While the demand for organic crops has risen sharply in recent years, it’s a struggle to keep pace.

Not only is the demand for organic crops up in recent years, it is way up. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Agriculture Statistics Service, the demand for all organic crops in the United States increased by 69 percent between 2008 and 2014.

In 2015, the Organic Trade Association (OTA) reported that the U.S. organic industry posted new records, with total organic product sales hitting $43.3 billion, an increase of 11 percent from the year before. Of this $43.3 billion, $39.7 billion were organic food sales. Simply said: nearly 5 percent of all food sold in the U.S. last year was organic.

“As the demand for organic products increases, so does the demand for organic seed in all sectors, including the corn, soybean and sorghum sectors to meet the demand for feed and food products,” says Michelle Klieger, director of international programs and policy for the American Seed Trade Association (ASTA). “Over a dozen seed companies have developed varieties for this market and are selling seed for this market. With the diversity of companies, producers can purchase varieties with different maturities and characteristics.”

However, it is important to point out that demand varies by crop.

“As with other identity-preserved seed sectors, such as waxy and white corn, seed companies are able to meet market demand when they are given the appropriate lead time to produce for the demand,” says Klieger. “As organic farmers and seed companies develop relationships, the companies scale up their production processes to meet the growers’ demands.”

Even though 2015 showed significant growth for the organic industry, meeting consumer demand remains a big challenge. OTA reported that in response to organic production lagging consumption, the industry has come together in creative and proactive ways.

“The industry joined in collaborative ways to invest in infrastructure and education, and companies invested in their own supply chains to ensure a dependable stream of organic products for the consumer,” says Laura Batcha, CEO and executive director of OTA.

Increased Investment

According to a report, “State of Organic Seed 2016,” released this past June by the Organic Seed Alliance (OSA), investments in organic plant breeding have increased and are resulting in more organic varieties and trained organic seed professionals.

More than 70 percent of these investments occurred during the past five years.

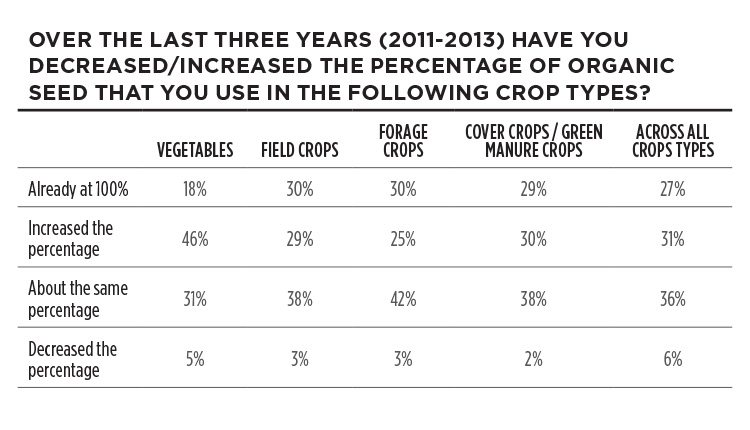

Kristina Hubbard, advocacy and communications director for OSA, says the alliance surveyed organic crop farmers and found that they are using more organic seed than they were three years ago.

“Organic farmers also report being happier with the quality of the organic seed they’re using,” she says. “And the vast majority of respondents believe organic seed is important to the integrity of organic food.”

Hubbard says organic seed is also a regulatory requirement. USDA’s National Organic Program (NOP) requires the use of organic seed when commercially available; however, the “State of Organic Seed 2016” report shows that supply gaps remain, as most organic farmers still rely on seed that isn’t organic.

But Hubbard says the situation is improving. “OSA arrived at this and other conclusions through a number of surveys targeting stakeholder groups, a detailed analysis of organic seed research investments, and listening sessions at organic farming conferences in 2014 and 2015,” she says.

