Experts estimate hybrid wheat will be on the market within 10 years. What can the seed industry and farmers expect?

It seems hybrid wheat’s time has come.

“It’s the new step-change in technology, and if there’s a company to do it first, it’s Syngenta, due to our germplasm pool and the knowledge we have,” says Darcy Pawlik, cereal product manager for Syngenta in North America. “It’s all about making wheat competitive with other crops including corn, soybeans and canola. We’ve done a lot of homework, and there’s a great story to tell with hybrid wheat.”

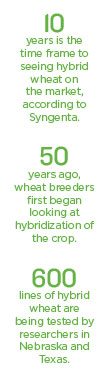

Pawlik spoke at a recent Syngenta media summit in North Carolina about hybrid wheat, where Syngenta staff suggested the company will have the product available and on the market for growers in the next several years.

It’s that kind of enthusiasm that those in the wheat industry eagerly anticipating a new era in one of the world’s most planted cereal crops. As corn and soybeans have overtaken wheat in terms of acres in the United States, the industry is thinking of ways to bring wheat back as a major player and give growers the benefits it believes will come with that change.

“As time evolves, my expectation is you’ll see the wheat hybrids, with continued investment, become more common and more valuable,” says Stephen Baenziger, professor in the Department of Agronomy and Horticulture at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln. He agrees the 10-year time frame to seeing hybrid wheat hit the market is about right.

Baenziger is part of a research program working toward the development of hybrid wheat varieties. Also involved is Amir Ibrahim, a Texas A&M AgriLife Research wheat breeder. Ibrahim has been working on hybrid wheat since 2013, but wheat breeders first began looking at hybridization in wheat more than 50 years ago in the early 1960s.

“The price for wheat was so low, and the cost for the hybrid seed was too high at the time. Today we have a better handle on the genes and better prices and availability of genomic tools,” Ibrahim says.

Under a Monocot Improvement Initiative grant from AgriLife Research, as well as funding from the Texas Wheat Producers Board, Ibrahim is working with the University of Nebraska, Lincoln to test more than 600 lines of hybrid wheat in Nebraska and Texas.

The performance of the varieties of wheat developed by AgriLife Research’s wheat breeding team has been improving across the state and into other states with diverse climates, providing a solid base of germplasm.

Changing the Face of Wheat Farming

“Farmers have to see a yield increase with hybrid wheat,” Baenziger says. “No farmer’s going to buy hybrid wheat seed if it doesn’t offer that.”

Ibrahim says that by using next-generation sequencing technology, they may be able to select for performance traits that can result in higher biomass and yield, drought tolerance, consistent performance, quality, disease resistance and agronomic adaptation, vigorous root system and increased production in low-fertility conditions.

Wheat production yield potential has been leveling off and “this is one way to break that barrier,” he notes.

Along with increased yields comes the potential for less reliance on fungicides and herbicides, Baenziger notes.

“Instead of having one variety that must have all your disease resistances in it, you can get some from one parent and some from another, and the hybrid will be more resistant. You might see lower fungicide costs as a result. On the herbicide front, you might see a hybrid crop display early vigor and crowd out the weeds, so fewer herbicides is possible.”

Pawlik notes hybrid wheat plants aim to be hardier than their non-hybrid counterparts.

“You’ll see more above-ground biomass, but what goes on above ground also goes on below. We see larger biomass of roots, which allows better accessibility of water and nutrients, and the plants will better sustain droughts and waterlogging,” Pawlik says.

But, Baenziger adds, farmers may actually choose to invest more heavily in crop protectants when planting hybrid wheat. “Seeing as hybrid wheat will be a more valuable higher-yielding crop, you could see more fungicides and pesticide used to ensure you’re able to actually capture that higher yield.”

That’s because farmers will see the value in hybrid wheat and, as seen with hybrid corn, they’ll want to do everything they can to protect that investment. That, of course, means opportunity for companies producing seed and crop protectants.

“Within five years, I hope we can have the first commercially available hybrid seed available for producers.”

— Amir Ibrahim

Price Matters

Naturally, hybrid wheat will be more expensive than varieties currently available, Baenziger says. Ibrahim notes hybrid seed must be bought each year due to inbreeding depression and dilution of vigor associated with growing saved seed, so producers cannot save their seed and replant, as is commonly done now.

“With hybrid wheat, you’ll see it go from 30 percent certified seed to virtually 100 percent,” Baenziger says. “That will drive a whole series of changes in the industry.”

“Hybrid wheat will have to be more expensive, since there’s more labor and research cost involved, but seed companies could reduce the premium they expect to get to ensure it gets into the market. Then, once the growers see its true value, increase the price.”

Baenziger says this might come with some initial pushback, but it won’t last long.

“Growers often ask, ‘What’s the price?’ The real question should be, ‘How does it change my profitability?’ Once they see the value, they’ll be less concerned about cost,” Baenziger says.

According to Ibrahim, his team will continue to try new combinations every year and then will need to test the hybrids for several more years before anything is released.

“Within five years, I hope we can have the first commercially available hybrid seed available for producers,” Ibrahim says.

He adds that in addition to the fieldwork, his team now has access to medium- to high-throughput genotyping, which will help them map the restoration genes and understand hybrid vigor at the molecular level. They are also screening the germplasm for the floral characteristics and for combining ability.