A new economic analysis shows the clear benefits that ratifying UPOV 91 has had for Canada — including growth in the number of Plant Breeders’ Rights (PBR) filings currently being seen by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA).

The 2015 amendments to the PBR Act brought significant changes to Canada’s agriculture, horticulture and ornamental sectors. A new economic analysis recently released by the CFIA reveals that these changes resulted in positive outcomes for various crops, including increased production, yield, farm cash receipts and export value.

The report Assessing Impacts of the 2015 Legislative Amendments to Canada’s Plant Breeders’ Rights Act and UPOV’91 Ratification shows a notable rise in the number of PBR applications after adopting UPOV 91, contrasting with the previous declining trend under UPOV 78.

“The findings of this report are overwhelmingly positive,” says Anthony Parker, commissioner for the CFIA’s Plant Breeders’ Rights Office. “It’s a testament to what can be achieved when we embrace change and seize opportunities.”

PBR serves as a vital form of intellectual property (IP) protection, with a mission to incentivize and reward innovation in plant breeding. These rights, granted by national governments, encourage investment and foster new plant varieties, ultimately benefiting farmers and consumers alike.

Unlike patents, PBR is exclusively reserved for new plant varieties, accompanied by benefit-sharing provisions that strike a balance between breeders and farmers.

In Canada, PBR has been governed by the PBR Act since 1990, offering protection to all plant species. In 2015, Canada took a significant step by amending its PBR Act to align with the latest international agreement, the 1991 Act of the International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV 91).

While anecdotal evidence suggests that horticultural and crop production sectors have reaped rewards from these changes, comprehensive quantitative data and sector-specific insights have been lacking.

The purpose of the new report is to examine the impact of strengthened IP protection since the 2015 amendments to the PBR Act, assessing the benefits for plant breeders, farmers, and the overall agricultural sectors. This study builds upon the initial 10-Year Review of Canada’s PBR Act (UPOV 78-based) report published in 2002.

The findings are expected to offer valuable indicators and insights for ongoing evaluation, shedding light on how breeding entities leverage enhanced PBR IP protection. Furthermore, the results may serve as evidence to support future regulatory amendments to Canada’s PBR framework, Parker says.

Fanfare for UPOV 91

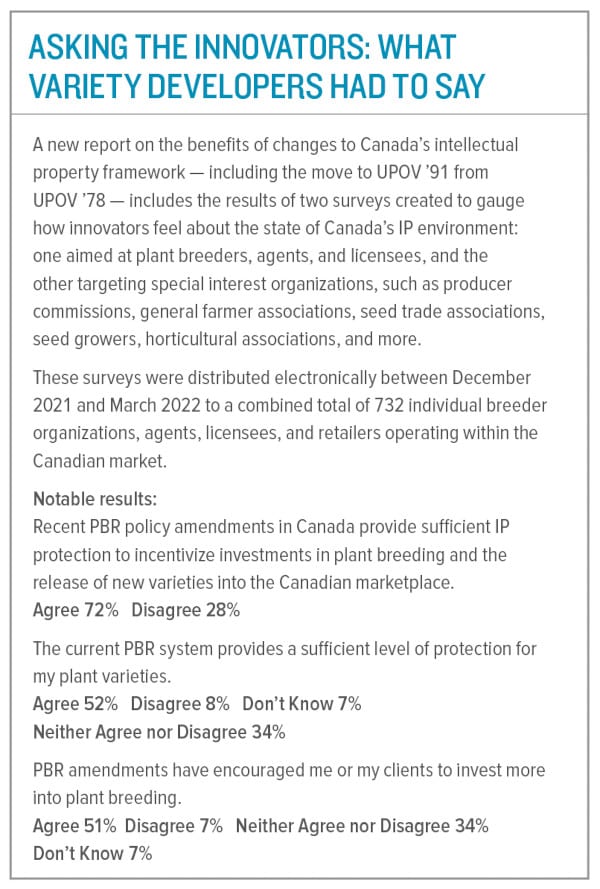

According to the report, stakeholder feedback — gathered through surveys and case studies — largely supported those amendments, which was conducted by JRG Consulting with assistance from Peter Philips and Stuart Smyth and the VALGEN Group.

Most respondents acknowledged increased investment in plant breeding and enhanced economic opportunities have been a direct result of the move to UPOV 91.

However, stakeholders also highlighted areas for improvement. Some called for extended protection periods for varieties with longer breeding and adoption timelines. Others argued that the “farmer’s privilege” should not apply to asexually propagated varieties, like fruit trees and ornamentals.

