How can the world deal with the double-edged sword that new technologies represent to the problem of food insecurity?

The Green Revolution occurred between the 1950s and 1960s and significantly increased agricultural production worldwide. Unfortunately, it was limited by many factors with a major one being major global population growth. Additionally, the intensification of agriculture was established in many areas that were in favourable regions and marginal production lands were neglected, which in some ways intensified poverty and food insecurity on those regions.

The problem of food insecurity in the world has not gone away.

What has this to do with industry consolidation and GM technology?

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, hunger is on the rise — going from 804 million people being malnourished in 2016 to 821 million people in 2017. Research is quickly moving towards genetically modified organisms (GMO), regenerative agriculture, and other proteins that are more sustainable than the current livestock we grow today.

When it comes to GMO, the technology has the potential to increase food yields that can sustain the growing world’s population. Compared to traditional breeding, GMOs are much faster to develop. It can be done with fewer resources and provide bigger and more nutritious selections of the original counterparts.

As of today, no other option is as impactful as GMO, as we try to stay ahead of pests, diseases, constant extreme weather changes and depleted resources used to grow crops while still achieving the high yields and nutrition required.

GMO has taken a hold of a large portion of our current food supply, but most people are unaware of this. The Center for Food Safety states that 75 per cent of processed foods contain GM ingredients. Genetically modified soybeans accounted for 94 per cent of cultivated soybeans in the U.S. in 2014, and Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) resistant corn now dominates farmland at 82 per cent. Still, there is fear and uncertainty surrounding GM technology.

Considering GMOs have been around since the 1980s, they are still not well accepted among consumers. The acronym GMO itself often comes across negatively in the eye of consumers, but with time and more education, GMO may become accepted by them. Perhaps if one day there are no other viable options, it will be readily welcomed. Nevertheless, scientists, policymakers and the industry should continue to put in more efforts to educate people.

However, that can be quite challenging considering the volume of information that people have access to on the internet. There is a lot of misinformation that contributes to the misunderstanding of this technology. It is difficult for regular consumers to decipher between fact and fiction, which affects their ability to make informed decisions about food and nutrition.

GMOs are also regulated differently in different countries and the definition of what is considered a GMO varies between countries. Because of this, GM products are not readily accessible by all consumers around the world. For example, in the U.S. and Canada, there is voluntary labelling of GM products but in the EU, Japan and New Zealand, GMO labelling is mandatory.

China has the largest population in the world, yet they have tightened their regulations on GMO labelling and have no clear method of how to implement them. Furthermore, conventional breeding with marker-assisted selection is classified differently, with some claiming since it involves humans directly modifying the genome, it is GM technology. Others argue otherwise.

Maybe in the near future, when the effects of climate change become even more serious and food shortage is imminent, governments, scientists and industries around the world will come to terms with all the facts and create interchangeable policies and regulations that can provide access to GM foods for all consumers.

An interesting point to mention is that malnutrition and obesity coexist in many countries of the world. Food shortage can lead to this global obesity epidemic because of highly processed and non-nutritive foods available. Fresh foods are generally more expensive, and in lower income families, the less expensive foods with high calories and low nutrition are often the only options.

It may be a good thing that groups such as Monsanto, Syngenta and other pioneering research companies are putting their resources into genetically modifying foods in order to enhance its features that will help with yield and nutrition to alleviate the food insecurity issue. If these types of companies do not take the reins, probably no one else would, and we would not be as far ahead as we are now in terms of addressing the food insecurity problem.

However, the opposite has been said of consolidation within the industry; that what we are doing is monopolizing the world’s food supply. This perception only intensifies a lot of anti-GMO sentiment that exists among consumers.

Regardless, scientists can and must learn to communicate better, in layman’s terms, to regular consumers. Additionally, government can provide more resources on the topics of food and nutrition (Canada’s new food guide puts an emphasis on plant-based protein, for example), and the industry can be even more transparent about their research and products.

If we tackle the future collectively and proactively, we can do a lot to improve and perhaps one day solve the problem of food insecurity.

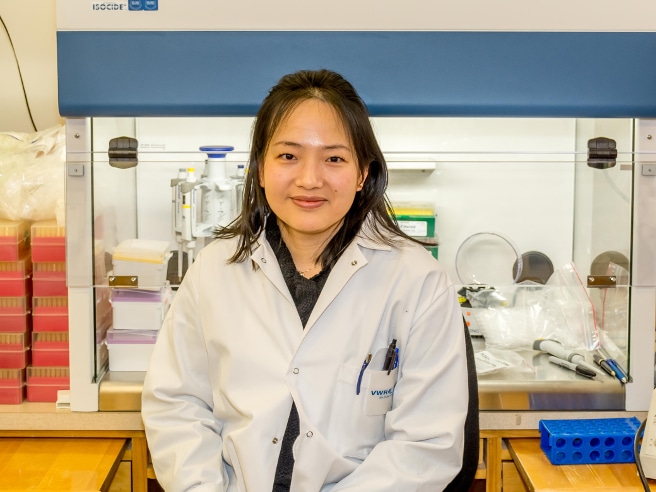

—Le Hoa Tan is a research assistant in Dr. Bahram Samanfar’s soybean functional genomics lab working in collaboration with Dr. Elroy Cober on soybean breeding at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Ottawa. This article was written with assistance from Bahram Samanfar and Elroy Cober.