Clemson University researcher Sachin Rustgi searches for solutions to celiac disease.

Wheat has long history of challenges, ranging from drought to pests to diseases. Typical conversations about wheat breeding usually center on agronomic factors of yield and drought tolerance, but new food trends spell trouble for wheat’s future. Low-carb, gluten-free and protein-centric diets are bringing a greater challenge than the crop has seen before.

The war on gluten, the protein that gives bread, pasta and cereal it’s chewy or crunchy texture, is threatening not only farmers, but also the health of future generations. But Clemson researcher Sachin Rustgi’s new wheat variety research is proving that gluten might be more manageable than we thought.

One in 100 — worldwide, that’s the estimated number of people that have celiac disease, according to the Celiac Disease Foundation. When a person with the disease eats gluten, the body mounts an immune response that attacks the small intestine, causing nausea and digestive problems. More than 2.5 million Americans are genetically predisposed to the disease but are still undiagnosed, they estimate. And since it’s passed genetically, what some called “diet trends” at the start of the movement are now concerned it will become lower consumer demand.

At least that’s what Rustgi fears most — that wheat, and all of the crops’ other health benefits, will be left behind in a gluten memory. But if plant breeders can find ways to reduce gluten, or separate out the “bad” from the “good” gluten, the crop stands a chance to compete in this new dynamic and feed millions globally.

“We need to find a solution where we don’t have to remove wheat from the diet,” Rustgi says.

Not All Gluten Is “Bad”

Rustgi didn’t just work alone. His team worked with colleagues at Clemson University, Washington State University and partner institutions in Chile, China and France, to develop a new genotype of wheat with built-in enzymes that break down the proteins that cause the body’s immune reaction.

“Not all wheat gluten protein is bad,” he explains. “Rather, we can keep an amount of non-immunaoenetic-gluten.”

The new wheat varieties are genetically engineered to contain two enzymes: one from barley that attacks gluten and another from the bacterium Flavobacterium meningosepticum. These enzymes, called glutenases, break down the gluten in the humane digestive tract and reduce the amount of indigestible gluten peptide by two-thirds.

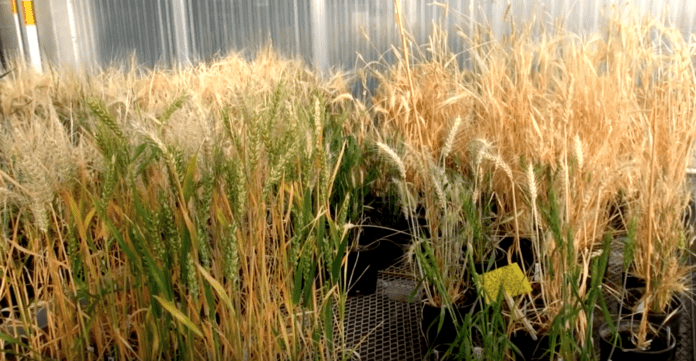

The new varieties, which are based on soft white wheat genetics, are still in the research phase and are being tested for in-field growth characteristics, as well as end-use baking properties. The lines are not ready for commercialization.

Phenotypically the new lines look exactly like their mother plants, he adds, but the technical baking properties of the reduced gluten varieties differ from their wild type counterparts.

“In the U.S., we have six different classes of wheat. The soft wheat is actually grown to make cookies and cakes. When we modified the wheat, its bread mixing properties became similar to the hard wheats that are used for bread,” Rustgi says. “Interestingly, removing those toxic proteins made the soft wheat bake like the hard wheats.”

In this phase, Rustgi says there is more work to do. While the variety exhibits 76% less gluten than traditional wheat, the goal is 90% or more gluten reduction. And until genetically engineered wheat becomes more accepted by the public and export partners, there is little opportunity to move forward.

With that in mind, he is including CRISPR and other technologies in his research for lower gluten wheat. While it will likely require an additional five years to move through the research and in-field testing process, he hopes the end result will be more widely accepted by consumers.

Another area to watch is how crop management strategies, such as the amount of nitrogen or sulfur that is applied, affect gluten levels. “If we will also do the correct management, we can significantly reduce these toxic proteins from getting into the food chain,” Rustgi says. “That could be a critical role when are creating these reduced-gluten genetic lines.”

“By packing the solution to gluten intolerance into the grain, we’re giving consumers a simpler process to accept. This means people with celiac can enjoy the foods they eat without the consequences,” he says. “We’re also reducing the danger from cross-contamination with regular wheat, as the enzymes in our wheat will break down that gluten as well.”