In addition, certain respondents in the grain sector emphasized the need for a value creation system to collect royalties on farm-saved seed or harvested grain, ensuring fair benefits sharing and promoting investment, innovation, and economic growth for both farmers and breeders.

Continued Growth in PBR Examinations

Parker highlights the record-high number of examinations — since moving to UPOV’91 —conducted in Canada’s agricultural sector that the PBR Office is currently seeing, emphasizing that it signifies a promising surge in innovation and competition.

He’s quick to point out that Canada is on an upward trajectory, and this growth indicates that innovation is indeed happening.

A PBR examination refers to the work carried out by PBR examiners who conduct field examinations for distinctness, uniformity and stability. These examinations are essential conditions for protecting intellectual property rights. Parker described how teams of experts travel across Canada and the U.S. from April to October, assessing various crop varieties.

“When we observe a high number of examinations and PBR filings, it serves as a clear indicator that things are progressing positively. Essentially, it suggests that we are moving in the right direction. These numbers signify that there is an environment of improved and equitable competition,” he says.

“It also signifies that Canada is becoming an attractive destination for testing and introducing new plant varieties, and perhaps even for investing in breeding programs.”

In essence, the rising numbers of filings and examinations tell a story of innovation happening, according to Parker.

“It’s a signal that there is genuine activity in the field. After all, if there were no significant innovations happening, there would be no need for people to seek intellectual property protection for their plant varieties. These increasing numbers provide encouraging evidence that innovation is indeed getting better in this sector, and that’s a promising sign for the industry as a whole.”

Positive Economic Indicators

The report reveals that various economic indicators showed positive results after the ratification of UPOV 91. These indicators included yield production, farm cash receipts, import and export volumes and export value. These outcomes suggest that the move to UPOV 91 had a beneficial impact on Canada’s agricultural innovation and competitiveness.

To gauge the perspectives of stakeholders, the study’s authors sought feedback from users of the Plant Varieties Protection (PVP) system, including breeders, licensees, agents, and retailers.

“Most of these stakeholders viewed the changes positively, believing that they stimulated greater investment and enhanced Canada’s competitiveness,” Parker says.

Special interest organizations, such as agricultural associations and producer commissions, also expressed positive perceptions of the move to UPOV 91.

Challenges Ahead

Despite the benefits UPOV 91 has had for the country, Parker says Canada must address specific challenges. One challenge lies in the need for stronger IP rights for crops with lengthy breeding and market acceptance timelines.

Another issue is the concept of “farmer’s privilege,” which may not be suitable for asexually or vegetatively reproduced crops.

“Establishing legal clarity on this matter is essential,” he adds.

Parker underscores the necessity of implementing a fair and balanced compensation system for farm-saved seed. He draws a parallel with authors’ rights — it would obviously be unfair to make copies of a writer’s books and sell them without compensating the author.

Yet, breeders are not adequately compensated when farmers propagate seed, essentially making copies of the innovation, without paying for it beyond that first certified seed purchase. Paradoxically, this is a widespread practice that is often staunchly defended. Without such a mechanism to fairly compensate breeders when growers choose to save the seed and plant it year after year, Parker believes Canada’s innovation and competitiveness will suffer for some crop types.

“While Canada has made progress, further strengthening IP rights is necessary to compete with global plant breeding superpowers, such as the United States and the European Union,” he adds.

He suggests that Canada can learn from innovative entities within the agricultural sector that have succeeded despite limited funding. Parker encourages a shift in perspective, focusing on outcomes, and adopting a more competitive and entrepreneurial approach to foster innovation in plant breeding.

Breeders and companies in the fruit, vegetable and ornamentals spaces stand out as innovators that have particularly benefited from Canada’s PBR environment, including the move to UPOV 91 — particularly ones that operate within the public sector, he adds.

He cites haskap (a berry crop bred by Bob Bors at the University of Saskatchewan), roses (bred by the Vineland Research and Development Centre in Ontario) and asparagus (University of Guelph) as areas where plant breeders have shown that PBR can be an asset to breeders and help them to thrive.

In all cases, Parker says innovation and the protection of IP have worked hand in hand to drive progress.

“I think there are valuable lessons to be learned from these examples. Instead of focusing on the challenges related to securing government funding, perhaps it’s time to take proactive steps that benefit both public and private institutions through greater partnerships with producers and a more collaborative approach,” he adds.