The ETC Group shares its concerns over the three announced acquisitions

It is rare for any merger to be described, by the agreeing parties, as anything more than a modest technical restructuring beneficial to customers and shareholders alike. Actors in agricultural mergers have the added advantage of implying that their deal will, in some way, end hunger or at least contribute to greater food security. It was surprising, then, that the agreement between Bayer and Monsanto last September attracted so much international concern. Bayer management, both in announcing the agreement and in the media ever since, have played the world hunger card, but even the acquisition-acquiescent financial press allowed that there could be justifiable concerns for food security. The concern, of course, is because the Bayer-Monsanto hookup was the third merger announced over a matter of months bringing together the biggest players in seeds and pesticides. The first deal, between ChemChina and Syngenta, stirred some interest mostly because the bid was by a Chinese company, not one of the Big Six Gene Giants. The second bid joining Dow and DuPont was less surprising but mostly stirred industry interest because it pretty much guaranteed that Monsanto, Bayer and BASF would also be forced into the market to shop for partners.

Emergency debate

A few weeks after the Bayer/Monsanto news, the Civil Society Mechanism (the assemblage of Civil Society Organizations – CSO) participating in the UN Committee on World Food Security (CFS) in Rome called for an emergency debate on the concentration of the seed and pesticide industry and, more widely, for the oligopoly implications of corporate concentration for world food security. The civil society request was pro forma– no one was surprised by the CSO demand and no one expected the highly political intergovernmental committee to accept. Governments don’t like being railroaded and last-minute changes to agendas are easy to block. To everybody’s amazement, the committee’s chair, Sudan’s Agricultural Minister, supported the call transforming the weeklong meetings into a series of skirmishes by those for and against a debate on the mergers. The G-77 and China (the global South) was sympathetic to the debate, but most unexpectedly, Australia and Canada were also sympathetic along with Iceland (whose delegate is vice-chair to the committee). The US and France were flatly against changing the agenda. France, with a penchant for protocol, was afraid of setting a precedent that could fracture the political but surprisingly collegial style of the CFS. Predictably, the US argued that governments were “unprepared” for an emergency debate. The argument was ill advised. The CFS arose out of the food crisis of the mid-1970s that forced the world’s first-ever emergency World Food Conference in 1974 where heavy weight political actors like Henry Kissinger flew to Rome to intervene in the crisis. Recognizing that food shortages had caught governments off guard, Kissinger and others pressed for a series of institutional changes, including the formation of the Committee. In other words, the CFS, with an unusually open mandate and annual sessions, was to be the UN’s early warning mechanism on issues of food security. Blocking the debate imperilled the CFS’s mandate and threatened the precedent France wished to avoid. Nevertheless, the US and France prevailed, and the emergency debate devolved into a side event for delegations in the Malaysia room. The debate’s proponents were still encouraged that the meeting was jammed with delegations, including the CFS chair and vice chair, and governments appear to recognize that the CFS would fail its mandate if it didn’t create space for such debates in the future.

