I had a great opportunity to spend eight months in Western Australia in early 2023 learning about agriculture production systems that local producers were using. The experience was an enlightening one that shed light on regenerative agriculture practices there and the similarities and differences between Canada and Australia.

The Wheatbelt in Western Australia covers an area from around Geraldton to Esperance to Albany. Geraldton to Esperance is a 1,100 km drive, an area slightly smaller than Western Canada, but with more diversity when it comes to climate ranging from very dry to almost rainforest conditions. Driving from Perth to Sydney is similar to driving from Calgary to Quebec City.

Most of the soils in the Wheatbelt are red-coloured sand, some “gutless white sand” that is granite based, with a few pockets of clay-based soils. The biggest difference is the weather patterns. In most of Western Australia, there are about four months where it rains from April to July, two months of infrequent rains in August and September, very little rain from October to February, then some showers in March.

Average yearly rain totals will range from 300 mm to over 900 mm, which mostly falls in under half a year. The biggest stress is that when it rains, it is cool, and when it is dry it can get very warm, 35 C to over 45 C for weeks on end. In Canada, at least we have the potential to get some moisture to get the crop started in the spring.

Canada vs. Australia

Seeding dates are similar in Western Canada and Western Australia. In Australia, seeding starts in the early parts of late March with most of the seeding occurring in late April and May. The difference is that in Western Australia, seeding can stretch out into July if rains come later. They do not have to worry about snow burying the crop, and that takes the pressure off. The concern would be running out of moisture for the crop as it matures as temperatures start to rise.

Main crops are wheat, barley, lupin and canola. Wheat and barley are by far the majority of acres. Some producers are playing with peas, chickpeas, lentils, flax (linseed) and triticale.

Harvest dates are also similar between the two countries. In Western Australia, harvest can start in August and the majority of the acres can be completed by October. The major difference is the lack of snow allows farmers to keep harvesting until harvest is completed. Delays in harvesting due to breakdowns, weather issues, and the rest of harvest delays are less of an issue. For the 2022 crop, harvest finished up in many areas in January 2023. This allows Australian farmers to get by with less harvesting equipment.

Canadian farmers sometimes think western Australian producers need to scale up to be more efficient. It’s not a good comparison to make. Capital cost per acre in Canada is considerably higher due to needing more equipment to get the acres covered in a fixed window of time as compared to Australian producers. Because there’s so much pressure to get the crop in the soil and harvested as efficiently as possible in Western Canada, we require the equipment and labour to get it done as quickly as possible.

That pressure is much less in Western Australia — one seeder and harvester will do many more acres over many more weeks. The farms I visited use well-maintained older equipment. We did not see many new equipment dealerships in our travels Down Under.

Research-Producer Gap

No matter where you farm in Western Canada, you will find a place in Western Australia that will look similar to home, until you look at the soil. They tend to get more moisture than most of Western Canada, but it is concentrated during their winter months when they are growing crops.

Many Australian producers spray herbicides to make sure weeds are not stealing nutrients or moisture. Herbicide resistance is an issue. Very few cover crops are being utilized and poly-cropping is just starting to gain some momentum.

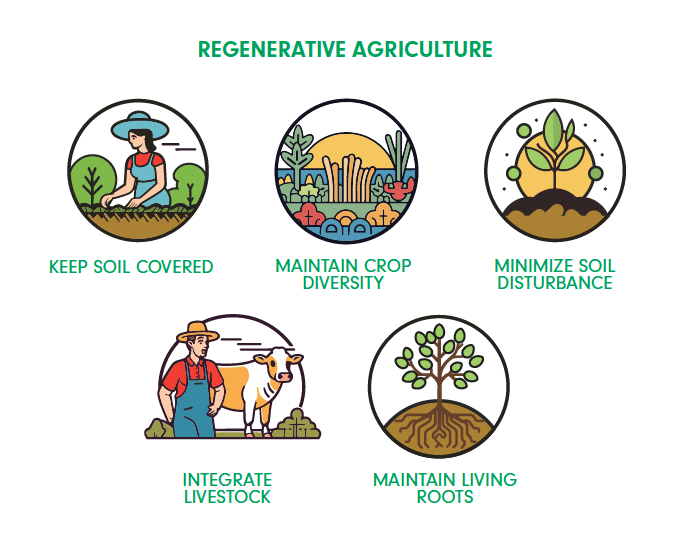

Farmers in Western Australia who try to manage their acres using regenerative practices have limited support to do so. Government does not have any programs to help producers or agronomists to adapt techniques.

Universities have limited research programs looking at systems approaches; many are linear reductionist thinking-type research programs. There are some great programs there and very forward-thinking minds, but there seems to be a gap in communication between the researchers and the producers.

Charles Massey’s book Call of the Reed Warbler has started some grassroots regenerative agriculture movements in Australia, especially in the East, and the movement is now is moving west. There are some groups that are active in regenerative ag, like water catchment groups, Regen WA, and Western Australian Livestock Research Council.

They have field days, educational meetings, and demonstration plots to raise more awareness of regenerative practices, but producers’ acceptance seems to be slow, with many seeming to be skeptical that change can occur.

It is difficult to find information sources in Australia to support regenerative agriculture, even though Australia is home to some world-leading producers and researchers.

There is hope on the horizon, though. The Australian carbon market will be a driver in producers using more regenerative practices as successful reports of producers getting paid to sequester carbon emerge.

Like in Canada, there are skeptical producers who just need more proof that regenerative agriculture works.

—Kevin Elmy is founder of Cover Crops Canada. His book Cover Cropping in Western Canada is available through Friesen Press, Amazon, and digitally through Apple Books, Kindle, and Google Play. For more info on Cover Crops Canada visit covercrops.ca