This year marks 145 years since mankind discovered the benefits of hybrid plant varieties. In many crop species, hybrid varieties have become commonplace, but why is it that we strive for hybrid varieties? And why are certain fringe groups in society still questioning their usefulness?

The major reason why hybrids plant varieties are so popular is because of a phenomenon called ‘heterosis’. Plant breeders and scientists noticed, that when they began crossing different lines that were homozygous, non-segregating (so called ‘pure’) lines, that the resulting hybrid plants (so called ‘F1 hybrids’) were usually more vigourous than their parents. They had discovered “hybrid vigour“, also called ‘heterosis’.

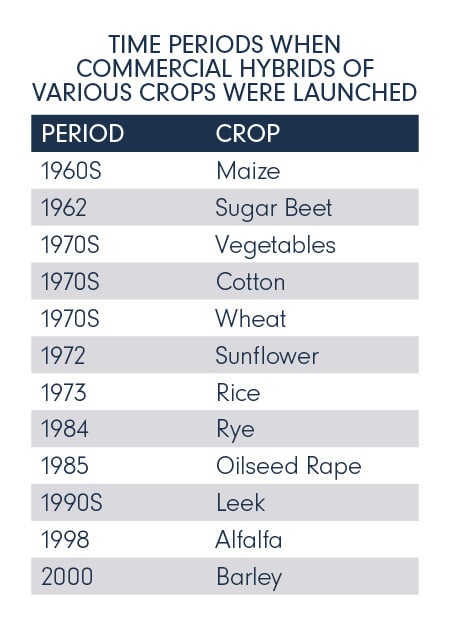

Over the years, hybrids varieties have become more and more commonplace in a wide variety of crops, and we have all grown up with plant hybrids being all around us. The table shows the time periods in which hybrid varieties of various crops were released.

We are enjoying the products of hybrid varieties on a daily basis, with bigger harvests from the fields, and high-quality vegetables on the grocery shelves. But perhaps it’s good we briefly take a few steps back and see where it all began. The realization that the crossing of carefully selected parent lines can create a hybrid plant variety that (well) outperforms the best parent line was done by several people, more or less simultaneously.

It was Charles Darwin himself who, in 1876, wrote down his theory of ‘hybrid vigour’. A year later, William James Beal, became the first to cross-fertilize corn for the purpose of increasing yields through hybrid vigour. In 1881, Eugene Davenport and Perry Holden published an account of a field experiment demonstrating hybrid vigour in corn.

In 1906, Herman Nilsson-Ehle pointed out that part of the offspring of experimentally produced hybrids combined the valuable properties of the parents. Standing on the shoulders of giants, George H. Shull, developed his first maize hybrids around 1910, but commercial production of them did not begin until 1922. He also described heterosis in maize in 1908 but didn’t coin the term ‘heterosis’ until 1914. And finally, Edward East, around the same time as Shull, observed that when the self-pollinated plants were cross-pollinated to produce hybrid progeny, these plants sometimes were even more vigorous than the plants from which the inbreds had been developed.

As described above, for farmers and growers, the higher performance of hybrids is one of the benefits. Yield increases of 20 to 50 per cent have been recorded. Another clear advantage is that the plants are fully homogeneous and predictable. The plants mature at the same time, making harvest and post-harvest processes easier.

One of the few drawbacks to hybrid varieties is that a large amount of time and money goes into the creation of the right parent lines and finding the right parent line combination that leads to the best performing hybrid in a certain environment. This leads to a slightly higher seed price, which in basically all cases is earned back by the higher yield and better performance of the hybrid. Self-pollinating the F1 hybrid plants leads to a heterogeneous and segregating population, which is not expressing the hybrid vigour. This makes it less attractive for a farmer to save seeds. Another drawback could be that all plants mature at the same time, which leads to a peak in harvest labour and produce. For some a benefit, for others a drawback.

There are many examples of the benefits: nearly all field corn exhibits heterosis and corn yields in the U.S. increased sixfold. Hybrid rye varieties give 10-20 per cent higher yields, improved lodging resistance and improved sprouting resistance compared to open-pollinated varieties. In Mali, hybrid sorghum varieties can produce a yield of three to four tonnes per hectare, compared to non-hybrid varieties that manage two to three tonnes even in a good season. Hybrid rice varieties have showed a convincing yield superiority over previous high-yielding non-hybrid varieties. Finger millet is one of Kenya’s most important drought-tolerant cereals, but farmers have not expanded production much because of low yield. The recent release of a new hybrid variety (yielding 18 and 24 — 90 kg — bags per hectare, compared to the maximum 12 bags per hectare from existing varieties) provided a welcome boost for the farmers.

In short, over the past century, hybrid plant varieties have provided massive benefits, and helped stave off hunger, ever since they were introduced.