ChemGen Industry

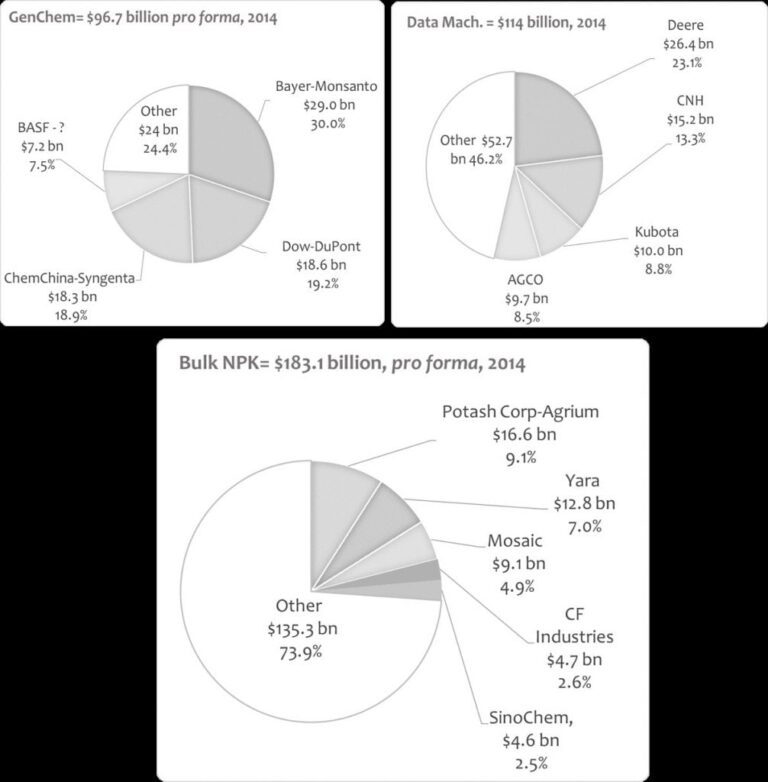

So, why the fuss? If all three proposed deals go through without significant divestitures, the three companies left standing, together, will control more than two thirds of the global commercial market for seeds and pesticides combined. If we add BASF, the most likely beneficiary of any divestitures, then four companies will have more than 75 per cent of the combined seed/pesticide market. ETC Group argues that completion of these three deals confirms that the global commercial seed and pesticide markets have merged into one – best described as the ChemGen industry.

Concentration along these first links of the industrial food chain should trigger anti-competition concerns around the world. The merged entities ring the alarm bells for regulators using the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) as well as those using the CR4 standard (where the four-company market control exceeds 60 per cent or, sometimes, two thirds). The application of either standard should be sufficient to stop the deals. While it is the global power of the companies that is most concerning, the crop-by-crop measurement is also alarming. Whether it is canola in Canada or maize, soybeans or cotton in the USA, the three leading ChemGens break the rules. Indeed, but the only way policymakers can admit the deals is by changing the measuring stick, going to CR2 (CR3’s ship has already sailed).

Because we are not talking about widgets but World Food Security, not only should the deals be blocked, the whole issue of corporate concentration the industrial food chain should be on the table for debate. Specifically, this October’s meeting of the Committee on World Food Security should have this issue squarely on its agenda and be prepared to initiate a study by its High-Level Panel of Experts. Likewise, UNCTAD (the UN Conference on Trade and Development) should be encouraged to accelerate its research on anti-competition policies including the option to establish a UN Treaty on Competition Policy. When the UN’s Science and Technology for Innovation (STI) Forum convenes in May this year, its review of the Sustainable Development Goals for agriculture should include consideration of mega-mergers in the industry. Later this year, when the FAO Seed Treaty convenes in Rwanda, it would be a dereliction of duty for governments not to consider the implications of these mergers for plant genetic resources.

The merging companies can, of course, argue that their share of the global market is actually modest and, ‘sadly’ may not have any direct advantage or disadvantage for so-called smallholder producers. Peasants, the smallholder farmers who feed 70 per cent of the world’s people, source, 80, 90 per cent of the world’s annual seed supply outside regulated commerce, from their own bins, those of their neighbours, or via barter in local markets, far from Bayer/Monsanto, Syngenta/Chem China, or Dow/DuPont. Likewise, peasants either don’t want, or can’t afford, pesticides. As the fertilizer industry keeps telling us, half of the world’s food is produced without their product. Thus, some might argue, most of the world’s critical food supply could be untouched by the mega-mergers.

