Seed World LATAM wishes you a happy holiday season. As you celebrate this special time with your loved ones, we invite you to take a moment to relax and enjoy some inspirational reading. Explore our daily posts with the best content of the year, ideal for this warm holiday season.

Success in the seed industry doesn’t stop at innovation—it also demands understanding and navigating diverse cultures. This article explores how cultural intelligence plays a pivotal role in building strong relationships, negotiating across borders, and driving growth in the global seed sector. From bridging gaps in communication to fostering collaboration, discover the strategies that industry leaders use to thrive in an interconnected world. A must-read for anyone aiming to succeed in cross-border agricultural business!

The seed industry is globalized, but are we? Cross-cultural competence is vital.

Planting seeds in unfamiliar terrain is a vivid metaphor for the uncertainty of doing business across borders in unknown cultures: You won’t know the exact yields of your harvest — or the costs of your mistakes — until the seeds you’ve sown grow. Being successful at home, where one literally knows the “ground rules” (pun intended), does not necessarily guarantee that applying the same strategies will lead to success elsewhere.

Recently, Seed World LATAM had a chat with an American plant breeder who experienced the unexpected challenges of cultural misunderstanding. Early in his career, he’d traveled from the United States to Chile to oversee a winter nursery program.

The American was a highly educated Ph.D. scholar and CEO of a new company. His previous experience in agriculture had been in an academic environment, but in this situation, he was “the boss” for the first time. Assigned to work with him was a “campesino,” a farmer with an 8th grade education who was an experienced farm laborer on local lands.

The American instructed the farmer to sow the seeds at a planting depth of 1-1.5 inches, as he had successfully done in the U.S. countless times throughout his academic training. The campesino knew one inch was not enough; given the hot sun in Chile, he would normally plant those seeds at 2 to 2.5 inches.

If the campesino had spoken up, the American would likely have appreciated the advice. Culturally, North Americans usually value feedback positively rather than seeing comments from a subordinate as disrespectful interjections. They also naturally tend to assume that relevant information will be provided.

Coming from a Chilean background, however, the campesino had a different view of the power dynamic. For him, the American was in charge and probably knew more than him. Therefore, he would never dare to challenge his boss’ authority.

The campesino obediently did as he was told, and as expected, the intense Chilean sun burned the seeds. Not a single plant emerged, and the whole field needed to be reseeded.

Moving across the world was far more challenging than the American had foreseen, but worth a very valuable lesson: many of the biggest cultural differences can go entirely unnoticed… until they’ve caused a significant problem. That’s why cultural awareness is crucial when working across borders. While in the case of the plant breeder and the campesino, the gap in cultural understanding was based on perceptions of power relations between superiors and subordinates, also known as power distance, there are notable differences worth considering when doing business internationally.

Cultural intelligence, which is the capacity to adjust in unfamiliar and culturally diverse situations, is the key to working abroad successfully and avoiding some embarrassing faux pas.

Sometimes, we can laugh at these anecdotes, but sometimes, they come at a high price.

Understanding Cultural Perceptions is Key

Power distance, the extent to which less powerful members of a society accept vertical power relations, is one of the cultural dimensions that most differs between cultures.

In very general terms, South American countries are high-power-distance cultures. Subordinates tend to be much more comfortable with deference, respect, and obedience to their elders and superiors than they are with exercising proactivity or daring to express disagreement.

On the opposite side of the power spectrum, those from low-power distance cultures, like North Americans and Nordic Europeans, tend to have horizontal relationships. This means that they engage in interpersonal relations at the same level, and subordinates act independently without necessarily requiring instructions from above.

These generalities are quite relative rather than absolute. Of course, every country, organization, and individual is unique.

One of the most common mistakes is assessing other people’s behavior through our own cultural lens, says Coco Hofs, a Dutch-born intercultural trainer and founder of the intercultural consulting firm, CCS – Cross-Cultural Solutions. With over a decade of experience, she has helped countless organizations overcome cultural differences in the international workplace.

“When we think about other cultures, we do it from the lens of our own culture. So, for example, in an encounter between a Canadian and a Dutch person, Canadians are likely to be perceived as not so assertive. But that is not the case.

