This is one of our top stories of 2024, as we look back on the biggest newsmakers of the year.

Valerio Hoyos-Villegas is worried. The dry bean breeder and professor at McGill University is one of several researchers who conducted a recent study that found a shortage of scientists specializing in plant breeding. That could have serious consequences for global food security, including in Canada, as highlighted by new research spanning three continents.

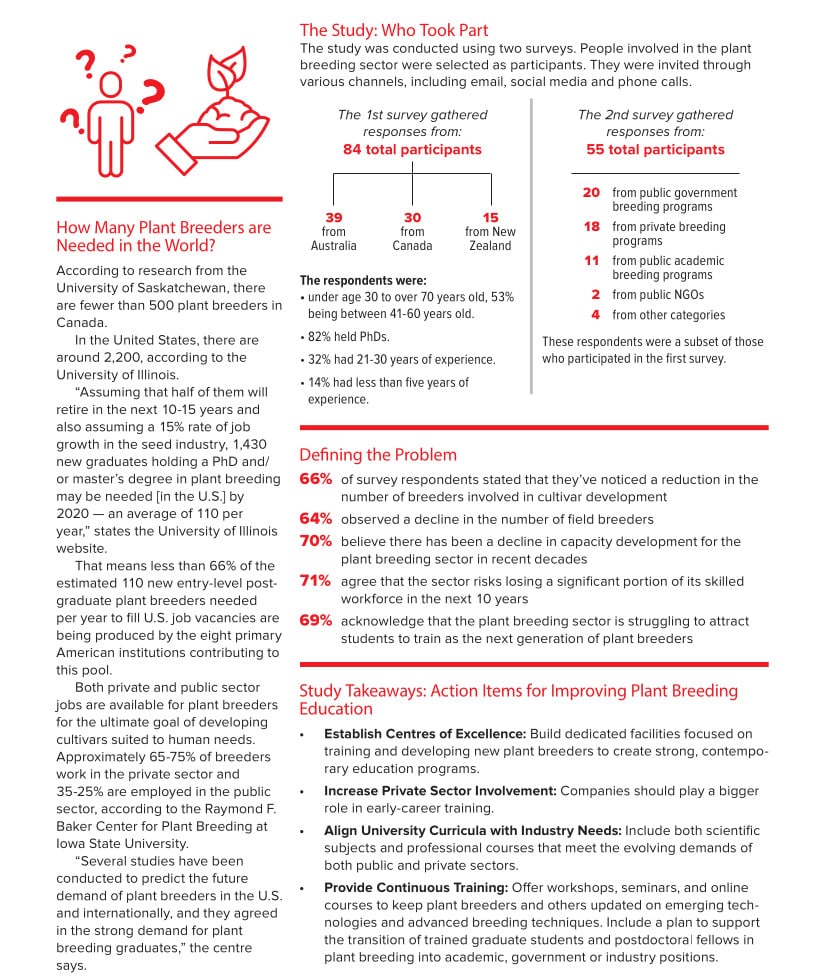

The collaborative study by McGill University in Quebec, Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) and Lincoln University in New Zealand sheds light on the critical shortage of plant breeding expertise, painting a worrying picture for the future.

The study emphasizes the urgent need to address this skills gap to sustain our current levels of agricultural, food, fibre, feed and fuel production. Consisting of two separate surveys, the study found a troubling trend: 66% of survey respondents stated that they have noticed a reduction in the number of breeders involved in cultivar development, while 64% observed a decline in the number of field breeders.

For Hoyos-Villegas, this perceived shortage in personal. He’s preparing to change positions and move from Québec to the United States, where he will lead the dry bean breeding program at Michigan State University (MSU).

“To be working in the agricultural research sector while facing a breeder shortage is definitely a challenge, but also an opportunity. Anyone stepping into this space would be in the perfect position to make a big impact,” he says.

The problem is nothing new. Lucy Egan, the lead author and a scientist at CSIRO, says the shortage has been escalating for a while.

“We’re witnessing a generational shift where highly skilled plant breeders are retiring, and new graduates are gravitating towards other areas of plant science like molecular biology,” Egan says.

Solutions

So, what can be done about it?

“Enhancing graduate programs in plant breeding and boosting private sector engagement are essential to keep up with the latest scientific and technological advancements,” Hoyos-Villegas says.

“Plant breeding must become part of the national agricultural agenda. We need to modernize facilities and train new plant breeders at a modern level.”

According to him, this isn’t a challenge that can be tackled in isolation.

“This requires cooperation between agriculture faculties, the federal government and other stakeholders. We all benefit from this because all new scientists — whether they end up in industry, academia, or creating new companies — start in academia.”

The impact of plant breeding goes beyond the creation of new crop varieties. Hoyos-Villegas points out that the field is tightly linked with technological advancement and the development of new industries, such as plant phenomics. In fact, it’s those new technologies that might be inadvertently leading to a shortage of field breeders, as students look to enter more technologically advanced areas of plant breeding and pass over traditional field breeding roles.

Many of those surveyed believed that there is less emphasis on field breeding in plant breeding training programs as technologies like genomics and data science become more prominent. Reasons they gave for this include the lack of secure positions and funding, and that so-called “traditional” breeding is perceived as a field that is not on the cutting edge.

“This perception is far from reality. Plant breeding is about advancing technology, improving the process of plant breeding and cultivar development, and importantly, fostering new industries. We need to have a conversation about modernization and upskilling, and that requires support at the highest levels,” Hoyos-Villegas says.

The challenge, however, is making this issue resonate on a broader scale. While the importance of plant breeding is undeniable to those within the agricultural and scientific communities, he acknowledges the difficulty of translating this urgency to the public. Yet, the solution lies in awareness and advocacy.

“This study aims to formalize the issue and bring visibility to it. We wanted to develop evidence that there is a dwindling trend in capacity, and it turns out to be very much true. Hopefully, this study will spark the necessary conversations and lead to real, practical steps to improve the situation.”