The COVID-19 outbreak led to concerns that seed supply chains would be disrupted and countries relying on imported seed would not have sufficient supplies for the upcoming seasons. A recent OECD report titled The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Global and Asian Seed Supply Chains looked at how the seed supply chain had been affected by the pandemic, with a focus on Asia.

“We focussed on the impact of COVID-19 from the perspective of seed companies and the formal seed sector and found out that the global seed sector was reasonably resilient during the crisis, although seed companies headquartered in the Asia Pacific region were more negatively affected than their counterparts in other regions,” says Csaba Gaspar, Program Manager at the OECD.

According to the study, the two main bottlenecks were the availability of staff in the seed production chain and in government administrations and the distribution of seed to farmers.

Annelies Deuss, Agricultural Economist at OECD explains, “If we want to build a more resilient seed supply chain, it will require policies to ensure the uninterrupted production and movement of seed during lockdowns; the further development of international seed supply chains; and the diversification of seed production.”

She notes that digitalization could also improve the availability of information on seed production and trade, enabling faster government responses to disruptions.

“It was good that many countries classified the food and agriculture sector (which includes seed) as ‘essential’, thereby facilitating the free movement of goods and allowing employees to continue working in this sector,” Gaspar explains.

“To better understand the impact of COVID-19 on the seed supply chain, we carried out a detailed analysis from the perspective of seed companies and we did this in cooperation with the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF), and we got great assistance from the International Seed Federation (ISF), the Asia and Pacific Seed Association (APSA) and the World Vegetable Center (WorldVeg),” says Deuss.

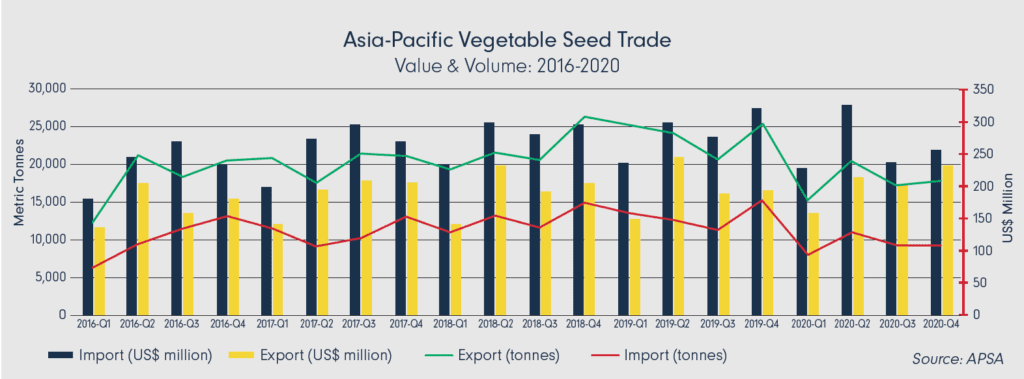

The report focused on vegetable seeds in the Asia Pacific region, which accounts for over half of the international seed trade in the region. The data for the report came from several online surveys of seed companies over the course of 2020.

The survey responses indicated that seed trade in the Asia Pacific region was negatively affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, and that recovery had been slow. Companies reported that seed demand had dropped, with the demand for vegetable seed falling behind other crop groups. This was mainly caused by finding appropriate freight solutions and many companies reported a negative impact for international seed shipments.

The survey results also show that seed companies with headquarters in the Asia Pacific region experienced a larger decrease in seed demand than their counterparts outside the region. In comparison to the rest of Asia, the survey results for Japanese seed companies indicated a less severe impact of COVID-19. The Japanese seed companies reported that by autumn 2020 they were not experiencing any major obstacles to importing seed.

“We wanted to draw up learnings for the future and extracted several policy recommendations from the data. Implementation of these measures will strengthen the resilience of the seed supply chain and mitigate or avoid the negative effects of the current pandemic and future crises,” says Gaspar.

Policy Recommendations:

- Ensure production and movement of seed during a crisis: It is crucial that the agricultural sector remains classified as “essential” in all countries to ensure the continued production and movement of seed during any crisis. At the same time, it is important to carefully consider any sudden changes to existing regulatory frameworks (e.g., certification and phytosanitary requirements, customs clearance) and prevent any technical barriers to trade when the relevant authorities are short of staff and under pressure, and thus cannot easily adjust to changing requirements. Communication and coordination between governments and authorities is even more important during a crisis to avoid interruptions in the seed supply chain.

- Support the development of international seed supply chains and the diversification of seed production: Most countries cannot sufficiently supply their farmers with seed of their choice with their own national seed production. Thus, internationally interconnected seed supply chains have considerable benefits for the majority of countries in terms of their economic stability and activity. The economic risks of nationalising seed production are higher than maintaining international seed supply chains and developing policies to mitigate the associated risks. Supporting the seed sector to diversify seed production in different locations worldwide is beneficial for the stability of seed supply and the availability of diverse varietal choice for local farmers. Government policies should focus on the support and further development of the international regulatory framework for seed production and trade. This would include active participation in the regulatory work of international organisations such as OECD Seed Schemes, UPOV, FAO and ISTA. Developing countries should be supported to develop their national seed sector in line with the international regulatory framework e.g., via capacity-building activities or twinning programmes. This could not only increase their potential to participate in the international seed supply chain as seed-producing countries but would also enable local farmers to access high-quality seed of modern varieties, delivering both local and global benefits. This has positive implications for food security, as well as for the incomes of seed-producing farmers and breeders.

- Support digitalization of the seed supply chain: The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated digitalization in many areas. In those countries where seed production and certification were supported by digital tools, the impact of disruptions to staffing and travel were less severe. Governments should support the digitalization of the international seed supply chain and should also aim to reduce the digital divide between and within countries. Inter-governmental digitalization initiatives may reduce these digitalization inequalities by providing a wide range of users with access to digital platforms. Increasing the digitalization of certain procedures in the seed supply chain, e.g., the seed quality or phytosanitary certification systems, and creating more open data policies would be a proactive step for policymakers to support more resilient seed systems.

- Ensure public availability of information on seed production and supply chains: Governments could take coordinated responses, including generating and sharing real-time data and implementing early warning systems which would allow them to react quickly to disruptions in the seed supply chain. Taking into account the specificities of the seed supply chain, the most realistic approach would be to collect information and trace ongoing seed production in different countries and share this information on an international platform. This would be particularly important in those countries where farmers have not developed a robust information system on input supplies.

“I’m happy to report that the OECD Seed Schemes are currently working on the digitalization of their varietal certification system, including the development of a database of ongoing seed certification activities. Once this system is developed, it has the potential to be the basis of an international data sharing platform of ongoing seed production in participating countries,” adds Gaspar.

Editor’s Note: This piece originally was featured on our sister publication’s site, European Seed. The full OECD report can be found here.