Farmers are increasingly embracing a new digital reality, but the transition hasn’t been easy. Perhaps the most sensitive issue is farm-generated data, which raises a number of questions. Who owns the data? How can privacy be assured? Who benefits most from its use?

“Big Data” is a term that’s thrown around so much, it has almost become cliché. One might expect such an oft-discussed concept to be better defined. Yet, it really isn’t, and the ambiguous terminology might be stifling progress. It’s worthwhile to speak more precisely on just what we mean by “data.”

If we think about commodities such as crude oil, the value is not in the raw materials but in the refined products — the gasoline that powers vehicles. The same principle applies to information gathered in crop production, but let’s be specific about what is collected.

While managing their fields, many farmers amass contour maps of their growing environments and keep records of the weather, rainfall and water availability. They track soil conditions for their region and information on pathogen, pest or disease outbreaks. These can be called “historical geographic” data.

In addition, precision equipment and remote-sensing technology generate a wealth of information. Kept by either the farmer or the service provider, these records include chemical grids, soil classification maps, chemical and fertilizer application logs, historic crop and variety use notes, harvest monitor information and yield performance tables. These data can be called “production specific” data.

Finally, we have “ongoing environmental data.” These are the big-picture sets of information, such as satellite and weather images, forecasts and records. Governments typically collect crop yield information on a national level, but this data offers insight as to how farms perform on a regional basis. Other industries, such as finance and insurance companies, might also record similar information that may overlap with data collected by the farmer about individual fields.

In the rush to capitalize on big data, the historical geographic data tend to be forgotten. This information can be difficult to capture in an easily usable form, especially when competing data collection systems don’t play well with other systems. This information also lacks the appeal of the impressive satellite imagery or the usefulness of production-specific data.

But what happens when farmers gain access to more and better historical geographic data? When collected on their own, historic paper records just take up space. Even digitized data about a given field’s soil conditions over a handful of years offers limited insight.

Now imagine a whole suite of records about an individual farm, rigorously gathered year-after-year and recorded with precision. Such data contains a much greater value, because it’s now possible to spot anomalies in long-term records.

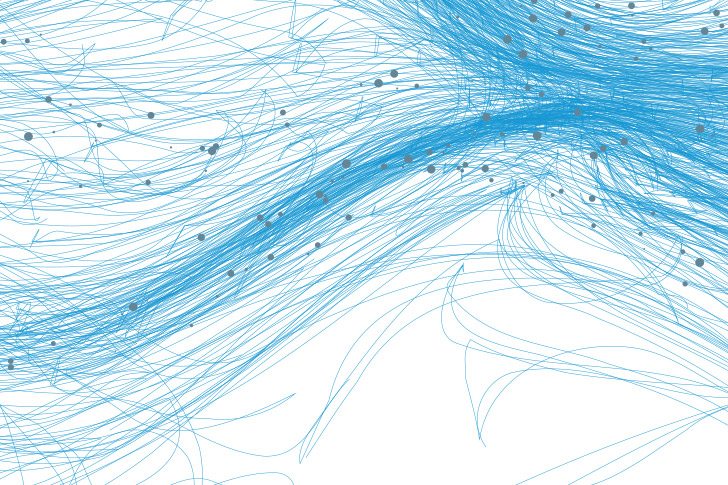

The true utility, however, comes when data analytics and algorithms process and convert the information into an easy-to-visualize form. For instance, the yield of individual plants in a particular field can be measured and converted into a map. Areas of lowest growth, colored in red, immediately stand out, alerting farmers to problems in need of investigation. Perhaps the irrigation isn’t reaching part of the field, or there is some other mechanical problem. This allows small problems to be solved before they become a yield-destroying crisis. This is how properly refined data can create value, by providing farmers a competitive edge through risk mitigation.

Of course, it’s no secret that every player in the value chain has an interest in farmers’ data. Seed producers want to see how their varieties stack up against the competition. Scientists want to track trends that affect crop performance. Governments want to monitor big-picture production numbers that affect trade.

It’s easy to assume that out of these competing interests, the farmer is being left behind, but that’s not so. In every part of the value chain, the availability of more accurate historical geographic data improves products. Seed companies will make better products, and farmers will receive better advice about placement and management techniques. Ultimately, higher quality data mean better harvests and more profit for farmers.

But a great deal needs to happen before we will see improvement in the flow of information across the value chain. Remote-sensing equipment needs to become cheaper and easier to use. Data standards have to encourage better communication. Open data initiatives are working on these standards and encouraging transparency among industry players. The industry is also working to address the data privacy, ownership and security issues.

All of these steps bring us closer to the point where farmers and industry will be comfortable in harnessing the commoditized data that will drive innovation to the next level, and farm productivity and profitability to new heights.