“That’s the behavior of the Canadians through a Dutch lens. I think that categorizing the behavior of another culture without looking at our own is one of the most common pitfalls because you start off on the wrong foot by creating somewhat of a stereotype, which is dangerously misleading,” she says.

Another common mistake is putting a whole continent into the same bag, culturally speaking. People mistakenly speak about a “Latin American culture” as if it were only one, which is equivalent to talking about the whole European culture as one.

“This is a dangerous assumption because there are huge differences in how neighboring countries, like Chile and Peru, do business. For example, whether it is okay to talk about business over lunch: in Chile, it’s acceptable and common practice, but in Peru, it’s frowned upon,” she says.

In the Global Seed Industry, Culture Affects Everything

Cultural dynamics affect everything we do: how we greet one another, how we sell our services and products in different markets, how we engage with people at different levels of hierarchy, our notions of time, our adherence to regulations, and so on. There is not one aspect of our lives that isn’t tinted by our culture.

Likewise, in the global seed industry, culture shapes all aspects of seed production, distribution, consumption and regulation. Understanding and accounting for cultural factors is essential for seed companies, policymakers and stakeholders to effectively navigate the industry’s complexities and address the diverse needs and preferences of different communities and regions.

Cultural attitudes and beliefs go beyond general dynamics like power structure. For example, cultural attitudes toward biotechnology and genetically modified organisms — and, more broadly, trust in science —shape both the regulatory landscape and consumer acceptance of new breeding techniques in different countries and regions. While some cultures, like Argentina, Brazil and Paraguay, are more culturally prone to embrace biotechnology as a means of enhancing agricultural productivity and sustainability, other countries, like Ecuador, Peru and Mexico, are more likely to harbor concerns about GMOs’ safety, ethics and environmental impact. For that reason, seed companies and policymakers must consider these cultural perspectives and invest more in transparent communication and dialogue with stakeholders in those countries that don’t already support biotech innovations.

Building trust is essential. But that, too, is done very differently across the globe. If we look at the Canadian way, it’s relatively task-driven. For example, a Canadian entering into a business relationship would have confidence that they will be paid because they have signed a contract, there’s an approved quotation, previous experience showed the partner is a good supplier, and so on. So, the source of their trust is cognitive, very much driven by the brain. In comparison, South American business deals are based less on paper and more on trust in relationships.

As Hofs explains, “In South America, trust is built much more through the relationship; it is an emotional trust, coming from the heart.”

Regardless of country, what remains constant is the need for an ongoing investment in building a relationship so that trust can develop, she adds.

“Once you are able to build trust in a relationship, anything that goes wrong after that lands softer. Like, if you accidentally give someone super harsh feedback and they take it really personally, if there’s previous trust, then that person will recover faster.”

A Global Seed Leader’s Insights

Dean Cavey, Managing Partner at Verdant Partners LLC, has over 40 years in the worldwide seed industry. He shared several tips from his experience advising numerous seed companies on mergers and acquisitions at a global level, primarily in the US, Netherlands, France, Eastern Europe, Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Australia and Japan.

“Even though we may speak different languages, we all sort of speak the same language as it relates to agriculture. People have common problems, common goals and common issues in the food and agriculture space.”

Despite the commonalities, he recognizes the importance of learning about his counterpart’s culture.

“Outside the U.S., particularly when we’re dealing with smaller, family-owned companies, it’s important that we understand the family dynamics and ask questions about who makes the decisions, and how they make the decisions, so we can try to avoid any embarrassing missteps.”

Cavey remembers a particular event in which he and his colleague were giving a presentation to the board of directors of a Japanese company. None of the Japanese said a single word during or after the presentation. This made the Americans think they had failed miserably.

After they had a chance to sit and speak with the CEO of the Japanese company and express their concern, the CEO responded that silence is an integral part of the Japanese speech style. If they had asked questions or made comments during the presentation, that would have been seen as disrespectful. They typically meet afterward and talk internally about a presentation or meeting; they reach a consensus and later communicate it.

The cultural dynamics Cavey is referring to are indirect (Japan) versus direct (U.S.) communication styles. Many Asian and Eastern European countries prioritize harmony, avoiding confrontation and seeking consensus through subtle cues and non-verbal communication. However, they may need to be mindful of assertively expressing their opinions and advocating for their interests in collaborations with partners from more assertive cultures.

