Last year, when the European Court of Justice passed a ruling relegating most new plant breeding techniques (NPBTs) to the 2001 GMO Directive (Directive 2001/18/EC), most hardened Brussels actors threw their hands up in the air and shouted: “No, not again!”. Accustomed to the European Union being the dead-end for innovative technologies, most of us responded with scorn, accusations and packed suitcases. But not everyone gave up.

A group of master’s students in various agricultural programmes in Wageningen University in the Netherlands took another, more pedagogical approach. They simply asked: How can we change the 2001 Directive to make it more relevant to the changing technology?

Sometimes it takes a fresh look with optimistic eyes (terribly lacking in the battle-scarred Brussels lobbying arena) to assume the European Commission does not want bad policy inhibiting good research. Maybe with the proper incentive, the bad GMO Directive could be made fit for purpose (or at least less bad).

The students proposed to update the 2001 Directive by providing clarity on the different seed breeding techniques via an amendment tailoring regulatory requirements per technique. On the first anniversary of the ECJ decision, the students launched the “Grow Scientific Progress: Crops Matter” Citizens’ Initiative.

They state: “Scientific and technical innovation have developed to an extent that requires a revision of the present Directive, with special regard to new plant breeding techniques (NPBTs).”

Their motivation was simple. The European court decision did not respect the science available that would make agriculture more sustainable, climate-friendly, reduce pesticides and food waste while also helping improve farming and food security in developing countries. These students did not want to do what the previous generation of European researchers was forced to do: pack a suitcase and export their skills.

The Dutch education system focuses on “problem-based learning”. These students saw the problems inherent in the European policy system (there was no workable definition of NPBTs) and found a solution. At the same time these students are giving the rest of us a masterclass in how to manage poor EU policy.

An exemption mechanism

The beauty was in the simplicity of their ECI proposal. The group knew they could not change the existing GMO Directive, but they could add a functional amendment which would provide an “exemption mechanism”. The first key element was to recognise in the Directive that the techniques of mutagenesis based NPBTs are not the same as conventional GMOs and the products are different.

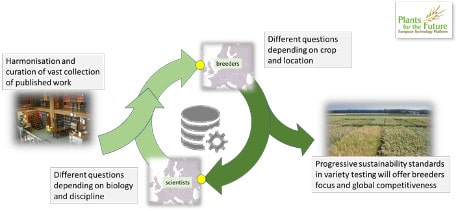

The amendment would create a “positive list of safe species-specific traits”. Products on this list would have no foreign genetic material or novel traits and would not require the arduous process of authorisation.

The goal here is to move the approval process on NPBTs towards a product-based risk-assessment rather than the focus on the process. If the traits could be achieved via traditional breeding methods, then they would be placed on the positive list and require only a notification procedure.

The students are dumbfounded by what happened last year with the ECJ decision. Creating obstacles for these new breeding technologies will only lead to less sustainable agriculture. At the same time, the innovative products will still be imported into Europe and more researchers will be forced to take their research skills outside of the European Union. Their Citizens’ Initiative is an appeal to common sense; it is an appeal to responsible innovation and scientific progress.

Support our future leaders

The initiative started in July with ten students. Given the sensitivity of the subject, they rightly chose to not accept help from large organisations or corporations. In October the team grew to 17 students. Getting a million signatures divided across all EU countries (including the UK) will not be easy and they need the support not only from the seed breeding research community, but all people concerned with innovation and agriculture.

In interviewing three of these students during the summer, I was impressed by their insights and understanding, inspired by their optimism and energy and reassured that Europe does have a future in plant breeding research. But they are taking on this ECI challenge by themselves and unlike the activists with large pan-European networks and deep pockets, they can only do so much with energy and a good idea. Please go to https://www.growscientificprogress.org/, sign the ECI and share this initiative within your networks and among your colleagues.

The future of European plant research and agriculture depends on the success of these young courageous scientists.