriculture industry for stresses such as drought and low nitrogen in soil. By understanding which microbes help plants grow, the researchers could find microbes that would help plants in times of stress.

“If we can find some [microbes] that help a plant acquire nitrogen, maybe a farmer could apply less nitrogen to their fields,” Schachtman says. “That would cut costs but also reduce pollution in the water table.”

Moving forward, Schachtman says he also hopes to test more specific hypotheses with more samples for a higher level of accuracy. He is also considering testing phenotypes and working with drones in the field.

“We want to understand whether [microbes] have no beneficial or detrimental effect on the plants,” Schachtman says. “Or whether they’re protecting the plants against drought, for example. That’s what I’m really interested in the end: trying to understand what these things are doing in the soil.”

Source: The Daily Nebraskan