Members of the EU FFC coalition share an inside view.

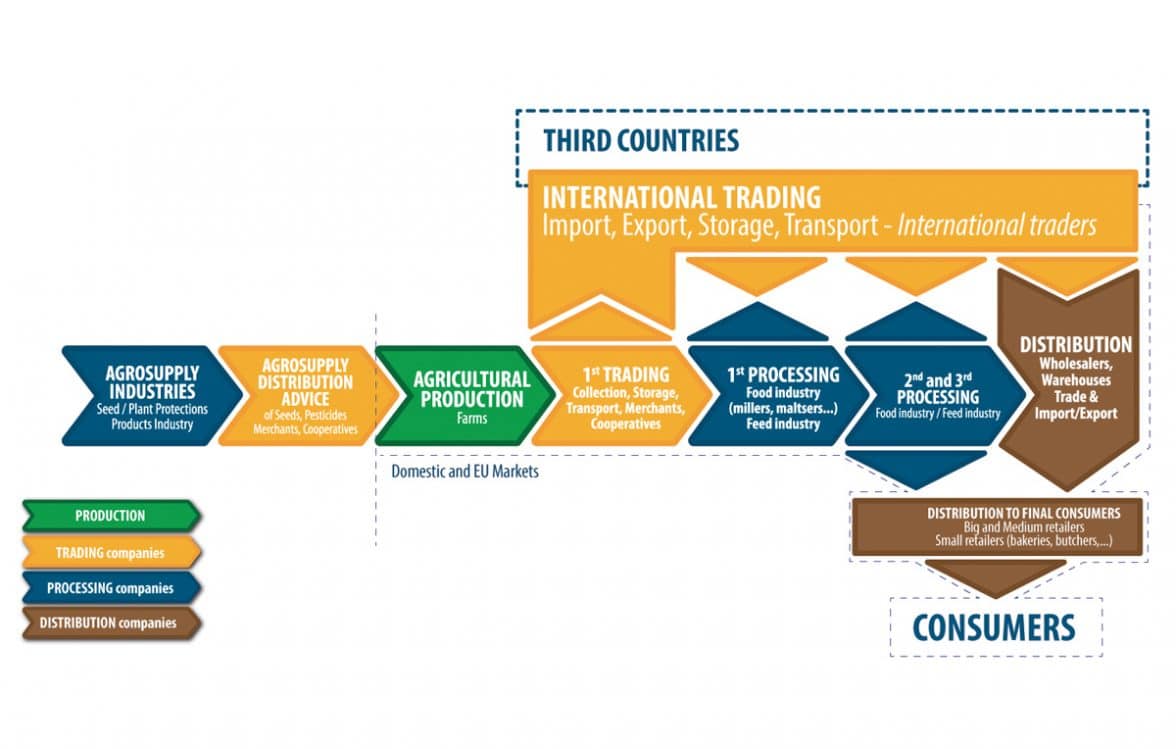

Who is the EU Food and Feed Chain coalition? Perhaps a more suitable question would be ‘why the EU Food and Feed Chain (FFC) coalition’? In short, this group of EU stakeholders teamed up as a result of the rapid developments in the area of regulation and use of modern biotechnology, both in general and in terms of specific genetic modification in plant breeding, seed production, farming, and food and feed use.

The members of the FFC coalition work together to address the specificities of the use of these technologies in light of the distinct national or regional regulatory approaches in several parts of the world, which have a unique and unprecedented impact on the EU agri-food chain.

In this sense, the EU FFC coalition represents different parts of the food and feed chain whose members are directly impacted by EU policies related to Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs). The FFC coalition gathers EU stakeholders involved in seed production and farming, and trade and downstream use of agricultural commodities and rice to elaborate practical, non-discriminatory and science-based proposals with a view to minimise existing and potential future impacts on cultivation and trade, as well as to ensure legal certainty and the freedom to operate for all industries concerned.

In particular, the FFC coalition brings together 14 organisations, notably the Association of Poultry Processors and Poultry Trade in the EU; European Association of Cereals, Rice, Feedstuffs, Oilseeds, Olive Oil, Oils and Fats, and Agrosupply Trade (COCERAL); Copa and Cogeca; European Seed Association; EuropaBio; European Flour Millers; European Vegetable Protein Association; the federation representing the European Vegetable Oil and Proteinmeal Industry (FEDIOL); European Feed Manufacturers’ Federation (FEFAC); Federation of European Rice Millers; FoodDrinkEurope; Starch Europe; European Livestock and Meat Trading Union; and Unistock Europe.

