Ah, the good old days! Everything was better back then!

Or was it?

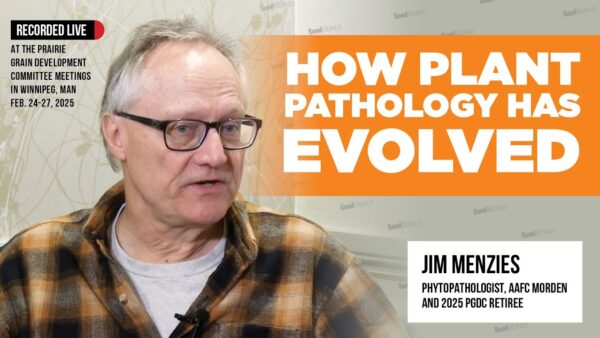

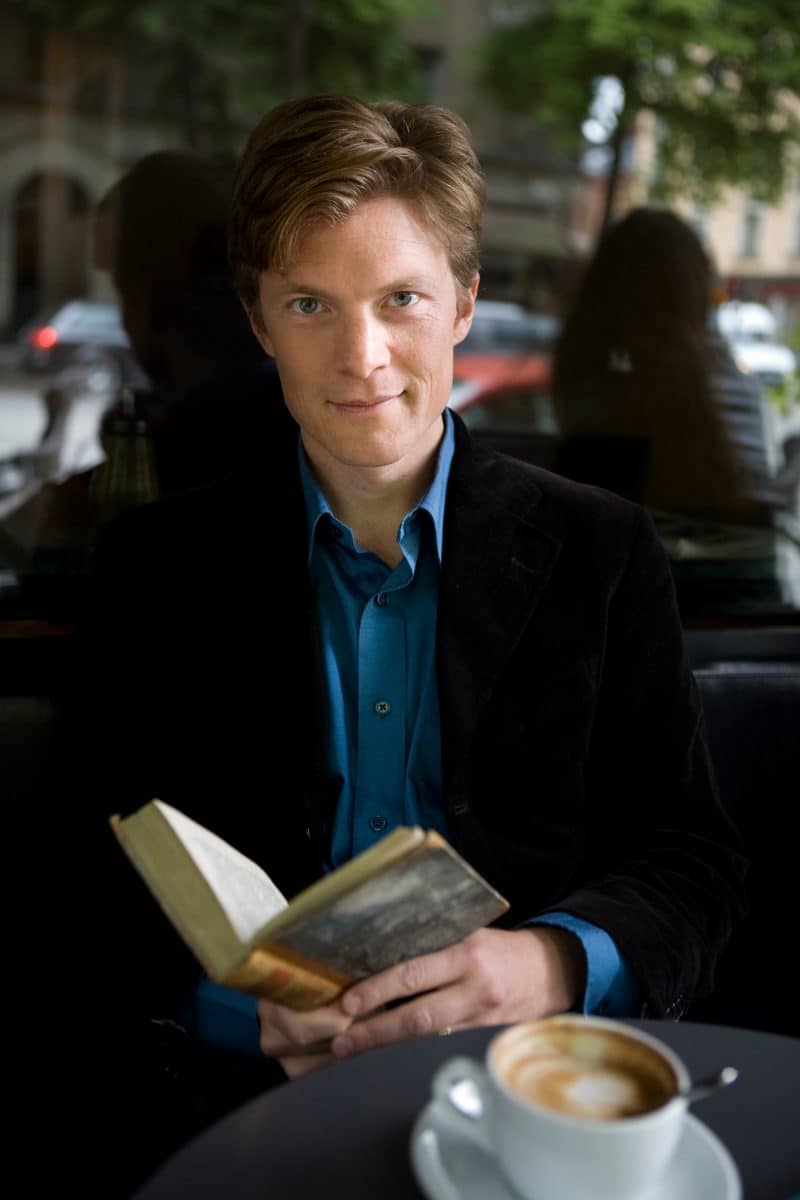

Surveys show that in many countries, a majority of the people, often up to 70 per cent of the population, suffers from the belief that “things are worse than they used to be”. This is surprising, considering that we are, overall, richer, healthier and longer-living than ever before. Swedish author Johan Norberg describes in his book, “Progress: Ten Reasons to Look Forward to the Future” the progress that we have made in the fields of food, sanitation, life expectancy, poverty, violence, the environment, literacy, freedom, equality and the conditions of childhood. Enough reason for our sister magazine European Seed to get his opinions on why we should look forward to the future.

