What it takes for a seed company to keep track of their genetic resources

In the eighties, countries started recognizing that biological diversity is a global asset of value to present and future generations. In response, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) started work that after a few years of negotiations would lead to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), which came into force in December 1993. The negotiating experts were to take into account “the need to share costs and benefits between developed and developing countries” as well as “ways and means to support innovation by local people”.

Around the same time, countries also recognized they were very much depending on each other for plant genetic resources for food and agriculture. To that end, a voluntary agreement, the International Undertaking on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (IU), was adopted in 1983. However, the IU was reliant on the principle of genetic resources being the common heritage of humanity. The CBD brought genetic resources under the jurisdiction and sovereignty of national governments. However, the CBD recognized the special and distinctive nature of agricultural genetic resources. Such resources are international, with frequent border crossings; their conservation and sustainable use required distinctive solutions and they were important internationally for food security. Subsequently, the IU was renegotiated to align with the CBD, and was renamed as a treaty: the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (ITPGRFA). To deal with the aspect of dependency, the ITPGRFA developed a system to facilitate access and benefit sharing for plant genetic resources for food and agriculture, through the so-called multilateral system. In that system, access and benefit sharing are organized through a standard contract that was internationally negotiated.

The main caveat however, was the access and benefit sharing through CBD was rarely happening and countries decided to develop a separate protocol to elaborate the whole access and benefit sharing process. After several years of negotiation, the Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit Sharing (ABS) was adopted in 2010 and entered into force on 12 October 2014, as a supplementary protocol to the CBD. Its aim is the implementation of one of the three objectives of the CBD: the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising out of the utilization of genetic resources, thereby contributing to the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity. However, there are concerns the added bureaucracy and legislation will, overall, be damaging to the monitoring and collection of biodiversity, to conservation, to the international response to infectious diseases, and to research.

In previous European Seed articles from 2014, we wrote about the Nagoya Protocol and its impact on the European seed industry. Now that we are three years down the road, it is time to take stock and see what kind of changes are needed in a seed company to comply with the emerging access and benefit sharing regulations. To find out more from a seed industry standpoint, European Seed sat down with Tonny van den Boom, Global Genetic Resource Coordinator Vegetables for Bayer; Xavier Bouard, Regulatory Affairs Officer at Limagrain; Mariann Börner, Gene Bank Manager for Enza Zaden, and Lisanne Boon, company lawyer at Rijk Zwaan, who spoke about the struggles that a seed company goes through, and if there is any benefit at all to these regulations. Anke van den Hurk, Deputy Director of Plantum, provided additional input.

European Seed (ES): How have the various Access and Benefit Sharing (ABS) regulations (IT & Nagoya) affected your company?

Tonny van den Boom (TvdB): We used to have an open global network of breeding programs with an active exchange of breeding material between the programs. Some of these programs have now been isolated by domestic ABS regulations, because governments claim sovereign rights over material in our collections which considerably hampers a free exchange of these genetic resources between different countries. In some cases, domestic ABS regulations even paralyze the exchange of genetic resources that originated from non-domestic material.

Mariann Börner (MB): The current ABS regulations hamper the free flow of genetic resources as source for innovation and breeding/research activities. For the constant need to develop varieties that are better adapted to environmental changes and customer wishes, the free flow of genetic resources is key. Companies face big administrative burdens and unrealistic requests to point out ownership to genetic resources that have been distributed all over the world since decades.

Xavier Bouard (XB): We keep watching at the developments of those regulations for years to anticipate as much as possible their practical consequences, to be and remain in line. Internal procedures of access and management of genetic resources (GR) are constantly being adapted to the new conditions resulting from the ABS legislations. Legal certainty and traceability are the main issues. Notwithstanding the Clearing House information web site, the accessibility to clear information concerning ABS national regulations is not easy and creates legal uncertainty. It can be in a language that we don’t understand, or difficult to understand due to local legal specificities or to their complexity, or unpublished. Without clarity, access cannot be possible. And, the never-ending ABS obligations makes burdensome the tracking and tracing of the accessed materials forever.

TvdB: We have to deal with legal uncertainty because many of the national ABS regulations are difficult to find and often difficult to interpret. Moreover, it is quite difficult to establish communication with the different National Focal Points because of a lack of response, language barriers and a lack of understanding of the way of working within the plant-breeding sector at the side of the National Focal Point. So, in order to ensure compliance with the ABS Regulations, we have had to implement a rigid system for access to genetic resources and administration of such access, and we have had to teach all of our breeders and scientist how to comply with it.

ES: What changes did you have to make to be in compliance?