Influencing the policies

Intentionally or not (and it is usually intentional), big companies have a disproportionate influence over national and international agricultural policies and practices. Between the First and Second World War, for example, General Electric sought to expand the market for its radiation technology by moving into plant breeding and inducing mutations through radiation. Their influence was sufficient to induce President Eisenhower’s “Atoms for Peace” initiative in the 1950s, and the formation of the Joint International Atomic Energy Agency breeding program with FAO, which has bumbled on for more than 50 years wasting money and distorting plant breeding research and technology transfer programs throughout Africa, Asia and Latin America, long after General Electric gave up on the idea. Likewise, when Standard Oil of New Jersey (now ExxonMobil) following World War II sought synergies in the use of fossil carbon to make and market fertilizers and pesticides and, more as collateral damage than anything else, included seeds in their business model as well. The result was a distortion of the Green Revolution toward seeds that welcomed or required fertilizers and pesticides. Standard Oil got out of this pretty quickly but peasant agriculture has been paying its price ever since. Enthused by the same Green Revolution and Norman Borlaug’s Nobel Peace Prize in 1970, the world’s largest oil and chemical companies saw the potential for a global agricultural input market subsidized by governments and bought into both seeds and pesticides. For a brief time in the 1970s, Royal Dutch Shell was the world’s largest seed company. Occidental Petroleum, Atlantic Richfield and others also bought companies. When the they bailed out a few years later, they had still contributed to the transformation of agricultural inputs by either buying out or wiping out hundreds of small family seed companies, strengthening international property monopolies over plant varieties, and creating a (sometimes hallucinogenic) “high-tech” image that convinced both small companies and the public sector that companies had to be big, have deep pockets, and a capacity for risk if they were to do plant breeding in the era of new Biosciences.

GMO’s

While we might all be tempted to get into a fight over GMOs right about now, I would argue that GM cotton, canola, soybeans and maize have done nothing for national or global food security. One of the least considered impacts of GM crops has been the decimation of public sector agricultural research and the reorientation of virtually all public and private research toward the GM platform to the exclusion of exciting alternatives. By and large, public sector has become “cheap labour” doing the work the private sector doesn’t want to risk or doesn’t need to pay for. This destruction of public goods is a burden that will haunt us all in the decades ahead as we struggle with climate change.

History is important because whether the latest mergers are commercially successful or not, they will have established a policy precedent accepting this staggering scale of corporate control. The shareholders will move on but the stakeholders, those who grow food and those who eat it, will have to live (or not) with the consequences.

Scientific research

The financial media and some policymakers have expressed concern that the deals on the table could lead to a reduction in scientific research. After all, if competition is reduced, why invest in expensive, high-risk R&D? Researchers like Jennifer Clapp at the University of Waterloo in Canada have noted that the three deals are basically companies with lots of seeds and few chemicals wanting to buy companies with lots of chemicals and few seeds, and vice-versa. Most of the companies are talking about R&D synergies, the code word for cutting research. The biggest savings come with reducing research on pesticides. It costs roughly $256 million to bring a new pesticide to market but it only costs $136 million to introduce a new GM variety. It is both cheaper and less risky to adapt new plants to old chemicals than to develop new chemicals for plants. Many are concerned that the world will see a decline in agrochemical research.

Gene-editing

With a certain convoluted logic, some proponents of the mergers have suggested that peasants, who don’t buy pesticides very much anyway, and environmentalists, should be delighted if the pesticide industry tanks. Not so. The waning fortunes of glyphosate have only encouraged the reintroduction of even more toxic chemicals. It is cheapest of all for ChemGen companies to bring back discarded old toxins (perhaps reformulated to the nanoscale to placate regulators and promulgate patents) than it is to develop new ones. As crops succumb to the pests and diseases that have mutated beyond the reach of the current chemicals, governments will be forced to grant exemptions (which never go away) to protect farmers and people from crop failures. This, admittedly, is a risky proposition, but profitable. In the longer-term, the new merged entities are placing their bets on untested new technologies, the next generation of biotechnology including gene editing, gene drives, etc. The theory is that so-called “synthetic biology” will create more resilient plants that can resist pests and diseases and surmount climate change with fewer and fewer chemicals. There is not, as yet, any evidence that this new suite of technologies is either scientifically sound or environmentally safe so society is being asked to gamble our food security with some of the world’s least-trusted companies. With three (or, at the most, four) ChemGens dominating the market and controlling the research agenda, policymakers are not just putting all our eggs in one basket, they’re throwing in the chicken as well. This not only impacts food security, it impacts the health of the agricultural workers who will be obliged to handle the pesticides and the health of the peasants adjacent to commercial fields and, of course, the people who have to eat the crop sprayed with pesticides.