North American and Germanic cultures tend to have clear, informative, get-to-the-point communications. They prefer being truthful rather than diplomatic and do not fear confrontation. However, they need to be aware that overly direct approaches can be perceived as insensitive or inflexible in cultures with different communication styles.

The Culture Map: a Framework for Working Internationally

Cross-cultural competence is not about knowing all the ins and outs of all the cultures that you interact with because that would be impossibly time-consuming and would entail constantly readjusting and reassessing. Training organizations on cultural perceptions — meaning how we come across to others and why — typically suggests using a cross-cultural model like the Culture Map model, created by Erin Meyer, a professor at INSEAD, a leading international business school.

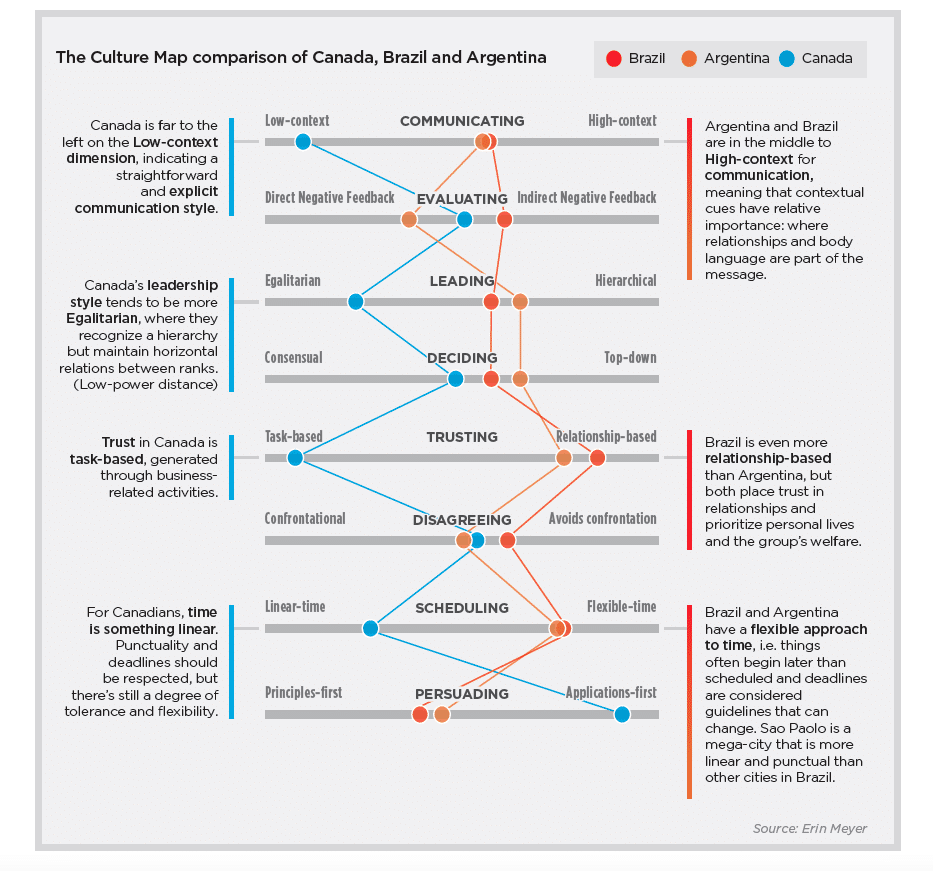

The sample model below shows where three countries — Brazil, Argentina, and Canada — tend to fall culturally in several key categories, including communication or decision-making. Understanding a business partner’s cultural tendencies is an excellent starting point for building better business relationships.

The model is a highly effective framework for visualizing and understanding how people behave differently depending on where they come from. Tools like the Culture Map can help international organizations adjust their operation strategies and define far more convenient and effective courses of action.

Like Erin Meyer’s Culture Map, there are numerous helpful tools and models, such as Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions Framework or Richard Lewis’ Cross-culture Model, which provide valuable insights for seed companies engaging in international collaborations within the global seed industry.

By understanding and respecting cultural differences in communication styles, time orientation and social dynamics, seed companies can build stronger relationships, enhance collaboration and mutually “suc-seed” in their cross-cultural partnerships.