This article provides a summary of my talk at the 2019 EuroSeeds Annual Congress, titled “Diversifying Directions of Knowledge and Value Flows: A Blockchain Use case in the Agro-Seeds Sector.” It describes how blockchain can potentially be used in the seed sector to incentivize the sustainable and equitable sale and use of agrobiodiversity and heterogenous material in agriculture on one hand, while also incentivizing benefit sharing and equitable downstream research with this biodiversity.

It was a pleasure, and a surprise, for me to address a hall full of experts from the industry, government and non-governmental organizations at the EuroSeeds Congress in October last year. A pleasure, because it is rare for me as an ethics, law and intellectual property academic specializing in sustainable agriculture, to meet so many experts who have deep knowledge and genuine interest in agriculture. A surprise, because as an academic and entrepreneur also looking at how blockchain and Artificial Intelligence (AI) can help resolve issues that laws have failed to adequately address, it is rare to find agricultural experts eager to learn about these technologies, their promises and limitations.

The talk highlighted how blockchain technology (in combination with other technologies like AI and Machine Learning) may support sustainable and equitable agriculture which (economically) benefits both small farmers and corporations, and help overcome issues that intellectual property law and biodiversity conservation regulations have together not been able to optimally resolve.

THE EU ORGANIC REGULATION

‘Seed Keeping’, an art and practice still common in developing countries like India (see Box 1), is relatively less known, and in several instances, forgotten, in Europe. It involves careful selection and natural storage (or ‘keeping’) of the best seeds from a harvest resulting from sowing traditional or indigenous (namely, non-uniform or heterogenous) seeds. These stored seeds are then used for the next season’s sowing and the cycle continues. For several decades now, EU member states, in keeping with EU Directives, have either outlawed or actively discouraged the sale in agriculture, including for organic agriculture, of such non-uniform, heterogenous seeds. Recently, however, the European Parliament adopted the new regulation EU 2018/848 on ‘Organic Production and Labelling of Organic Products’. This regulation, declares in its recitals that “Research in the Union on plant reproductive material that does not fulfil the variety definition as regards uniformity shows that there could be benefits of using such diverse material, in particular with regard to organic production, for example to reduce the spread of diseases, to improve resilience and to increase biodiversity.” (Recital 36).

The Regulation also clarifies that such plant reproductive materials, which do not “belong to a variety, but rather belong to a plant grouping within a single botanical taxon with a high level of genetic and phenotypic diversity between individual reproductive units, should be available for use in organic production.” (Recital 37). Accordingly, for the first time, the regulation permits and actively encourages not just the use, but also the sale, for organic agriculture, of non-uniform seeds and planting materials that do not fulfill the definition of ‘variety’ (termed in the regulation as ‘plant reproductive material of organic heterogenous material’. Hereinafter, we refer to these materials as ‘heterogenous materials’).

The Regulation permits such sales to take place without the need to fulfill the arduous certification requirements under various EU laws (EU 2018/848, Article 13). However, in “order to ensure quality, traceability and compliance” with its requirements, the Regulation delegates “setting out certain rules for the production and marketing of… heterogenous material of particular genera and species” to the European Commission (EU 848/2018, Recital 38). These Rules are yet to be finalized, but the provision is expected to come into force in 2021.

INCENTIVIZING THE DISSEMINATION OF AGROBIODIVERSITY

Thus, although seeds like Sona Moti are highly relevant for breeders, legitimate access to these seeds with equitable benefit sharing with local farmers is unlikely to take place. While the new EU Organic Regulation and several existing international treaties (e.g. the Convention on Biological Diversity – CBD, and the Seed Treaty) attempt to reverse such trends by adopting legislations permitting the easy marketing and registration of locally adapted, heterogenous materials like Sona Moti, more fundamental issues remain unaddressed (and perhaps un-addressable by mere legislation). These issues include lack of trust (fear of biopiracy), preventing farmers from sharing agrobio resources, and absence of means facilitating their traceability to source after any instance of sharing or sale.