So, the peasants who really feed the world, and don’t or rarely buy commercial seeds and pesticides, are still impacted by the mergers in many ways. Agribusiness CEOs have a lot more “face time” with agricultural ministers and prime ministers than local peasant organizations. Agribusiness business executives have privileged access to bilateral and multilateral trade negotiations while peasants hear about it on the radio after the deal is set. Corporate breeders may not want to jail farmers for using their seeds but the fallout from UPOV’91 and patent laws can devolve into national legislation that criminalizes peasants for exchanging, or even saving, seed. ChemGen pressure on policies ranging from input subsidies to public research to rural infrastructure can have collateral damages that imprison farmers and imperil livelihoods; the bigger the company, the louder their voice.

It is wrong to look at the immediate deals as the final round. If these deals go through, and that’s highly debatable, then the signal is given that not only is this level of concentration acceptable, even in the food system, but, that other levels of vertical and horizontal integration might be possible.

The Box

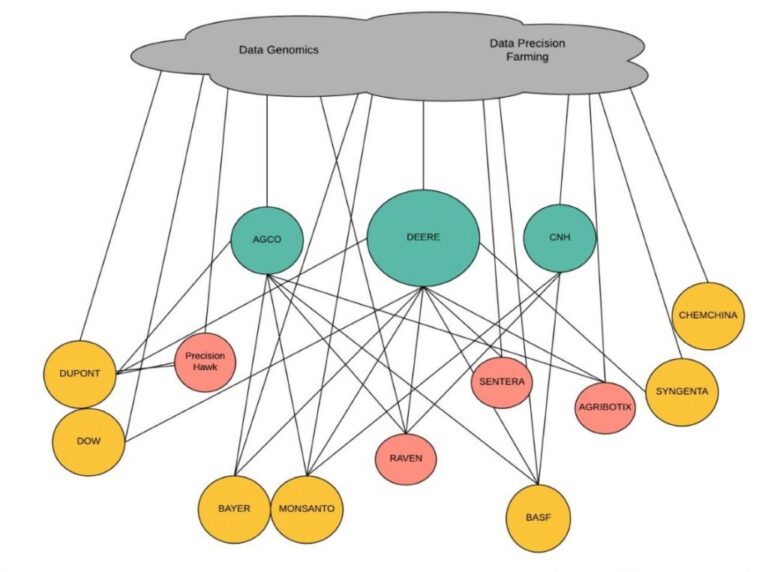

ETC Group is concerned that if the current round of deals goes through, there is enormous technological and commercial logic for the farm machinery industry to merge with the surviving ChemGens.

At least since the new millennium, the dominant farm machinery companies have invested heavily in satellite and sensor information and Big Data management. With this data, the machinery companies stand to know more about the inputs and outcomes of every field than any other company and even the farmer. Machinery companies have the “box” in which the other input companies have to put their seeds, pesticides and fertilizers. The same machinery company, and/or its satellites and drones, may be on the field several times during the growing season and the same company has the “box” that collects the harvest. Information technologies are making it possible for the machinery sensors to know exactly what is going into the field and what is coming out down to a few square centimetres, and to connect that information to previous growing seasons, current markets, and projected weather forecasts. This information also positions the companies to make the best deal (and conditions) for farm insurance. The machinery companies Big Data also aligns with the Big Data being pursued so aggressively now by ChemGens.¬†¬† Not to suggest that digital DNA is identical to weather forecasting, but they do have the field, the food and the farmer in common and their Big Data meets in the same cloud.

