Mike Scheffel of the Canadian Seed Growers’ Association sheds light on our questions about the makeup of pedigreed seed acres in Canada.

Last week we offered a visual map of inspected seed acres by province. As we dig into data provided by the Canadian Seed Growers’ Association, we will gather insights into some recent pedigreed seed trends and the reasons behind them. This week, we offer some insights from Mike Scheffel, managing director of policy and standards for the CSGA.

In 2020 Saskatchewan overtook Manitoba with 340,621 total acres of pedigreed seed production. That’s a slight change versus 2019 when Manitoba topped Saskatchewan with 341,753 acres compared to Saskatchewan’s 2019 acreage of 330,067. Any thoughts on why Saskatchewan beat out Manitoba?

People just sort of pulled back from soybean production. More than 100,000 acres have disappeared in Manitoba over the last three years. For a while there, everyone was jumping on the soybean bandwagon. In 2017/2018, countrywide there were over 400,000 acres of soybean seed. And then, in 2019, it dropped from 401,000 acres to 318,000 acres. Since then, from 2019 to 2020, we saw another 45,000 or so acres disappearing there as well.

Also, Prince Edward Island’s total pedigreed seed acreage fell from 2,983 in 2019 to 1,820 in 2020 — a whopping 39 per cent decrease. Why such massive decreases?

Again, soybeans. They had no soybean production in 2020 due to production logistics changes in Canada.

Nova Scotia’s acreage declined significantly in 2020 (21 inspected acres) over 2019 (51 acres). That’s a big drop. What gives?

Nova Scotia is not a big pedigreed seed production area. Last year, we only had one CSGA member in Nova Scotia. In 2020, there were 21 acres of peas in the province, but in 2019, they had 51 acres. So they’ve fallen by more than 50%, but they’re falling from a very low level to begin with. Simply said, there’s not a lot of great agricultural land there, and much of the agricultural land that they do have is put into higher-value crops like apples. They grow a lot of blueberries there as well, and some potatoes. Nova Scotia farmers are looking to grow high-value crops on the limited acreage they have.

Of all the crops, lentil seed acres increased the most in 2020. Any idea why?

Lentils fluctuate quite a bit. In 2020 we had almost 39,000 acres of pedigreed lentil seed in Canada, but the year prior, only 26,000, and less the year before that. That’s likely due to some overproduction and price competition in seed versus commodity lentil production. Several years ago, I spoke with a seed grower who was frustrated because he had agreed to a contract early on to sell his seed for 90 cents per kilo or something like that, and the lentil crop was being bid up past 90 cents a kilo just for export. And he had the seed that he had to sell at 90 cents when he could have delivered it as a commodity crop for even more. These things often go in cycles.

With lentils, a lot depends on market conditions, with Turkey and India being big buyers. India will raise tariffs and lower tariffs quite often. They’re trying to protect their farmers and ensure that their local farmers get good prices for their domestic lentil production. They don’t want cheap Canadian lentils pouring in and undermining local farmers, as they understandably see it.

By contrast, wheat has stayed pretty constant, staying well above 350,000 acres of pedigreed seed in Canada for the past six years.

There are drivers which we often don’t think about. Midge tolerant wheat has been around for quite a long time, but as you know, you’re only allowed to save your seed for one year. Then you have to go back and buy certified seed the following year to maintain the proper ratio of the susceptible variety with the midge tolerant variety in the varietal blends they sell for midge tolerant wheat. So, as more and better midge tolerant wheats come along and more people decide to use them, it drives demand for certified seed a little bit because they can’t save their seed for three, four or five years. They have to go back to certified seed every other year. This has done quite a bit in helping maintain some of those acres of pedigreed wheat seed. Also, don’t forget that that AAC Brandon kind of exploded onto the scene about four or five years ago and was a bit of a game-changer that drove a lot of demand for wheat seed.

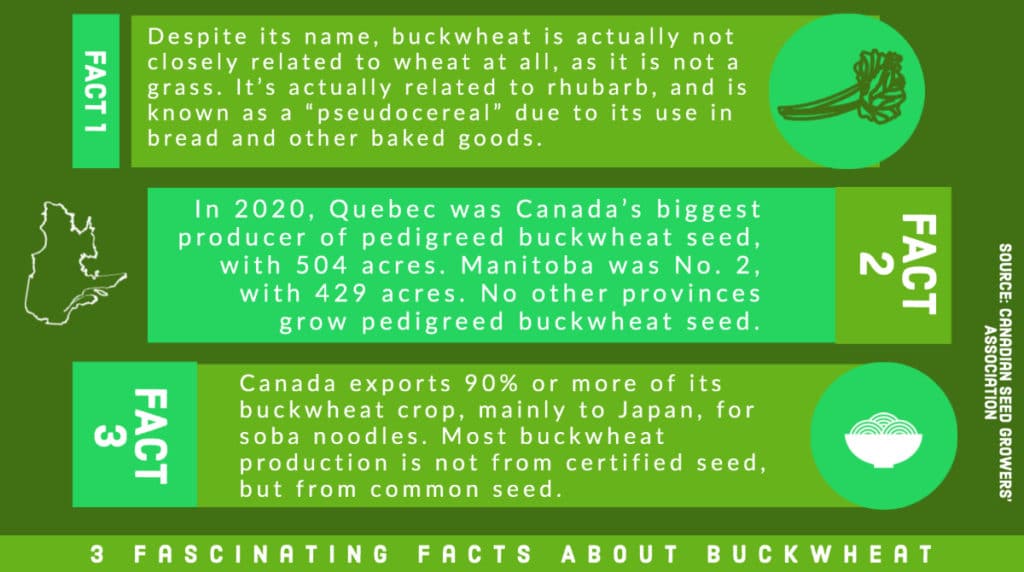

Of all the crop types, buckwheat fluctuated the least — down only 25 acres in 2020 compared to 2019. Is the market for buckwheat pretty stable?

Buckwheat is a pretty small crop. It has the fewest acres of any of the crop kinds outside of minor crops. We’re exporting 90% or more of our buckwheat crop, mainly to Japan, for soba noodles. Most buckwheat production is not from certified seed; I would expect a lot would be from common seed. Manitoba is a pretty big producer, although we see quite a bit being grown in Quebec as well. Interestingly, those are the only two provinces that grow buckwheat seed. Quebec may well be producing just for the domestic market. We do make our own soba noodles here to a certain extent, and buckwheat is included in various types of multigrain cereals and breads.