Despite fears about doing so, scientists can talk openly about the reality of global warming. There are some clever ways to help you do so.

It’s hard to believe that in the modern age, people can still be afraid of talking science.

For a lot of researchers, that fear comes from discussing climate change with the public, despite the majority scientific consensus that greenhouse gas emissions resulting from human activity are causing changes in the climate.

“I feel like I need to be careful when I talk about climate change. It speaks to a lot of things right now,” says Molly Cadle-Davidson, chief scientific officer for ABM based in Geneva, New York.

Cadle-Davidson, an expert in the field of genetics and well-versed in the application of genomics and next-generation sequencing techniques for trait-based microbial research and development, says she’s often faced with a problem all too common among researchers — how to talk about human-caused climate change without creating controversy, and whether to talk about it at all.

“If the audience is unknown to me I will ask conference organizers if I can bring up the issue of climate change. There are people who just don’t want to discuss it or hear it talked about, and as a scientist, that can pose a huge challenge. How do you communicate the message if you can’t talk about something so important?”

A study co-authored by University of Montreal researchers suggests that while 79 per cent of Canadians accept the reality of climate change, 39 per cent do not believe it is caused by humans.

A majority of Canadians, though, support policy changes aimed at curbing global warming. Sixty-six per cent support a cap and trade system, according to the study. Millennials (ages 18-34) are even more adamant, with more than 70 per cent saying that doing more to address climate change is important, according to an Environics Research Group survey.

While those numbers are encouraging, rejection of climate change data is still a powerful force, even in agriculture, notes Claudia Wagner-Riddle, professor in the School of Environmental Sciences at the University of Guelph in Ontario. She studies mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions and what farmers can do to reduce production of greenhouse gases on-farm.

“The farming community is becoming more convinced in regard to climate change, but there are still views out there along the lines of, ‘Yes, the climate is changing, but there’s no good proof of what is causing it.’ That’s unfortunate, because we have plenty of evidence that it is caused by greenhouse gas emissions. Problem is, the science is difficult to convey in a simple way.”

Why the Denial?

Climate change rejection/denial is prevalent on social media, and according to Wagner-Riddle, a major hurdle for scientists to try and get over.

“There’s a lot of disinformation being spread, and a notion that scientists are somehow biased because they get research money to study climate change. It really is ludicrous — a scientist by definition is skeptical, and if someone could prove human-caused climate change isn’t happening, that would be done in a heartbeat,” she says.

The evidence continues to pile up showing human-caused climate change is real and having dire consequences for the globe. Thirteen federal U.S. agencies recently released a comprehensive report concluding that, based on extensive evidence, it is “extremely likely that human activities, especially emissions of greenhouse gases, are the dominant cause of the observed warming since the mid-20th century. For the warming over the last century, there is no convincing alternative explanation supported by the extent of the observational evidence.”

The U.S. Global Change Research Program Climate Science Special Report, approved for release by the White House itself (despite President Donald Trump’s continued doubts about the reality of climate change), goes on to state that, “In addition to warming, many other aspects of global climate are changing, primarily in response to human activities. Thousands of studies conducted by researchers around the world have documented changes in surface, atmospheric, and oceanic temperatures; melting glaciers; diminishing snow cover; shrinking sea ice; rising sea levels; ocean acidification; and increasing atmospheric water vapor.”

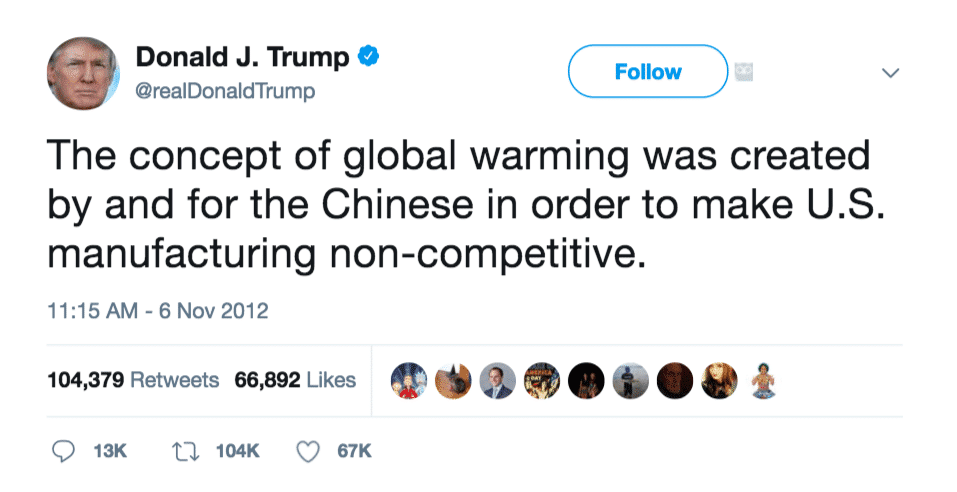

Despite the overwhelming evidence for human-caused climate change and massive support for measures to curtail it, efforts to undermine those messages are prominent. That disinformation is so effective due, in part, to the American political climate. Trump famously tweeted in 2012 that climate change is a hoax perpetrated by the Chinese to steal American jobs. Combine that with a lack of efficiencies in science education and the general public’s mistrust of science, and you have a recipe for climate change skepticism.