Farm Machinery

The farm machinery companies are also giants. The world’s largest, John Deere, has sales that approximate the global commercial seed industry. It is only if the three deals go through that the surviving ChemGen could be of a scale that could match the top farm machinery companies. The CR4 for farm machinery companies is about 55 per cent. This figure still lurks below the horizon for many anti-competition regulators and could make a sideways move into seat and pesticides manageable. And, despite their size, the machinery majors are not popularly known. Machinery doesn’t raise the same hackles as Monsanto, or pesticides. ¬†Since 2013, Deere and company has established joint ventures and/or other arrangements with each of the six Gene Giants now en route to becoming three ChemGens. Other major machinery companies such as CNH and AGCO have been making similar deals.

There won’t be a second round of machinery mergers until the current merger is played out. A move might be two to five years down the road or even further. But it is reasonable…and the reason for us all to be worried now.

Of course, discussion about a future massive round of mergers based on Big Data technologies is extremely unpopular with the input companies trying to get together now. This is not something they want talked about.

History has a lesson here as well. In 1981, ETC Group (then called RAFI), seeing the takeover of seed companies by pesticide and pharmaceutical companies, warned that the research strategy of the companies might be to create a co-dependence between their proprietary seeds and their proprietary chemicals. The companies were livid. Beyond the companies, science journals and agricultural societies insisted that, if not scientifically impossible, any hookup between a plant variety and a herbicide would face enormous technological and market barriers and farmer hostility. Ciba-Geigy (remember them?) invited me to Basel to show me the error of my ways and the scientists at Sandoz told me that the only market for an herbicide tolerant plant variety might be for Johnson’s grass in Texas. Now, we all know the data on herbicide-tolerant GM varieties.

Follow the money

To be clear, ETC wasn’t really following the science, we were following the money. There were lots of other sound reasons why pesticide companies would buy seed companies. But, one of the logical options facing an R&D driven firm was to investigate the commercial benefits of linking their seeds to their chemicals. In the end, the money led the way and the Science and Technology followed. As it was with Ciba-Geigy and Sandoz so it might become with John Deere and Bayer/Monsanto.

A bridge too far

Can the deals be stopped? Yes. The three deals together are a bridge too far. Every day they draught more and more attention from both the public and politicians. While we may, or may not, be able to alter the mergers in Brussels or Washington DC, three developments may ultimately block the mergers. First, the growing alarm for food security may compel policymakers to act to strengthen anti-competition policies and even to undertake a full review of the agricultural input sector with the potential to roll back agreed-to deals and break up monopolies. Second, the international community may take up the proposals of UN agencies like UNCTAD and begin the arduous work of establishing a UN competition office. The Trump Administration in the United States (US) inadvertently makes this option more plausible because no government expects the US to be part of any new international treaties and no one trusts the US to do an adequate job regulating itself. In this highly negative political environment, the UN becomes an attractive forum where other governments can act without US intervention. Thirdly, G-77 countries have their own anti-competition offices in every right to block the mergers within their own sovereign territories. Emerging markets, Brazil, Argentina, China and India, account for one third of global pesticide sales and that’s the growing part of the market. If one or two of these countries say no to the mergers, shareholders may get cold feet and force management to back off regardless of what is being agreed in Brussels and Washington. In fact, even a handful of small countries in any region of the world could catalyze opposition that will spread to much of the global South. Opposition from small countries doesn’t have to happen immediately. It can roll out over many months, but its impact could be cumulative and devastating. They could also force other governments in countries to agree to establish an international treaty in order to placate opponents. Politicians never get points for supporting corporate concentration but they do get points for opposing Monsanto. The story is far from over.

By Pat Mooney, ETC Group