These issues together prevent wider dissemination of agrobiodiversity and agricultural best practices associated with their cultivation and maintenance in situ [1, 2], leaving farmers who generate and improve agrobiodiversity, economically weak and socially marginalized [3]. Adding to the problems are regulations aimed at preventing biopiracy that create multiple bureaucratic hurdles, either disincentivizing research with agrobiodiversity, or disincentivizing honest access and use practices. Lack of research incentives (and systems facilitating honest disclosure), further weaken consumer and farmer incentives to consume the harvest of/cultivate with local and heterogeneous materials, not least because their advantages over conventional and mainstream varieties of seeds and food remain unknown or unconfirmed by reliable scientific research [4, 5]. A vicious cycle is created when, as a result of ever reducing economic benefits accruing to farmers generators and improvers of agrobiodiversity, researchers themselves notice a reducing number and diversity of viable, actively cultivated agrobio resources being available for research [6, 7]. In addition to the lack of relationships of trust and easily implementable benefit sharing and traceability mechanisms, therefore, sub-optimal incentives to cultivate and research with agrobiodiversity are centrally responsible for its continuing and rapid loss.

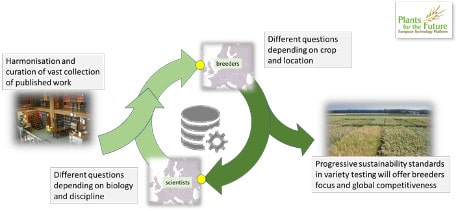

BENEFITS OF DATA PLATFORMS

Data platforms based on public or consortium blockchains with appropriate software architectures and consortium governance models can help solve problems of trust, traceability, incentives and equitable data collection. They empower data providers to collectively track, control and monetize the usage of their contributed data and assets. In particular, such systems can help by

- maintaining an immutable record of transactions/transfers of agrobiodiversity from farmers to various categories of end users;

- collecting data about the agrobiodiversity transferred, such as unique cultivation methods, special characteristics etc.;

- securing/protecting the data through the deployment of technologies such as hashing and encryption, thereby also helping to ensure that the contributors and transformers of data can retain control over who can use the data, how and when it can be viewed or accessed;

- structuring the data to be used in associated solutions (such as AI and ML solutions) in a manageable form, and

- facilitating automatic transfer of monetary benefits for the contributors of data, especially from their use in diverse applications, thereby effectively incentivizing continuous cultivation and engagement with agrobiodiversity.

CONCLUDING WORDS

Data, including data associated with agrobiodiversity and locally relevant heterogenous materials, is increasingly considered a tradeable commodity. However, the transfer/sharing of such data needs to be regulated to facilitate its safe, beneficial, sustainable and equitable use in downstream research as well as in various emerging technological applications, the most prominent of which are AI/machine learning applications. With growing economic & political relevance of data, several major ethical issues linked to its use are also surfacing. Platforms that adequately address these issues are indispensable to the meaningful & widespread adoption of (AI) applications that rely on data to design solutions for any specific sector/use case. Digital Ledger Technologies (DLT), including blockchain, can potentially help address several of these ethical issues, including issues of

- trust and privacy;

- secure and “controllable” data sharing;

- fair, inclusive and equitable economic benefits for those sharing data, and

- traceability (for purposes ranging from economic benefit sharing to liability determination).

Further, with the adoption of blockchain/DLTs and associated AI/Machine learning platforms, the direction of data/knowledge flows in the agricultural sector can and should be diversified (Kochupillai, 2019; Kochupillai et al., 2019)[8, 9]. In particular, while currently data/knowledge flows primarily (or almost exclusively) from the formal sector (academic, industry) to the informal (farmers) sector, making the latter net consumers of knowledge, blockchain and AI applications can help diversify this trend. In particular, blockchain/DLT can help farmers engaged in traditional and sustainable agricultural practices using local heterogenous seeds, and traditional soil and ecosystem management methods, manage and monetize their data/know-how while sharing these with AI/Machine learning apps and other users and stakeholders. This would significantly help incentivize and accomplish a goal that is of current and growing global relevance, namely, incentivizing research and on farm innovation with agrobiodiversity.