Throughout its busy years of existence, the FFC has been active on a number of fronts. Today, one of the most challenging questions on the table relates to the European Commission’s legislative proposal to give individual EU Member States the flexibility to legally restrict (or even prohibit) the import and use of authorised GMOs for food and feed on their territories. For ease of reference, this proposal will be referred to as the GM opt-out proposal.

How Did We Get Here?

The GM opt-out proposal was tabled after the president of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, drew political attention to the GMO approval system in the EU—arguably motivated, at least in part, by the media and political uproar in the aftermath of certain rulings of the European Court of Justice concerning GM maize 1507. As illustrated by Juncker’s statement below, the proposal is an open attempt to translate a political wish into the technical level.

“I also intend to review the legislation applicable to the authorisation of GMOs. To me, it is simply not right that under the current rules, the Commission is legally forced to authorise new organisms for import and processing even though a clear majority of Member States is against. The Commission should be in a position to give the majority view of democratically elected governments at least the same weight as scientific advice, notably when it comes to the safety of the food we eat and the environment in which we live”, said Juncker in his Political Guidelines published 15 July 2014.

As they stand, the rules for the authorisation of GM crops for food and feed use provide that each individual GM crop be authorised before being imported into the EU. This requires an extensive scientific risk assessment by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) to ascertain its safety, followed by a strict risk management procedure where Member States individually and jointly provide an opinion on the granting of the authorisation through two rounds of voting.

If Member States fail to obtain the necessary majority to either support or reject an authorisation, the Commission is compelled by the EU Treaties to formally adopt a decision. This is a system that, therefore, weighs Member States’ individual positions in view of reaching a common decision to authorise imports of GMOs. Although always a sensitive area, when this system was democratically agreed upon by the European Parliament and Council in 2003, it was considered in line with the utmost respect for democracy and the founding principles of the EU, including the internal market.

Since its adoption and implementation more than a decade ago, Member States have been unable to obtain a qualified majority in favour of or against any authorisation. This de facto compelled the Commission to formally adopt the authorisations in every case. While the functioning of comitology rules gathers no particular attention in other regulatory areas, the special sensitivity of GMOs triggers strong criticism and political opposition, which explains President Juncker’s alleged democratic deficit and the Commission’s proposal to try to address the political conundrum.

The Proposal in a Nutshell

Notwithstanding the current rules to authorise GMOs for food and feed purposes, with its draft, the Commission is proposing to permit that individual Member States be able to opt-out (i.e. be excluded) from such authorisations—something that is granted at the EU level. In principle, opting-out measures ought to be based on factors other than risks to human and animal health and the environment, comply with the EU’s international trade obligations (notably, its commitments under the World Trade Organization) and be in line with internal market rules. In fact, the proposal mirrors a parallel scheme affecting cultivation of GMOs in the EU since April 2015.

At the time of writing this article, the draft was tabled a year ago, and it has undergone a number of legislative steps.

EU FFC Partners’ Views

The FFC coalition has clear views on how the EU’s GMO system should be strictly science-based, predictable and timely, and in line with legislation already in force. The FFC partners have gathered substantial evidence and rely on solid arguments to support their views that the GM opt-out proposal is very far from meeting the needs of the EU agri-food chain in view of maintaining (if not enhancing) its competitiveness.

It is the opinion of the FFC coalition that, if adopted, the GM opt-out proposal would result in substantial commercial and legal risks for operators, condemning those to overly high costs and undue trade disruptions. The agri-food chain is the largest employer in Europe today, providing 44 million jobs. Threatening its competitiveness would be openly running against the EU’s political priorities of ‘jobs and growth’ and ‘better and smart regulation’.

From a procedural standpoint, the FFC partners regret that neither stakeholder consultation nor impact assessment was conducted. They note that the proposed system would create a dangerous precedent to lawfully contravene the founding principles of the EU whenever expedient in the future. Dismantling the internal market would also destabilise the commodities market in the EU and have a negative impact on the EU budget and its economy.