European Seed (ES): Why did you feel it was necessary to write this book?

Johan Norberg (JN): Because we are right now experiencing the greatest social and technological progress the world has ever seen, and yet everyone seems to despair and long for some mythological good old days in the past. I wrote it because it’s dangerous to take progress for granted, because then we might not think about what it requires, and bloc avenues to further progress. Despair might even become a self-fulfilling prophecy, because people who are afraid build walls and regulations, rather than open up for further openness and innovation. Only those who believe in the future invest in it.

ES: Besides anti-innovation, there is also strong anti-globalization movement. Why are they wrong?

JN: Because globalization is the surest way to improve the world. The more people who are involved in creating knowledge, technology and business models, the greater the stock of knowledge and wealth there is, and those who benefit from that are the ones who are open to it. When walls come tumbling down and people get a greater chance to trade, travel and communicate, the more eyeballs look at our problems, and the more brains are hard at work trying to solve them.

This is why extreme poverty has been reduced by around 140,000 people every day in this era of globalization.

ES: How can we overcome such opposition?

JN: We have to explain the benefits of globalization again and again, and that is exactly what I am trying to do. To explain that every successful society on the planet has been open to trade and people, and no country has been successful without it. And even if you only care about making your own country great, you have to understand that your industry and your farmers can’t be successful without using the best ideas and inputs from around the world. Why would anyone be interested in what you produce at a higher price than your competitors?

And for those who think that protectionism and isolation would be a way of helping the disadvantaged, we have to remind them that no one has a stronger interest in decent goods and services at a cheap price, especially since the poor consume relatively more of things that are traded internationally, like food, clothes and electronics, whereas the rich spend more on say, real estate, lawyers and doctors. This means that in a country like Britain abolishing all international trade would just reduce the purchasing power of the richest tenth by 10 per cent, but of the poorest tenth by as much as 54 per cent.

ES: Globalization is not bad for the environment, but rather the opposite. How come that still so many people feel drawn to the other narrative?

JN: Yes, “poverty is the worst polluter” as Indira Gandhi put it. It’s only as countries grow richer that they can afford to improve the lives of their families and also think about their impact on nature, and we have never seen such a rapid diffusion of green technology as we have done today, thanks to freer trade. The problem is that people associate globalization with transportation, food miles, and so on, and it’s a very visual image of pollution. Why can’t we just buy everything locally? Because it would be worse. Most studies for most goods show that just around a tenth of the greenhouse gases come from the transportation of it, almost all of it comes from the production phase. So, if we can make it a little bit more environmentally friendly to produce something on the other side of the world, it might make environmental sense to buy it from there.

JN: They might think that they take back control when they have their own local standards, but in reality, it is often regulatory capture from local businesses and interests, who want to tailor those standards to keep the competition out. This is just protectionism through the backdoor. It’s important to explain to people that more open standards and international agreements is a way to open up for more competition, diversity and innovation, and this is what helps consumers and makes economies progress. And if some governments and local interests don’t listen, we have to explain that a world without this is a world where the rest of the world also tailor their own standards to their own situation and keep you and your goods and services out.

[tweetshare tweet=”People have always feared the new. It’s probably part of human nature. And this is especially so when it comes to the food we eat.” username=”germinationmag”]

ES: Countries have all kinds of reasons to diverge from the internationally agreed regulations, and with that divergence comes a stifling of free trade. How to convince countries that global alignment of their regulations benefits free trade and benefits all?

JN: They might think that they take back control when they have their own local standards, but in reality, it is often regulatory capture from local businesses and interests, who want to tailor those standards to keep the competition out. This is just protectionism through the backdoor. It’s important to explain to people that more open standards and international agreements is a way to open up for more competition, diversity and innovation, and this is what helps consumers and makes economies progress. And if some governments and local interests don’t listen, we have to explain that a world without this is a world where the rest of the world also tailor their own standards to their own situation and keep you and your goods and services out.

