The Anti-Infringement Bureau is protecting plant breeders’ rights in the vegetable seed industry.

Intellectual property is crucial for the seed industry, as it provides the necessary tools for return on the high risk and upfront investments that are needed to create a new plant variety. Unfortunately, infringements of IP rights are as old as IP itself.

Incorporated in Belgium in 2009, the Anti-Infringement Bureau (AIB) has seen many successes in combatting IP infringements in the vegetable industry. AIB’s mission is to protect breeders’ rights to vegetable seeds — AIB assists its members to prevent piracy and to pursue seed piracy cases.

In doing this, AIB helps to maintain the integrity of the plant breeders IP protection process in fairness to the tens of thousands of growers who are using protected seeds and who abide by respecting breeders’ rights, trademarks and copyrights.

“The initial focus of the AIB has been on ‘Greater Europe’, consisting of the EU and the Mediterranean Basin,” says Casper van Kempen, managing director of AIB.

At present, AIB has 11 members, although Limagrain — who counts as one member — has three companies enrolled. All members have an equal vote in the General Assembly, which normally meets twice a year.

Enforcement Decisions

AIB has the ability to file complaints with enforcement agencies regarding any observed and verified infringements, after consultation with the rights holder concerned. “This action has been taken many times in recent years in Italy and Spain, where very good relationships have been developed with enforcement agencies,” says van Kempen.

When a request is received from a member for AIB to take civil legal action, it is submitted to the board of directors. The board then decides to accept or reject the mandate request in accordance with its internal rules. The main criteria for this decision are:

a) Is the case linked to a generally occurring industry infringement problem? Specific examples of this category are: vegetative re-propagation of protected tomato varieties and other (grafted) crops; re-propagation of protected OP varieties like lettuce and beans; re-propagation of protected F1 crops (onions).

b) Is there a reasonable expectation for a successful outcome of the case in the jurisdiction(s) concerned?

c) Is a mandate of AIB valid under the jurisdiction(s) concerned? The decision to mandate AIB for legal action is an option for AIB members, but AIB is under no obligation to accept the mandate.

In Italy and Spain, AIB raised awareness among plant raisers and growers by filing over 40 legal complaints with authorities. In all cases the enforcement agencies fully cooperated and made inspections of the suspected companies. In Italy, AIB has a formal cooperation agreement with the anti-fraud unit of the Ministry of Agriculture. This agreement results in periodic exchanges of information and statistics on infringement and piracy.

In Sicily, the Guardia di Finanza inspected over 40 greenhouses after AIB submitted a report on the substantial losses in tomato seed sales due to vegetative propagation. In cases where infringement was proven by the test results of the sampled material, the enforcement agencies submitted their files with conclusions to the local courts for further follow-up by the prosecutors.

Another very important milestone is the incorporation of seed traceability and IP compliance of starting material in the new GlobalGAP version 5.0. “This is seen as a major step forward for our industry,” says van Kempen. “It also provides a concrete and cost-effective instrument for retailers and processors to check the integrity of their vegetable sourcing.”

Companies can do it alone, but it is complicated. Seven years after noticing the first signs of infringement, Dutch seed company Rijk Zwaan won a long-running infringement case against Italian company Agriseeds. After illegally reproducing the lettuce variety Ballerina RZ, the court of Milan ordered Agriseeds to pay Rijk Zwaan €205,701 plus legal costs. On behalf of Rijk Zwaan, company lawyer Marian Suelmann says she is happy with the result, especially since the number of illegal reproductions of vegetable crops seems to be on the rise. “Cases like this are undoubtedly complicated and time-consuming, but this example shows that fighting infringement in court can indeed be successful,” says Suelmann.

Unsuccessful Cases

Despite its successes at moving ahead with legal action, AIB has faced situations where it has decided not to pursue suspected cases of IP infringement.

In cases where the exposure in the market is judged to be detrimental to the commercial interest of the individual rights holder, it often decides not to pursue the matter. Therefore, companies have a strong preference to act jointly in addressing infringement cases, van Kempen says.