TvdB: We have implemented procedures concerning the access to, and use of, genetic resources. We have modified certain business software applications used in R&D to be able to ensure compliance with the various ABS regulations. In addition we have appointed a specialized team to exercise due diligence (two full time employees), and last but not least, we have also established a company network of legal experts on ABS regulations.

MB: To ensure that our company is in compliance with all these regulations, we had to:

- get legal advice

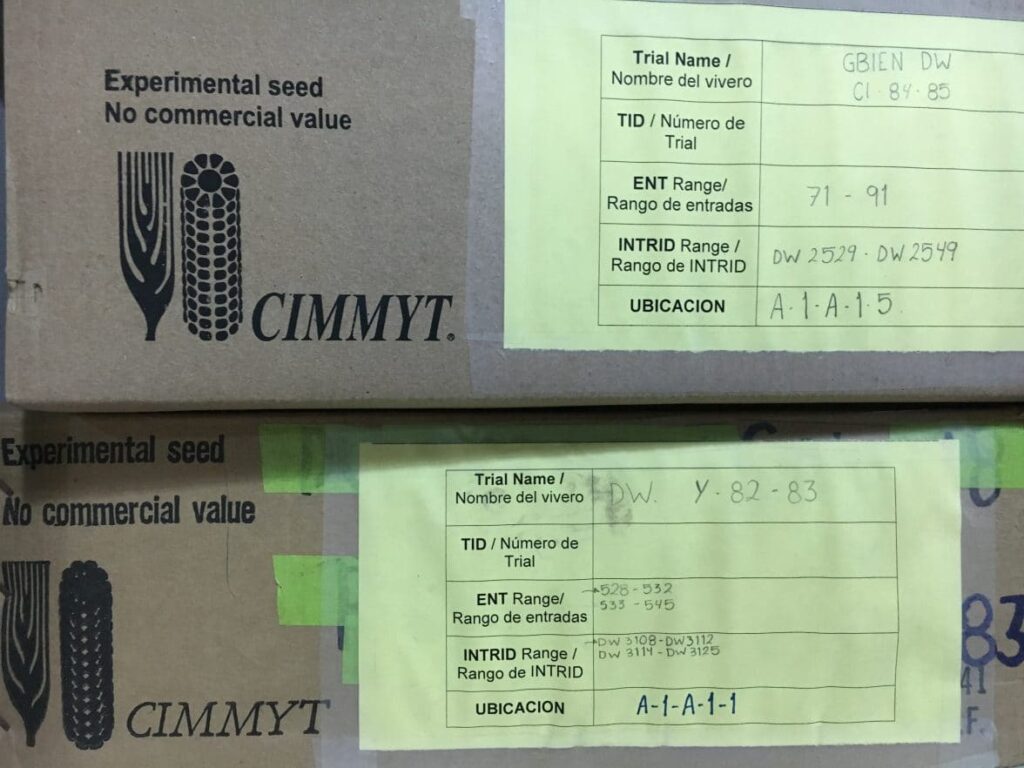

- build an advanced track and tracing system;

- set up a new internal procedure;

- create new responsibilities.

XB: Some of the practical consequences of these regulations are:

- adaptation of track and tracing tools;

- staff training to new legal constraints;

- development of internal procedures to secure access and use regarding ABS.

ES: I understand there is still a lot of unclarity on the regulations. How can this be solved, in other words, what do you need to arrive at legal certainty?

Lisanne Boon (LB): The website of the ABS Clearing House is an important source for information. But unfortunately, also on this website, the information remains very general. Some countries did already include the applicable legislation in their country on the website. But this is often a large document, most of the times only in the national language, which makes it difficult to find a quick answer to the question if Prior Informed Consent (PIC) and Mutually Agreed Terms (MAT) are required. To help the users comply with all these rules, it would be very helpful if the country profile on the ABS Clearing House website would contain some concrete information in English. For example, whether PIC is required. And if so, how it can be acquired.

XB: One of the issues comes from the endless obligations obliging to track and trace PGRFA forever. The seed sector needs to access GR under workable and bearable conditions. The multiple legislations must be clear and the practical pathway to access and use GR in each NP member must be clear and rapid. This means that:

- Legislations must be all published on the ABS Clearing House web site;

- They must be translated in English;

- As they can remain unclear, a summary of the steps and obligations to follow should also be published;

- The national authorities in charge of ABS should always give answers within reasonable delays;

- The ABS status of commercial varieties used as GR should respect the breeder’s exemption philosophy and therefore be freely usable for further breeding.

LB: Commercial varieties are very important sources for breeders. To develop new varieties that meet the demands of growers and consumers, it is important that breeders can continue to access commercial varieties freely, without unnecessary burdens. And, as they say, ‘No access, no benefits’.