Sam Jones-Ellard, public affairs specialist with USDA’s Agricultural Marketing Service, says while the Crop Progress Report does not break out organic production data from general production data, USDA’s National Statistics Service recently published estimates of organic corn, soybean and sorghum acreage, production and sales in 2015. The survey, among other statistics, shows that certified organic farms operated 4.4 million acres of certified land in 2015, representing an increase of 20 percent from 2014. Slightly more than half the land (55 percent) was used to produce organic crops; the rest of the land was pasture and rangeland.

Jones-Ellard also says: “U.S. organic corn production for grain or seed, not including corn produced for silage, increased 30 percent between 2011 and 2015; soybean production increased 10 percent; and sorghum production more than doubled.”

Industry Challenges

While these numbers sound good, Hubbard says the largest organic farms still use relatively little organic seed, and that OSA’s data suggests that organic certifiers’ enforcement of the organic seed requirement is weaker compared to five years ago.

“While organic seed research investments have increased, they still pale in comparison to funding directed toward seed developed for conventional systems,” she says.

The general public may be surprised to learn that fresh organically certified produce from our local grocery story or farmer’s markets may not have started out that way.

With the increased use of genomics and other more expensive breeding technologies (that have led to the patenting and consolidation of crop seed stocks by an increasingly small number of private seed companies) more organic farmers lack access to seed stocks uniquely tailored to their growing needs.

The OSA report says this is particularly problematic for organic farmers, who use 75 percent organic seed on average for operations under 10 acres, but only 20 percent organic seed on average for operations over 480 acres.

Hubbard says organic farmers report that genetically engineered (GE) crops harm the integrity of their products, since GE is an excluded method in the organic standards.

Another challenge, she says, is broader seed industry consolidation, which affects all farmers.

Hubbard points out that the conventional seed industry may soon witness two of the biggest mergers in history.

“Consolidation, and the restrictive intellectual property rights that incentivize this level of market restructuring, is an injustice to American farmers who experience less choice and pay higher prices for seed,” she says.

But the problem also offers an opportunity, she adds, “as the organic community can create a path for organic seed that provides an alternative to the dominant system.”

A number of smaller organic seed companies have emerged in response to consolidation, while others have also been motivated to take seed into their own hands.

“As an organic grower, I started growing my own seed because we were experiencing loss of seed choices as a result of consolidation in the seed industry,” says Dale Coke of Coke Farms in Aromas, Calif.

Coke has been farming for more than three decades and grows vegetables, grain, fruit and seed crops on 450 acres. “Now we also grow seed to ensure we have options that are organic, and to help address gaps in organic seed availability,” he says.

ASTA’s Klieger says as demand increases, seed companies face two major challenges.

“First, the lead time to produce seed is one to two years from when the order is placed until sufficient seed can be produced for delivery,” she explains. “Each season, seed companies produce enough new inventory to meet their estimated demand for the following season.

“That estimate is based on their sales in the current season and, like in any industry, seed producers do not want to produce seed they may not be able to sell. So it is imperative that organic producers work with seed companies well in advance of the time they will need seed for planting.”

Klieger says that this is especially true in a specialty market such as organic seed, where total units sold is less than 5 percent of the overall corn seed market. The second challenge is breeding varieties that can survive and be profitable even without inputs normally available to conventional farmers.

“With the limits on allowable organic inputs, the seeds themselves must be more resistant to diseases and better adapted for natural pressures,” she says.

What’s Next?

So, what is next for the organic food and seed industry to overcome these challenges?

USDA’s Jones-Ellard says the USDA and several major U.S. food companies have developed initiatives and strategic partnerships aimed at increasing overall domestic production of these crops, which could spur additional organic production and demand for organic seed.

“Seed companies will continue to work with their organic grower customers to meet the demand they have for seed to be used in their organic production,” Klieger adds. “As breeding techniques continue to evolve and provide opportunities to improve varieties, America’s seed companies will continue to strive to maximize the potential that is in the seed.”