The question is unanswered, but one life science company had the foresight to corral the right licensing agreements from both inventing parties.

Who owns CRISPR? That’s a billion-dollar question, literally. Those involved in life sciences are closely watching the developments. In 2012, Jennifer Doudna, a biochemist at the University of California, Berkeley, published the first paper on the enzyme in Science, and in May of that year, Berkeley filed a patent application for the basic CRISPR technology.

In December of 2012, the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT filed an application but paid an extra fee for an expedited route to patent CRISPR in eukaryotic cells (those in plants, animals and people). In 2017, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office granted Feng Zhang and the Broad team the patent for using CRISPRCas9 to edit DNA in mammals. Doudna’s team appealed the decision but the USPTO’s patent trial and appeal board decided in favour of the Broad. Their reason: the two teams’ discoveries didn’t overlap and that the Broad’s patents covered a truly separate innovation. Again the Berkeley team appealed that decision, and it went before federal judges in Washington, D.C., April 30.

At the time of print, a decision had not been made but it’s expected in the 2018 calendar year. Earlier this year (2018), the USPTO awarded UC-Berkeley its first CRISPR-related patent; it focuses on using CRISPR-Cas9 to edit single-stranded RNA (not DNA). A second patent came shortly after, which centres on using the standard CRISPR-Cas9 system to edit regions specifically 10-15 base pairs long.

To date, there are more than 60 CRISPR-related patents in the United States that have been awarded to inventors at 18 different organizations. But globally, more than 18,000 individual patent applications and granted patents, according to Jack Hopwood, a consultant with Clarivate Analytics. According to one report, the market for this gene-editing technology is expected to rise from $3.19 billion in 2017 to $6.28 billion by 2022.

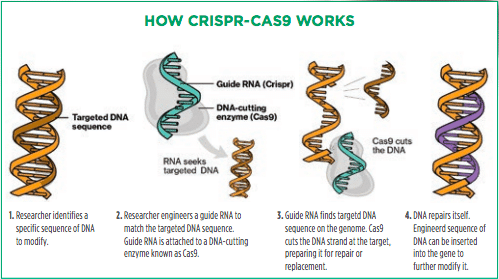

Chris Donegan, cofounder of Invention Capital Associates, co-wrote: “The power of CRISPR is extraordinary: it has already been used to reverse muscular dystrophy in living mammals and as a live editing tool for our genome, it has the potential to be the most powerful discover in history.”

As far as the seed industry goes, Pioneer (turned DowDuPont, turned Corteva Agriscience) had the foresight to corral licenses to the intellectual property from both the UC-Berkeley and the Broad teams. The company is now the single biggest owner of CRISPR patents and applications globally with 514, or 12 percent of the total. The company uses CRISPR to develop corn and soybean crops that repel insects without chemical pesticides and that tolerate herbicides for easier control.

[tweetshare tweet=”The power of CRISPR is extraordinary: it has the potential to be the most powerful discover in history.” username=”germinationmag”]

According to a Bloomberg article, since the end of 2016, about 100 new inventions are being disclosed every month.

“The market concerns I have heard is that the CRISPR patent landscape is very large, very confusing and difficult to navigate,” says Kristin Neuman, executive director for Biotechnology Licensing at MPEG LA, a group that’s trying to develop a patent pool. Neuman says it’s hard for people to figure out what rights they need to license and who they need to license.

This patent pool would serve as a one-stop shop for anyone wanting to license the basic technology, no matter which enzyme variant is used. Billions of dollars in licensing agreements is at stake. Either way the court goes, the companies licensing from the losing party will have to seek new license agreements from the party that prevails. This could impact company stocks and time to market with products in development.