To better assess the possible implications of the proposal, selected members of the FFC coalition conducted an Economic Impact Assessment to analyse the potential adverse effects that look poised to arise in the event that four Member States opted-out within the terms of the proposal. COCERAL, FEDIOL and FEFAC’s analysis describes a scenario where France, Germany, Hungary and Poland deliberately opt-out from GM authorisations for soybeans. Given that these countries represent around 30 per cent of the European soybean demand, and that the vast majority (approximately 90 per cent) of soybeans and its derived products used for feed in the EU are GM, this worst-case scenario would no doubt have severe implications.

The Economic Impact Assessment takes stock of the fact that, from a global viewpoint, the EU is highly dependent on imports of protein-rich raw materials and products thereof for crushing and feed purposes, mainly—but not limited to—oilseeds and meals.

These protein-rich agricultural commodities are mostly GM-derived, a feature that brings no added value per se—at least in most cases. The nutritional characteristics of such GM crops are equivalent to those of their conventional counterparts. However, enjoying unrestricted access to a protein-rich supply on the global market is absolutely crucial to ensure the viability and competitiveness of the EU agri-food industry—as the EU does not (and for a number of reasons cannot) domestically produce sufficient protein crops to supply the demand.

The Way Forward

Despite the FFC partners’ opposition to the proposal, the impact analysis of its potential implications has proven a rather useful exercise for the EU agri-food chain to speak with one voice and demand that efforts and resources be put at the service of the single most important goal: making current EU decision-making work. As gathered at the FFC coalition, the concerned industries agree that the solution to the GMO authorisation problems can only be found in a timely and accurate implementation of the current EU rules—which keep scientific considerations at the heart of the authorisation system, and take into account the views of democratically-elected governments.

The members of the FFC coalition are convinced that it is critically important to preserve the core values of the EU, the single market and free circulation of goods, also in GMO decision-making. Authorisations must be strictly science-based, and be granted in cases where they are in line with EFSA’s independent risk assessment. GMO approvals need to comply with the EU’s international trade commitments in order to secure the smooth functioning of global trade relations with commodity-exporting countries, essential to ensure the present and future competitiveness of the EU agri-food industry. As net importers of agricultural commodities, EU operators along the food and feed supply chain must be able to compete internationally.

Last but not least, the legislative and regulatory environment in the EU needs to provide the much-needed legal certainty for economic operators. Clearly, that is the only way forward to secure the economic viability of key industry sectors, attract investment, and create growth and jobs in Europe.

In light of the need for a clear and consistent harmonised system, ensuring availability of agricultural commodities at affordable costs in the EU and legal certainty for EU business operators, the EU food and feed chain partners jointly call for an accurate and correct application of existing EU legislation on GMOs away from ‘creative’ schemes that risk undermining core European values.

Procedural milestones of the GM opt-out proposal

- 22 April 2015: The Commission tables its legislative proposal.

- 13 July 2015: Initial Member States’ feedback at the EU Agriculture and Fisheries Council.

- 13 October 2015: The Parliament’s ENVI Committee rejects the proposal. The Committee of the Regions also recommends to reject the text.

- 28 October 2015: The Plenary of the Parliament rejects the proposal and requests a new draft from the Commission.

Key findings of the COCERAL, FEDIOL and FEFAC Economic Impact Assessment on the European GM Authorisation Opt-out Proposal

- The amounts of GM-free soy that are de facto available for use in the EU are much lower than those that are ‘statistically’ available globally, mostly due to poor quality and commingling issues (i.e. the likelihood of traces of GM material despite costly segregation measures in place).