“It used to be that scientists were trusted. Now people take a scientist’s results with a bit more caution,” Cadle-Davidson says.

That’s due to a number of factors, a big driver being a perception that scientific research is funded by corporate entities with nefarious intentions.

“Big corporations are seen as pushing science to make a buck, and that’s also damaged what we do, because the public sees that corporations are out to make money. I see this over and over again in the area of seed-applied biologicals. If you show people your data, the question is, ‘Yeah, but who paid for that research? What’s your motivation? Someone paid for you to do that, therefore you have a bias in the data.'”

And why, she asks, wouldn’t the public be skeptical?

“Big Tobacco paid for research on smoking and its impact on human health, and it hid the negative results for years. Obviously, that’s different than climate change, but the point is the public feels like they’ve been burned by big companies, and that has spilled over into the climate change arena.”

Noted psychiatrist and historian Robert Jay Lifton recently published The Climate Swerve: Reflections on Mind, Hope, and Survival, in which he argues that our society is going through a time of increased recognition of the reality of human-caused climate change, a psychological shift he refers to as a “swerve.”

A swerve, Lifton says, is driven by a combination of evidence, economics, and ethics. In a recent interview with Diane Toomey of Yale University’s online magazine Yale Environment 360, Lifton says denial of climate is a kind of natural progression that the human mind goes through on its journey to accepting something a problem as real. Accepting human-caused climate change as real comes with such profound implications for humanity, that he says it’s natural for humans to reject it at first.

“With climate images, when they’re fragmentary, we may have an image of a storm here, of sea rise here, a little bit of flooding there, the drought. But when that becomes a formed image involving global warming and climate change, we take in the idea of carbon emissions leading to human effects on climate change and endangering us. And in that same narrative, there can be mitigating actions to limit climate change,” he tells Toomey.

The good news, he goes on to say, is that climate change denial will eventually run its course.

“[Climate change deniers] have to know in some part of their minds, that climate change is quite real and dangerous. It’s becoming, I’ll argue, more and more difficult to take the stand of climate rejection, because there is so much evidence of climate change and so much appropriate fear about its consequences. …It won’t go away. The climate rejecters are fighting a losing battle.”

That said, Wagner-Riddle notes the shift won’t happen overnight, and the fact climate change science can be hard to convey to people in a simple way is a major challenge for scientists to tackle.

“With the ozone layer, which used to be the topic of the day, people didn’t have much trouble accepting that refrigerants used in fridges and air conditioners caused the ozone hole. That is a straight line — you have these products that end up in the stratosphere and destroy ozone,” she says.

“With climate change, there’s many factors at play — greenhouse gases produced by humans, solar cycles, changes in the earth’s orbit, volcano eruptions and so on. It’s harder for our brains to process.”

There are, however, strategies to be employed in making the conversation easier.

What You Can Do

“Simply telling farmers, for example, that if they do a certain thing the nitrous oxide emissions from their soils will be reduced, that message doesn’t quite get through. Farmers are businesspeople, and businesspeople are naturally interested in how the actions they take will benefit them and their bottom line,” Wagner-Riddle says.

It’s critical to translate the scientific language in a way that shows growers and others that reducing greenhouse gas emissions will benefit them directly.

“Greenhouse gas reduction is related to better use of nutrients and seed — that needs to become the message. Using better inputs can earn the farmer more money, and makes it more difficult for them to continue practices that don’t necessarily do that.”

Cadle-Davidson manages to talk in different terms that don’t necessarily mention climate change directly, but still get the point across.

“Depending where I am, I might just refer to suboptimal environmental conditions, developing microbial products for extreme environmental conditions, that kind of thing. Another concept is changing land use, and how we can adapt to warming by growing crops in places we never have before. There’s lots of opportunities to talk about those concepts, and that’s where I find the safe spot.”

Another effective strategy, Cadle-Davidson says, is to simply continue doing good science.

“I always felt that engaging in good science was my best defense. The occasional bit of lazy science is enough to call an entire field into question because a single instance will get a lot of press as the counter example. Vocal climate change deniers can easily wash out the voices of scientists owing to the differences in argumentation styles mentioned earlier,” she adds.

“People can yell as loud as they want, but if scientists can operate on a more subtle level, that could be fine. Scientists don’t need fame. The hope is that we can guide policy and be a force for positive change over time.”