‘Seed Keeping’ & ‘Sona Moti’ Wheat

Dr. Prabhakar Rao of the Sri Sri Institute for Agricultural Sciences and Technology Trust, India (SSIAST, 2020) not only holds a Ph.D. in plant breeding, but is also a world-renowned architect and blockchain enthusiast. His most prominent passion, however, is ‘Seed keeping’, about which he has spoken extensively in TEDx Talks (TEDx 1 and TEDx 2) TV (CNN, 2019) and newspaper interviews. Rao and the various Indian NGOs the SSIAST works in collaboration with, is actively involved with reeducating farmers, especially small and marginal farmers, in the art and science of traditional agriculture that involves the ‘keeping’ and usage of traditional, indigenous, non-uniform seeds, especially for organic or ‘Natural Farming’ (Köninger et. al 2019). So far, more than 2.5 million farmers have been trained (AoLF 2019) in this art and science in India by SSIAST alone. More fascinating is Rao’s experience with farmers who are actively practicing ‘Natural Farming’ with indigenous, non-uniform seeds: they actively contribute to the revival and spread of local and often long-lost indigenous seeds and planting materials. Most recently, Rao and SSIAST’s partner NGO, the Art of Living Foundation (AOLF), rediscovered a five thousand year old indigenous Emmer wheat seed (Leeds, 2019) while on tour in the Indian State of Punjab. The seed was christened ‘Sona Moti’ (Golden pearl) soon after its discovery by the founder of AOLF, Sri Sri Ravi Shankar, amidst significant fanfare in a large festival organized for small farmers in early 2019. Sona Moti was also declared, based on local laboratory tests, to be the only wheat in the world that contains folic acid. Within days of its (re)discovery, direct marketing channels were established between cultivators of Sona Moti and city wheat consumers, such that the farmers’ Sona Moti stocks were sold out even before the actual harvest – at several times the retail price of the popular high yielding wheat varieties.

Euro Seed Congress Live Survey

Several seed companies recognize the importance of agrobiodiversity for plant breeding. However, only a few source their breeding materials from in situ farmer-sources (e.g. from farmer-custodians of old potato varieties in the Andes – See European Seed 2018). Most rely on gene banks or their own private collections. This trend was also clear from the live survey conducted during the 2019 EuroSeeds Annual Meeting in Stockholm (October 2019), where 53 responses were received from seed industry representatives to the question „Reasons and Level of interest in agrobiodiversity conserved in situ.” 50% of the respondents declared the interest level to be high, with the reason that such biodiversity is necessary for R&D. Yet, only 3% of the respondents identified Farmers as a primary source of germplasm for the creation of new varieties. The remaining 50% cited the interest level to be medium to low either because access was difficult due to legal and regulatory hurdles (e.g. regulations mandating benefic sharing) or because knowledge was unavailable as to where to access materials, or because the benefits of these materials were unknown.

* Dr. Mrinalini Kochupillai is a senior academic researcher and Founder-Director of Sustainable Innovations Research and Education (SIRN). She is currently in the process of establishing a blockchain-based start-up in the agri-seed sector.

References that are not included in the below list are hyperlinked for access. I would like to thank Ulrich Gallersdörfer for his suggestions/comments on an earlier draft of this article, and Ms. Julia Köninger for her research assistance.

References

1. Aoki, K., Neocolonialism, anticommons property, and biopiracy in the (not-so-brave) new world order of international intellectual property protection, in Globalization and Intellectual Property. 2017, Routledge. p. 195-242.

2. Raustiala, K. and D.G. Victor, The regime complex for plant genetic resources. International organization, 2004. 58(2): p. 277-309.

3. Sebby, K., The Green Revolution of the 1960’s and Its Impact on Small Farmers in India. 2010.

4. Almekinders, C.J., et al., Understanding the relations between farmers’ seed demand and research methods: The challenge to do better. Outlook on Agriculture, 2019. 48(1): p. 16-21.

5. Louwaars, N.P., W.S. De Boef, and J. Edeme, Integrated seed sector development in Africa: a basis for seed policy and law. Journal of Crop Improvement, 2013. 27(2): p. 186-214.

6. Zhang, H., et al., Back into the wild—Apply untapped genetic diversity of wild relatives for crop improvement. Evolutionary applications, 2017. 10(1): p. 5-24.

7. Dempewolf, H., et al., Past and future use of wild relatives in crop breeding. Crop Science, 2017. 57(3): p. 1070-1082.

8. Kochupillai, M., Diversifying Directions of Knowledge Flows using Blockchain & AI to Equitably Monetize & (Re)distribute Value from Traditional & Sustainable Farming Systems, 2019, doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.17276.28805

9. Kochupillai, M., Köninger, J., Kopytko, N., Matthiessen, J., Radick, G, Rao, P., Incentivizing and Promoting Sustainable Seed Innovations in India: A Three Pronged Approach. 2019, doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.12670.74568/1