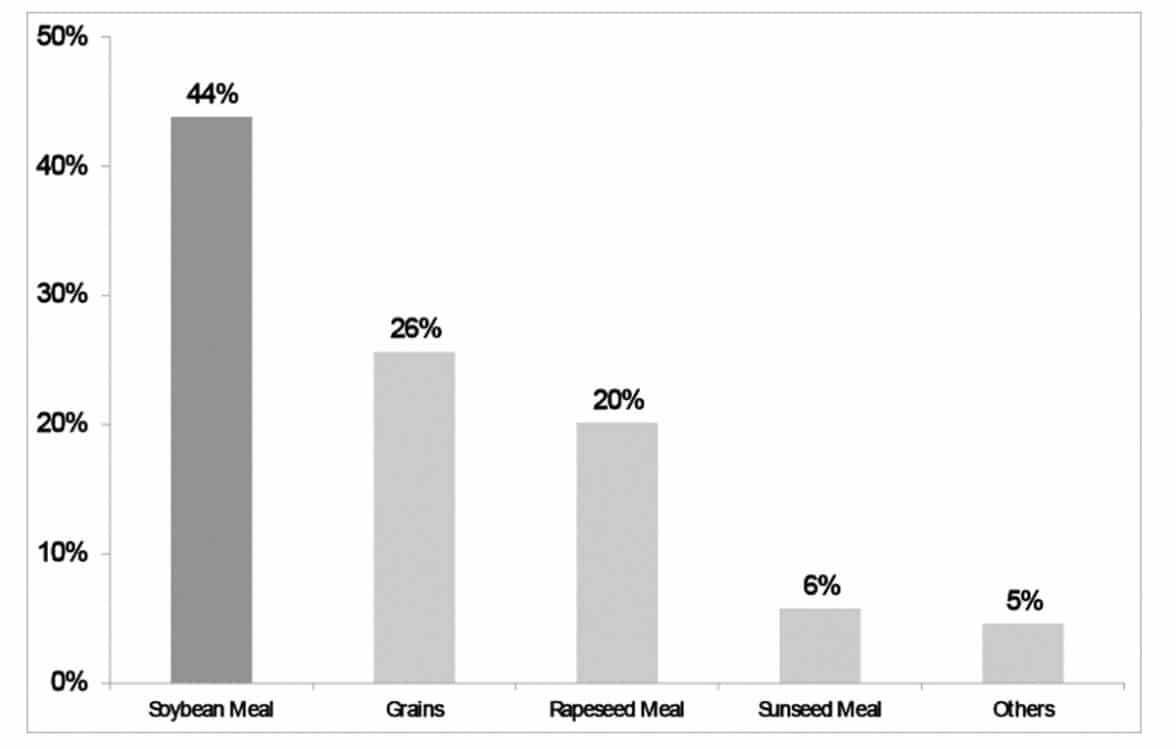

- Limited non-GM protein-rich feed material alternatives make the EU feed industry strongly rely on imports of soy. In terms of amino acid composition, soy is the most complete protein feed material on the market, and replacing the nutrients delivered by imported GM soy would require increased inclusion of other, less efficient, feed materials.

The Economic Impact Assessment Indicates …

On the average of the marketing years 2012/13 to 2014/15, the EU used 28.5 mln t of soybean meal for feed (i.e. 36.1 mln t in soybean equivalent). Out of this total, more than 35 mln t or around 97 per cent were imported. The four potential opting-out countries considered in the Economic Impact Assessment (i.e. France, Germany, Hungary and Poland) used 12 mln t of soybean equivalent. Given an average protein and lysine (an amino acid) content in soybean meal of 46 per cent and 2.8 per cent, respectively, soybean meal provides 4.4 mln t of raw protein and 265,000 t of lysine to the livestock sector in the above-mentioned four countries. This, in turn, means that soybean meal represents 32 per cent of the total protein and 44 per cent of the total lysine that is used by the livestock sector in the opting-out countries. In this respect, Figure 2 clearly shows the essential importance of soybean meal for the livestock sector.

- Considering that the GM opt-out proposal would restrict the currently existing choice between GM and non-GM food and feed (and related efforts from operators as a means of commercial differentiation) in opting-out Member States, the bulk of GM soy in feed would have to be replaced by non-GM soy at a premium. The premium can vary between EUR 44/t and EUR 176/t (i.e. 15 to 50 per cent of the value of the product). Considering the 2015 average premium (EUR 80/t), plus the additional costs at the compound feed stage (EUR 30/t), this would translate into an increase of costs for the EU livestock industry of around 10 per cent, leading to an additional EUR 1.2 bln if four Member States opted-out, or EUR 2.8 bln if the entire EU did so.

- The implementation of the scheme would inevitably result in a loss of competitiveness (and subsequent negative repercussions) for the livestock sector, both vis-à-vis non-opting-out Member States and third countries, and both at home and on global markets. The EU livestock sector would likely need to relocate, leading to a dramatic loss of competitiveness resulting in lower investment, income and employment generation in the sector.