Other reasons for abandoning a case have been the safety of staff. “There is a strict rule never to release the name of informants in any procedure. However, in certain cases there is fear that the suspected infringer may draw his own — and wrong — conclusions and react. In case of any doubt on personal safety, it is a no-go for AIB,” says van Kempen.

The major factor preventing these cases from being successful, according to van Kempen, is the lack of an ability to mobilise field staff to report any suspicious activity. “The statistics show that only a very small percentage of the total of observed cases are reported.”

Many industries are fighting piracy and counterfeiting, but van Kempen says the vegetable industry is unique in terms of the challenges it faces.

“There are fundamental differences making our fight more complicated. In most other industries the pirates are third parties, which produce the illegal product and sell it as genuine product. The counterfeits are often of inferior quality, so the buyer and user of the counterfeit is often victim of the piracy,” he says.

Examples he gives are pesticides, spare parts for vehicles, and pharmaceutical products.

“In our sector, it is our own customers who are either the infringers — in cases of vegetative propagation and seed reproduction — or main beneficiaries, as buyers and users of the illegal starting material.”

From the documents found during a recent seizure at a company involved in lettuce seed piracy, it emerged that the financial benefit reaped by the lettuce growers, who had bought the illegal seed at very low prices, amounted to a very significant €900/hectare per production cycle.

“The fact that infringers are among our own customers often creates a loyalty dilemma for the sales reps. They are facing a situation whereby a person with whom they often built a relationship over many years is infringing the IP rights of his or her company. In these cases, it takes courage to confront the customer with this wrongdoing,” van Kempen adds. “Whereas in general, IP rights holders can rely on enforcement agencies — like customs agencies — to detect piracy, our industry has to rely much more on its own people for its detection.”

The other factor working against the vegetable industry, according to van Kempen, is that it can detect infringement only during the growing stage. Once the harvested product has left the grower’s facility, it is impossible to determine if it originates from an illegal source, as its physical characteristics and DNA are exactly identical to the legally obtained products. Therefore, inspections of the final product, as can be done in most industries, is not helpful in the vegetable sector.

“It is also quite common that sales reps observe infringements of the PVP rights of other companies. Once this happens, it is important that these cases are reported as well,” van Kempen adds.

He notes that this requires the infringement issue to be a fixed agenda item at sales meetings and periodic personnel review meetings. “It is important to overcome uncomfortable feelings about this subject, which often make people pretend it does not exist.”

To help AIB address this theme within its member organisations, Interpol offered its assistance in developing an e-learning module on IP rights in the vegetable seed sector, targeted at companies’ field staff and their interactions with growers and plant breeders, like sales reps, trial officers, customer service staff, and product managers.

This e-learning module will be initially available in English, Italian and Spanish, takes about 30 minutes to go through, and includes items like why IP rights are important; the various forms of IP infringements in the vegetable seeds sector; what to look out for when conducting your daily activities; and how to act when you see something suspicious.

Four past infringement cases are given as illustrations. At the end of the module a quiz has to be taken, and the results are automatically sent to the designated company’s sales director/manager for evaluation.

“In short, in the vegetable seed industry, infringement and piracy can only be overcome with the full support and mobilisation of the seed companies themselves,” van Kempen says. “They have the eyes and ears on the ground. Without this, even setting up a dozen more AIBs would not have much impact.”

Future Trends

When it comes to addressing the issue of IP infringement, van Kempen sees a number of challenges on the horizon.

“In countries that have more experience cracking down on it, we have the feeling that at least we put a hold on further growth of infringement. In Spain, with the help of Geslive, we have had a positive impact on the scale of illegal vegetative propagation of tomatoes. In Italy, the actions by the Guardia di Finanza and ICQRF in recent last years have at least made any potential infringer aware of the risks, and therefore much more careful. This seems to have at least contained the problem,” says van Kempen.

“In less-experienced countries with rapidly growing production, infringement is on the rise. This can be partly explained by a shift towards higher-value genetics. Also, the general level of technical skills is rising, opening the door to vegetative propagation. However, the paradox in these countries is that PVP is often a relatively young phenomenon, with very few varieties with PVP titles.”

