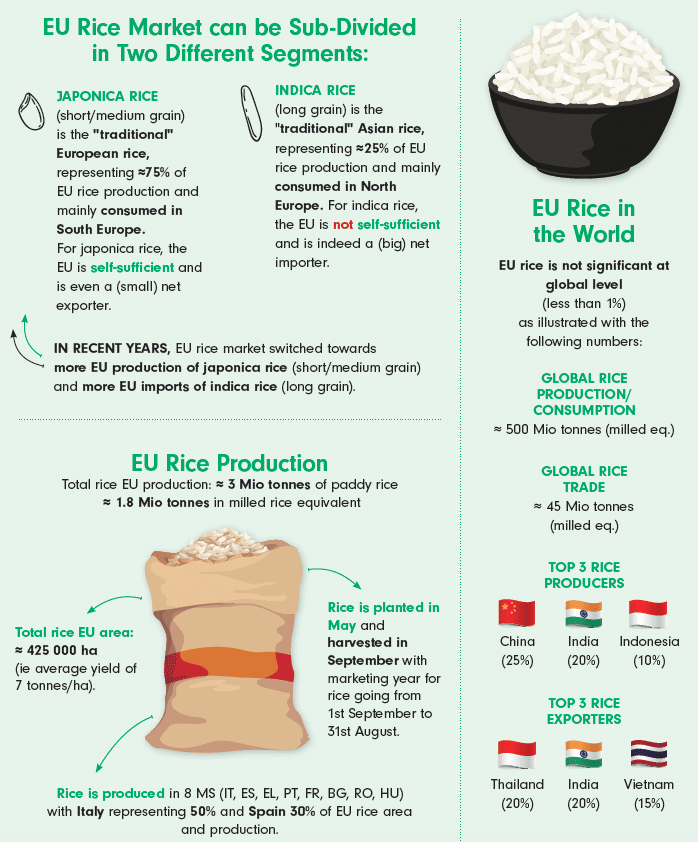

In Europe, rice is produced in eight EU Member States (IT, ES, EL, PT, FR, BG, RO, HU), with Italy representing 50% and Spain 30% of EU rice area and production. But the crop is suffering more and more from a nasty fungus: rice blast (Pyricularia oryzae). It evolves rapidly and has gained resistance to certain fungicides. The fungus infects the leaves of the rice plant, and when it is flowering, the blast can spread to the neck and infect and destroy the seeds. The pathogen can lead to a 50% reduction of rice production. So, the crop is in dire need of solutions, and help is coming not only from conventional plant breeding but also from gene editing.

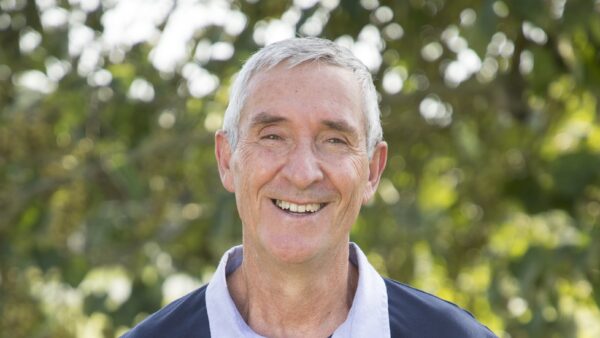

Seed World Europe sat down with Vittoria Brambilla, a plant scientist at the University of Milano, Italy. She and her colleagues worked together with a group of UK plant pathologists, developed gene-edited rice at the University of Milan and obtained permission to set up a trial in the open field to see how resistant the gene-edited plants would be to a fungal infection.

That first field trial with gene-edited plants was planted in May 2024 and met with great excitement by scientists, both Italian and international. Unfortunately, about five weeks after planting, vandals pulled out the rice plants and destroyed the trial. Luckily, Brambilla was able to save about 100 of the 400 plants. And recently the seeds on these remaining plants were harvested and are now in a safe place to be used in next year’s trial.

Seed World Europe (SWE): Vittoria, why have you chosen rice, and this fungus as your target for your gene-editing research?

Vittoria Brambilla (VB): Actually, we didn’t choose rice. This was the species on which we were performing our research in the laboratory. Therefore, we had already developed all the tools to manipulate this species in vitro and also by molecular tools. Our research interest in the lab was actually not the fungus that causes rice blast but flowering time. Nevertheless, we thought that to communicate these technologies to stakeholders, we needed to apply them to specific problems. We asked farmers which was the biggest problem for rice cultivation and most of them agreed on the fact that it was rice blast. We teamed up with plant pathologists and together we developed these gene-edited rice lines for improving the resistance to rice blast. We picked a rice variety that is very popular in Italy, as its grain makes excellent risotto.

SWE: How do rice farmers in Italy feel about your innovation?

VB: Farmers that are aware of these technologies in Italy are generally in favour of using them, they are looking for innovation and welcome the arrival of rice blast-resistant varieties.

When the rice blast was getting worse, we received more support for our project especially from farmers. We even got support from the country’s powerful trade unions. Along with scientists, they asked the politicians to allow field trials, since our approach used gene editing, and not GMOs.

SWE: The first field trial was destroyed in June. Can you share what happened?

VB: We planted this first field trial of gene-edited rice in Italy on the 13 May 2024, and as you mentioned, this field was destroyed shortly after, on 21 June. Of course, initially, we were really disappointed by this act of vandalism against our experiment. But then we got hundreds of messages of solidarity from people and companies. This was for us the confirmation that we were going in the right direction: Most of the people were appreciating what scientists were doing to improve agriculture and make it more sustainable. The plants were cut but not completely killed and could survive. So, the nice thing is we could propagate the seed during this season and now we have collected them and safely stored, and we will use them next year in a new field trial.

SWE: How has this vandalism impacted your research, and how did it impact the view on gene-editing in Italy?

VB: The vandalism delayed the collection of the research data, and we will need to wait until next year, but the good thing is that it brought attention to gene editing technologies in agriculture in Italy. This resulted in more support from the politicians and the public. We received a lot of solidarity from the Ministry of Agriculture in Italy.

SWE: Looking ahead, what could be a realistic time path towards commercialization of rice varieties with this fungal resistance in Europe?

VB: I cannot predict which will be the path for this type of plant to reach the market. This will largely depend on the political decision that Europe will take in the near future. Currently, Europe is possibly one of the places in the world with the most restrictive regulations against gene-edited plants as they are considered like GMOs.

SWE: What is your take on the regulatory environment for gene-edited research in Europe? Where can it be improved?

VB: As a scientist, I believe that for a product it is more important that a crop is good and safe for the consumer and the environment rather than if it was produced by conventional methods or biotechnological ones. At the moment a plant that is produced by random mutagenesis can go to the market in Europe like conventional plants. But plants that are produced by targeted mutagenesis or by gene editing, are considered GMOs. Also, gene-edited plants are often not distinguishable from plants that have mutations that have originated spontaneously and are also not traceable. For these reasons I think that a new regulation for gene edited plants needs to be written in Europe in the future, hopefully not too far in the future.