https://youtu.be/lTGjO-1mESA

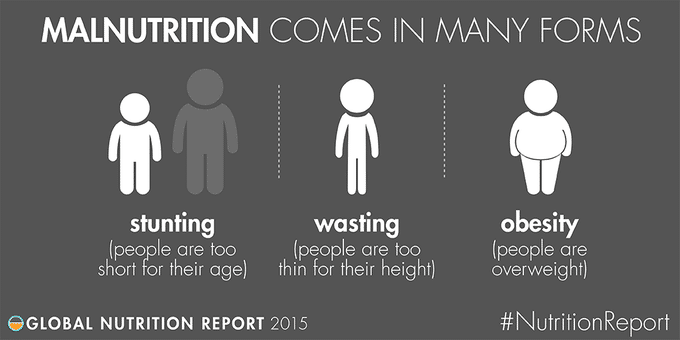

According to the World Health Organization, one in three people, around three billion in total worldwide, suffer from some element of malnutrition — either not enough to eat, nothing to eat at all, the wrong kinds of calories, or too much to eat.

Malnutrition includes more than just not having enough food, notes Geeta Sethi, advisor and global lead for food systems at the World Bank. With obesity rates at all-time highs in many developed nations, coming to terms with the fact that a third of all people aren’t properly nourished is only the beginning in building a global food system for a future in which climate change and other challenges loom large.

“Without a doubt, our current food system has provided caloric efficiencies for billions of people over many decades. That said, we’ve reached a point where current food systems are really creating a bankrupt planet and unhealthy people,” says Sethi, who will speak at the upcoming World Agri-Trade Innovation Summit.

“The fact is we cannot talk about agriculture alone when we talk about building modern, resilient food systems. We cannot meet the future without food systems being transformed. That requires a very different kind of a lens in terms of how we are now thinking about feeding nine billion people by 2050.”

Sethi is lead architect of the World Bank’s Food System Transformation agenda, a food system that focuses on what it calls a triple bottom line — prosperity, sustainability and healthy people. She also manages the World Bank’s program on Food Loss and Waste Reduction.

She has more than 20 years’ experience working as an economist on fragile, low-, and middle-income countries. What she’s seeing at the moment is a world where the hidden costs of the current global food system amount to $12 trillion, according to the 2019 Food and Land Use Coalition report, Growing Better: 10 Critical Transitions to Transform Food and Land Use. The World Bank is a partner in the coalition.

That’s not to mention supply chain difficulties caused by world events that we are woefully unprepared for. Bottom line, she says, is the current global food system is broken and has to be fixed.

Allocating Money Differently

But what needs to change in order to do that? A complete refinancing of food systems around the globe and the shift from large global food systems to many local ones designed to withstand challenges like climate change, poverty, and health crises like global pandemics.

“Close to $700 billion a year of public support is going into food systems, but it’s going to food systems in a way that’s creating these kinds of distortions in terms of people’s health and the planet’s health,” Sethi says.

The hidden costs of current global food and land use systems amount to $12 trillion compared to a market value of the global food system of $10 trillion, the Growing Better report notes.

“If a production system costs more than it the value of what it provides, that system is fundamentally broken and the way it is financed has to change,” she says.

That requires a repurposing of the $700 billion in public funding that goes into the global food system, which ultimately does not provide those one in three people with a proper diet.

“The international poverty line is $1.90. The cost of a healthy diet is close to $4 per capita. There is no way for three billion people to afford a healthy diet, yet those very people are paying billions into the food system that isn’t serving their needs,” Sethi says.

“Instead, could we not think about supporting them with very enhanced social protection programs that are actually coming out of public monies already allocated to agriculture?”

This, she says, would cause a domino effect.

“If more people can afford a healthy diet, food manufacturing itself will be transformed. When more people are demanding healthy food, that rewards the producers of healthy food, which in turns makes it more affordable for everyone, but especially lower-income households. At the same time, producers of unhealthy food are penalized.”

According to the Growing Better report, more people demanding healthy food would spur CEOs and company boards to recognize the risks of a business-as-usual strategy and commit their companies to science-based targets in line with initiatives like the Paris Agreement and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. The private sector would put in place easily monitored plans for reshaping their supply chains, product development, and marketing strategies in line with healthier diets and nature-based solutions, expanding choice and inclusion.

Additionally, they would work more closely working with government, academia and civil society, which are the best determiners of what functional global food systems of the future look like, the report adds.

Plant Science Plays a Crucial Role

As consumers demand more healthy, fresh food regardless of where they live, a problem inevitably arises: how can the shelf life of said healthy food be improved to meet the demand?

“Anything that increases the shelf life of food without impacting nutrient content will be welcome. Perishables are prone to higher losses and waste. A major challenge for the developing world is that due to inadequate agro-logistics, fresh food can’t reach shelves. That’s where technology is needed to improve the shelf life of healthy food so that food has a chance to actually get to consumers,” Sethi says.

Breeding for climate change is also critical. She notes that crops which are in demand by consumers must be nutritious while also being resilient to drought and flood.

“Plant breeding will be a crucial part of a suite of technologies that will help us meet the demands of climate change and a rising global population. Plant varieties adapted to local conditions will be a necessity as the current global food system is replaced by a network of local supply chains that put a focus on human health, sustainability and economic prosperity.”

For more info on the World Agri-Tech Innovation Summit visit worldagritechusa.com.