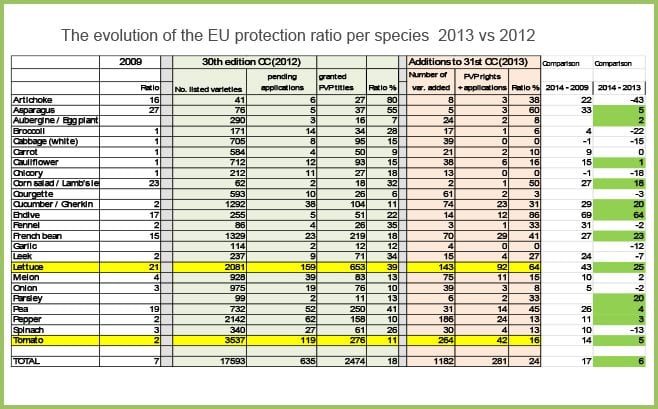

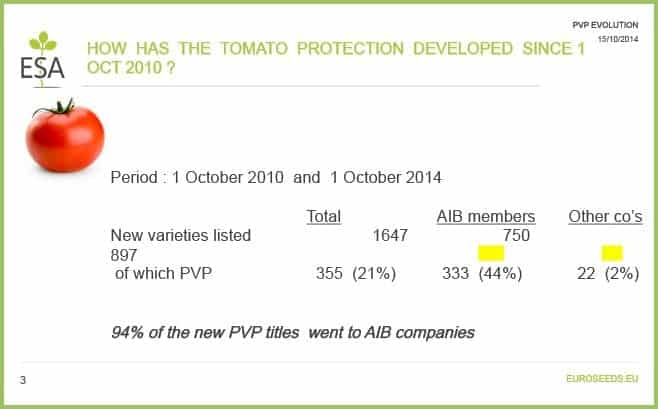

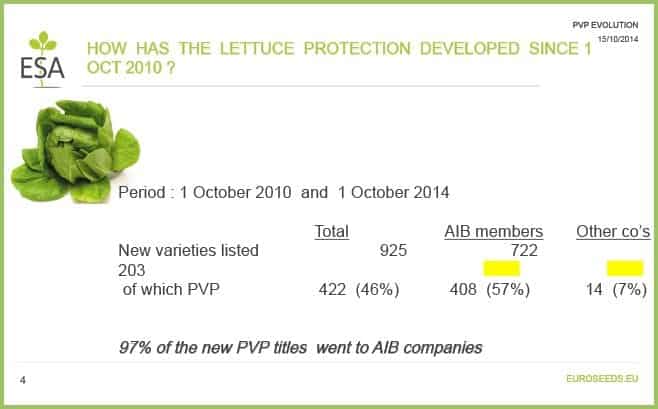

Another driving factor behind the infringement level is the level of protection, he notes. “It is striking to see that a very high majority of PVP titles in the EU is held by AIB members. The other companies hardly protect any of their varieties (see analysis made on evolution of PVP in tomato and lettuce).

Other countries from outside Europe are learning from AIB. In America, Seed Innovation and Protection Alliance (SIPA) was created a year ago. They are a joint venture between the vegetable seed industry and the field crop industry. SIPA does not copy the AIB model, and is more focused on educational outreach and not enforcement.

According to van Kempen, in order for an organisation like SIPA to be successful, an important qualifier is the commonly shared value about the importance of respecting IP rights. A strong feeling of common interest and collaboration will naturally result in the funding of enforcement action.

“It is a mistake to think that it is the legal department who has the main role in enforcing IP rights, rather than the sales force. IP protection should be embedded in a company’s entire organisation, with all departments and employees involved,” van Kempen says.

Rijk Zwaan hopes that the positive outcome of its case against Agriseeds will motivate other seed companies to pursue infringement cases, too.

“We have a common goal in protecting plant breeders’ rights, to ensure that seed companies are rewarded for their investments, which in turn are necessary in order to continue developing new and improved plant varieties,” says Suelmann.