ES: Coming from the seed sector, I found the first chapter on food highly interesting. Famine went from being a universal phenomenon to being an exception affecting only a small fraction of the world. What else should be done to decrease hunger?

JN: The green revolution has been an extraordinary achievement. The share of chronically undernourished globally has declined from around 5 in 10 to around 1 in 10 since the 1940s, despite an increase in world population by almost 5 billion that made everyone expect us to see a massive increase in hunger. But we have to continue. We have to increase agricultural production dramatically to feed the 10 billion people by 2050. I think the green revolution has some way to go. Many poor places, especially in Africa needs more fertilizer, pesticides and efficient irrigation. But in most places we have already reached the optimum, and if we don’t want to clear the remaining forests of the world, we need better crops to increase the yield. We need plant science and we need GMOs.

ES: We are seeing a broad opposition against innovation in all kinds of sectors but most notably in the agriculture and the seed sector. Why is that?

JN: People have always feared the new. It’s probably part of human nature. And this is especially so when it comes to the food we eat. Because trying out that strange looking plant sometime in mankind’s pre-history might have killed you. Better the devil you know. The paradox is that we did experiment back then as well, but without any scientific understanding of what we were doing, which made it a hassle, and also more dangerous. Now we do know much better, but our instinctual conservatism is still there. If you add to this a common way of looking at farming, which is stuck in some outdated 19thcentury Romanticism that meets Disney, you understand why it’s always more sensitive to introduce innovation here than in say manufacturing.

ES: Recently the European Court of Justice ruled that plant breeding innovation products should be regulated in the same way as GMOs. What is your take on this decision?

JN: Well, if we had a rational, evidence-based regulatory process for GMOs, it would not matter that much, but as things are now, I think it’s a nightmare. It turns Europe into a scientific backwater as it makes it near impossible for new innovative solutions to deal with world hunger and unhealthy eating habits to see the light of day, at least for everybody but the biggest agri-businesses who might afford the regulatory costs.

It is also absurd, since the ECJ seems to say that gene editing, which makes very precise and predictable changes to a plant’s genome, is dangerous and risky, whereas exposure to radiation that results in hundreds of random changes are perfectly safe. It almost reads like a parody.

ES: Most food, feed and fiber starts with seeds. So, it seems crucial that we boost plant breeding to create higher yielding and more productive varieties. Yet we are seeing a movement towards older and less productive varieties. How can we better communicate the benefits of science?

JN: Yes, I think Douglas Adams explained it best in his attempt to understand people’s reaction to technologies: “1. Anything that is in the world when you‚Äôre born is just a natural part of the way the world works. 2. Anything that’s invented between when you‚Äôre 15 and 35 is new and exciting and you can probably get a career in it. 3. Anything invented after you‚Äôre 35 is against the natural order of things.”

And then it’s perfectly understandable that people long for what is natural, what they can recognize, rather than the strange new stuff. I find that people understand it better when you explain that we have always engaged in plant breeding, and everything that we use and eat and treasure today is the result of experiments that previous generations thought was against the natural order of things. And then we also have to provide them with specific examples of the real benefits to consumers, farmers and society.

ES: We know that organic agriculture has caused numerous fatalities (mostly through contamination with E. coli), whereas GM has caused none. What is wrong with the risk-perception of mankind?

JN: This is precisely the Douglas Adams law of technologies again! We just assume that what we already have is good, because we are used to it. It just feels better, it has nothing to do with evidence. I saw one study about how 70 per cent like organic farming, but when they were asked to define it, only 20 per cent thought that they could.

And this is exactly the problem with the precautionary principle, it is basically the idea that we should never do anything for the first time, because there might be some risk associated with it. Then we just accept much worse problems with old technologies – and you know starving is not entirely risk-free either! And this introduces an entirely arbitrary divide between old and new technologies. Very few of the technologies that we use today would have been allowed had we had some kind of precautionary principle in place when it was first used.

Where on the web: http://www.johannorberg.net/