Companies see great potential in gene editing technology.

“Coming to a produce aisle, farmers market or dinner table near you!” When might this tagline ring true for the next generation of vegetables that bear traits developed through gene editing?

It’s hard for anyone in the production of fresh produce to not be excited at the prospects gene editing holds. From disease resistance and better storage quality to enhanced nutrition and stress resilience, this technique is expanding the advanced breeding playbook. Additionally, the U.S. Department of Agriculture ruled last year that gene edited plant material doesn’t need to endure the same regulation as crops containing

genetically modified organisms (GMOs).

The work of researchers has already resulted in a varied salad bowl of improved vegetable crops, such as mushrooms, cabbage and tomatoes, but those crops have yet to cross over into commercial production.

Although it holds much promise, there’s also the risk that this valuable tool could be quashed if consumers choose to lump it in the same category as transgenics.

Many companies recognize the advantages gene editing has to offer, but each is adopting a different approach when it comes to bringing this kind of product to market.

New Potato on the Horizon

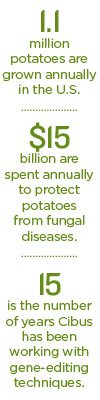

“Potatoes are one of the most widely grown specialty crops in the United States, with 1.1 million acres grown annually, produced on farms stretching across all 50 states,” he says. “At the same time, more than $15 billion is spent each year by farmers seeking to protect crops from the damage caused by fungal diseases.

Therefore, there is a huge market need for potatoes that can reduce fungicide use.”

The company’s potato research looks at other quality traits, such as resistance to black spot bruising. “Potato growers are quite interested in agronomic traits like weed control and disease control along with quality traits which allows them to maximize their profitability. Lowering the use of fungicide and other pesticides is also quite interesting to most growers as they understand most consumers prefer crops grown in an environmentally friendly manner,” Radtke notes.

Producers welcome these developments, in part, because the industry has been devoid of trait development for some time, the company believes.

“Since genetically modified potatoes are not acceptable in many countries, the potato industry has been deprived of new traits that have been developed in other crops using transgenic methods. Cibus’ RTDS technology offers a non-transgenic option to develop traits in potatoes.”

Radtke says Cibus is confident their potato can find success at the commercial level.

“Cibus has an advantage over other gene editing companies because of our experience with the entire process of developing a new trait in our lab, confirming the trait value, moving that trait to elite genetics and actually selling to farmers,” he says.

Cibus’ RTDS technology goes beyond other gene knockout techniques by making “targeted spelling changes to develop novel traits” that aren’t possible through other means, Radtke adds.

“It delivers exactly what we expect — precise targeted changes to genes.”

— James Radtke

But Cibus isn’t the only company taking advantage of new plant breeding innovations. Corinne Marshall of Sakata Seeds, a global producer of vegetable and flower seed, adds it could really benefit growers plagued by pest and disease.

“Viral disease transmitted by insects can be a huge problem,” she says. “Fungal pathogens in the soil such as Verticillium and fusarium are also quite problematic. Downy mildew in spinach, bacterial leaf spot in peppers and tomatoes — those are just some of the many disease and pathogen problems that we are facing.”

Marshall shares that the conventional solutions have been chemical control, which can be applied when needed and can address multiple issues. However, she said that it really restricts companies from the organic market and there are environmental risks associated with use, as well as additional costs.

“Other ways we’ve tried to better manage these issues is to build the resistance into varieties and not be restricted to playing the organic market,” Marshall says. “But the problem with that is we deal with very specific races and specific diseases and the cost can be quite expensive.”

Marshall uses Downy mildew in spinach as an example. “The demand for organic spinach exploded in the early 90s,” she says. “Since that time, we’ve been challenged with trying to come up with ways to deal with the problem, and we are basically chasing resistance and the races pop up annually.

“The future of organic spinach production is questionable. How long are we going to be able to keep up with the challenge of dealing with the resistance and come up with ways to handle that? Gene editing could provide the solution to having the stronger resistance to Downy mildew in spinach.”

Marshall says gene editing can be used to enhance nutrition in many vegetables, so it goes beyond just dealing with disease and pathogens. “This is a very exciting prospect,” Marshall adds. “Lycosine and glucosimulates in broccoli, which can reduce chronic disease or slow disease such as cancer; Sulphurephane is a glucosimulate in broccoli and most us know that when we cook the broccoli, we lose the nutrient. So gene editing can actually help us solve that problem.”

Consumer Acceptance?

It’s obvious that gene editing could tackle many significant issues for growers, but can it overcome perceptions among consumers who don’t like the thought of scientists ‘tinkering’ with nature?

Organic production prides itself on not using genetically modified plant material, but with the downy mildew problems experienced by spinach growers, might they embrace edited varieties?

As a company that’s been doing gene editing for the last 15 years, Cibus leaders say they have no doubt in the safety of this advanced molecular tool. Radtke says Cibus was pleased with the USDA’s ruling in 2015 regarding gene editing. “It delivers exactly what we expect — precise targeted changes to genes,” he says.