As research and development into the advancement of leafy greens has increased so has the level of intellectual property protection — and with that comes confusion about what can, and cannot, be done.

King of the vegetable industry, lettuce production in 2015 was valued at nearly $3 billion, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Agricultural Statistics Service. As a crop’s value increases, so does the investment in innovation and technology associated with the crop.

Seed companies have been adding value to lettuce, helping it to overcome biotic and abiotic hurdles and insect and disease pressures, all while increasing yield and meeting consumer demands. To make this happen, companies have poured millions of dollars into research and development and breeders have toiled over research plots, analyzing data and selecting the best varieties to move forward in their programs.

“We spend around 25 to 30 percent of our turnover in research and development,” shares Rick Falconer, who serves as managing director of Rijk Zwaan USA.

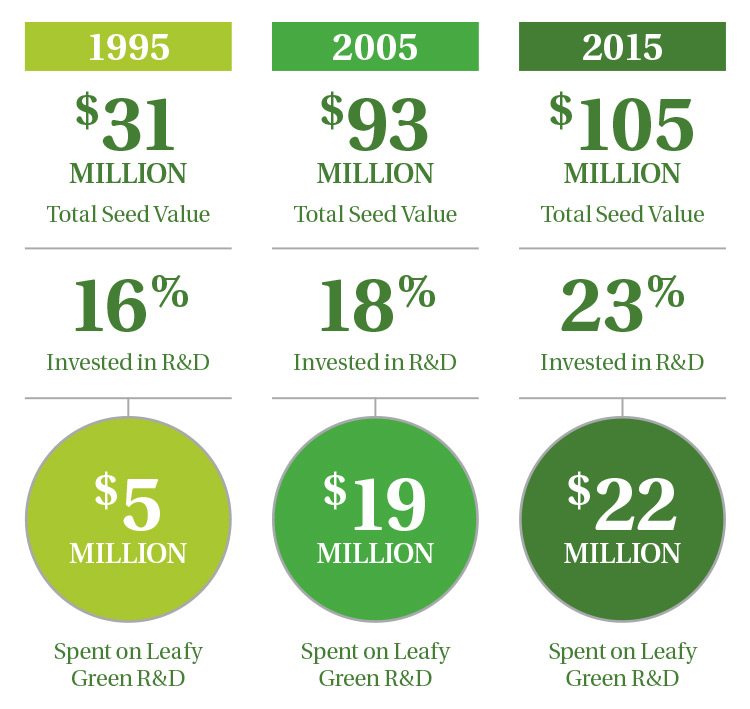

It’s estimated that the seed industry as a whole invested $5 million on leafy green research and development in 1995, according to figures from the Seed Innovation and Protection Alliance (SIPA). Today, that number is closer to $22 million.

As such, companies and plant breeders want to protect their investment. “Intellectual property (or IP) is the vector of innovation,” shares John Schoenecker, HM.CLAUSE director of intellectual property. “Every year, we create many new varieties. There are IP concerns throughout the entire cycle of plant variety protection, which includes innovation, breeding and distribution.

“In innovation, legally accessing or protecting technologies and novel traits of interest to growers and consumers is important. In breeding new varieties, IP allows us to balance the protection of new varieties while facilitating access to genetic diversity. In distribution, IP secures our return on investment.”

Playing by the Rules

Falconer explains that to remain healthy as a business and as an industry, “it’s important to earn a return on investment, which can then be reinvested in research and development activities.”

Plant varieties can be protected by many forms of IP, some of which include plant variety protection (PVP), agreements, trademarks, copyrights and trade secrets.

When it comes to lettuce and leafy greens, there’s a patent that will be expiring this spring. So what can a company do, or more importantly not do, to prepare for the expiration of this coveted patent and take advantage of market demand?

The answer: “It depends,” says James Weatherly, executive director of SIPA, which was formed in 2014 to create a unified and consistent voice for education and best practices around IP protection and its value. “You have to read the patent to find out what is, or is not, permitted in the 20-year period of protection.”

He says a patent doesn’t just restrict sales, but can also prohibit research, breeding and multiplication prior to an event’s expiration. For instance, a patent with the appropriate language can prevent companies from working with the patented material before the patent expires.

“In most cases, depending on what the patent actually says, you can’t breed, produce or save seed until the patent expires,” Weatherly says. “Just because you are not selling the seed doesn’t mean that you are not infringing.

“Just because you are not selling the seed doesn’t mean that you are not infringing.”

— James Weatherly

“This also includes breeding work outside of the United States. That seed can’t be imported or exported prior to patent expiration.”

To help interested individuals understand what is covered under a patent, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office makes this information available on its website.

Weatherly says that claims can be made to germplasm, methods used to produce germplasm and more.

If someone, or a company, infringes on a patent or PVP before its expiration, they can be liable for paying damages and royalties, in addition to seizure or destruction of infringing crops. “There can be major consequences to conducting activities prior to a patent’s expiration,” Weatherly says, including the cost of litigation.

Weatherly says the risks of IP infringement far outweigh the rewards. “The rewards are short-term gains,” he says. “The cost of litigation for patent infringement can run upward of $600,000. Plus, and maybe most importantly, is the damage to a company’s reputation.

“It’s a small industry and word gets around quickly. You don’t want your name to be mentioned, or to come to mind, in discussions of bad business practices.”

Falconer adds that if PVP in crops, such as lettuce, is commonly compromised, “without a doubt, you will see innovation slow.” Yet, he says there is more and more demand for solutions to challenges such as insects, disease, waste and limited labor. “If we are to stay ahead of these issues, it needs to make good business sense,” he says.

Weatherly advises companies and breeders to take the time to know their rights and the rights of others before jumping into anything. “Do your due diligence beforehand and talk to a seed dealer, check the bag tag and tag labeling, refer to the limited use/technology use agreement, consult the seed company website and contact the seed company,” he says.

Falconer acknowledges that playing by the rules can be complex. “Companies need to have a robust and thorough IP system, not just to protect their own innovations, but also to respect the IP of others,” he says.

To help those in the seed industry better understand the intellectual property associated with plants, SIPA hosts technical education units throughout the year. The next event will be held Jan. 29 in conjunction with the American Seed Trade Association’s annual Vegetable & Flower Seed Conference in Orlando, Fla. Learn more at seedipalliance.com.

“Just because you are not selling the seed doesn’t mean that you are not infringing.”

“Just because you are not selling the seed doesn’t mean that you are not infringing.”