TvdB: The National Focal Points of the countries which are a party to the CBD, should be obliged to publish their ABS regulations and ensuing measures on the ABS Clearing House website, and all regulations and measures should be summarized in a uniform way, where especially the scope of the measure should be transparent. Currently, it is too much of a burden on the users of genetic resources to contact the National Focal Points to find out the scope and jurisdiction of the applicable ABS regulations and measures. What we urgently need is more clarity; for example, by finalizing the draft sectorial guidance documents of the EU Commission.

ES: What would you advise to other seed companies?

MB: My advice would be that seed companies need to get prepared for more administrative tasks, and they would need to reserve capacity for that. In addition, I think they should be prepared for a slowdown of PGR exchanges.

TvdB: I would like to advise other companies to ensure that they have their procedures in order.

XB: We cannot pretend giving advice to other companies. Each company has to decide about its most effective approach of the ABS legislation, depending of its internal specificities.

Anke van den Hurk (AvdH): As dossier holder in Plantum, the association for seeds and young plants, we assist members in obtaining the right information on ABS obligations. We developed the first draft of recommendations for the members. These are taken over by the European Seed Association for further fine-tuning and will be finalized once the official guidance documents of the EU are finalized. Furthermore we keep the members informed on the developments through our newsletter and information meetings. In addition, we have once a month a telephone consultation hour.

ES: Overall, do you think there is a benefit to all these regulations? Or is it just a burden?

TvdB: Ensuring compliance with the Access and Benefit Sharing obligations ensuing from the Convention on Biological Diversity has proven to be quite a burden to the users of genetic resources. We believe that it will lead to a point where the users of genetic resources will avoid the use of genetic resources which are subject to ABS measures which in turn causes a lower availability of genetic variation. In order to assure conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity, we are of the opinion that the countries that are party to the CBD should not link the benefit sharing obligations to the use of individual genetic resources, because this creates a burdensome and inefficient system. Instead, we envision a system whereby users of genetic resources will contribute benefit sharing in a predictable and uniform way, without the need for negotiations and tracking and tracing of the use of individual genetic resources. This could be organized for example through a fixed fee and no administration.

LB: There is so much focus on all kinds of administrative formalities that people seem to be losing sight of what it is actually all about. The main aim is conserving biodiversity and the sustainable use thereof. I wonder how this can be accomplished, when breeders are reluctant to access new genetic resources because of the high administrative burden or uncertainty about the applicable rules.

MB: As long as Europe focusses on the benefit-sharing obligations with its regulations only and the potential countries of origin are not regulating their access obligations, it will be an unbalanced situation. A situation in which the goal to conserve and sustainably use biodiversity will not be reached and with that no long term benefit for the society will arise.

XB: In my view, we have now to bear with the ABS applicable regulations. The only remark we can make for the national implementations of the NP, can best be captured up by a French popular expression: the legislator “a mis la charrue avant les boeufs”. [‘putting the cart before the horse’; RED]. It means that the implementation of the ABS obligations at national level would, in most cases, need more time to enter into force in a practical workable form.

ES: How do you see the future, let’s say in 20 years from now? What will have changed because of these regulations?

TvdB: We expect that the countries which are a party to the CBD will be disappointed by the amount of benefit sharing actually collected from the users of genetic resources and we expect that therefore the respective countries will be working on the successive legislation to replace or supplement the Nagoya Protocol. In addition, we expect that the speed of innovation in the plant breeding sector will reduce for a while due to the hampered access to genetic resources, but that thereafter the speed of innovation will most likely be compensated by development of new breeding techniques.

XB: Not so easy to see the future developments of the NP. In any case, some clarity will be needed.

To be confident into the future of our plant breeding, we need mechanisms where the access to the GR will be simple, fast and profitable for both the suppliers and users.

MB: In the future we expect a higher administrative burden will be placed on obtaining new Genetic Resources. This could have negative effects on innovation and cooperation. This might also negatively affect the goal to preserve and sustainably use biodiversity as a global effort.

TvdB: We expect that global research cooperation’s might suffer for a while, until the parties to the CBD realize the cause and have made alternative and better benefit sharing tools. An example of such a cooperation is ISHI-Veg, the International Seed Health Initiative for Vegetable Crops (http://www.worldseed.org/our-work/phytosanitary-matters/seed-health/ishi-veg/). Here the seed industry cooperates to develop methods for detection of infected seeds in commercial seed lots, thus reducing the risk of global spread of seed-borne diseases. Currently the exchange of samples of pathogens, and even the contribution of knowledge to this network is in some countries hindered by the domestic ABS-regulations.